A very good visual correlation between the yearly percentage change in the consumer price index (CPI) and the yearly percentage change in the price of oil seems to provide support to the popular thinking that future changes in price inflation in the US are likely to be set by the yearly growth rate in the price of oil (see chart).

But is it valid to suggest that a price of an important input such as oil is a key determinant of the prices of goods and services?

Now producers of goods and services set asking prices. It is also true that producers whilst setting prices take into account various production costs including the cost of energy.

Whether the asking price set by producers is going to be realised in the market place hinges on consumers’ acceptance of the price set. Consumers dictate whether the price set by producers is “right”.

On this Mises wrote,

The consumers patronize those shops in which they can buy what they want at the cheapest price. Their buying and their abstention from buying decides who should own and run the plants and the farms. They determine precisely what should be produced, in what quality, and in what quantities.[1]

If consumers don’t have the money to support the prices asked by producers then the prices asked cannot be realised.

What is a price? It is the rate of exchange between goods established in a transaction. The price, or the rate of exchange of one good in terms of another, is the amount of the other good divided by the amount of the first good.

In a money economy, price will be the amount of money divided by the first good. A price is the sum of money paid for a unit of a good.

If the stock of money rises whilst all other things remain intact obviously this must lead to more money being spent on the unchanged stock of goods– an increase in the average price of goods. (The term average is used here in conceptual form. We are well aware that such an average cannot be computed).

If the price of oil goes up and if people continue to use the same amount of oil as before then this means that people are now forced to allocate more money for oil. If people’s money stock remains unchanged then this means that less money is available for other goods and services, all other things being equal. This of course implies that the average price of other goods and services must come off.

Note that the overall money spent on goods does not change – only the composition of spending has altered here, with more on oil and less on other goods. Hence, the average price of goods or money per unit of good remains unchanged.

From this we can infer that the rate of increase in the prices of goods and services in general is going to be constrained by the rate of growth of money supply, all other things being equal, and not by the rate of growth of the price of oil. We suggest that it is not possible for rises in the price of oil to set in motion a general increase in the prices of goods and services without corresponding support from money supply.

One could, however, argue that a rise in the price of oil may result in an increase in the growth rate of money supply i.e. the increase in the price of oil will be monetized. This in turn should provide support for a general rise in prices on account of the increase in the price of oil.

Even if this were to be the case, because of a lengthy time lag from changes in money to price inflation in the short run this would have almost no effect on the growth momentum of the CPI.

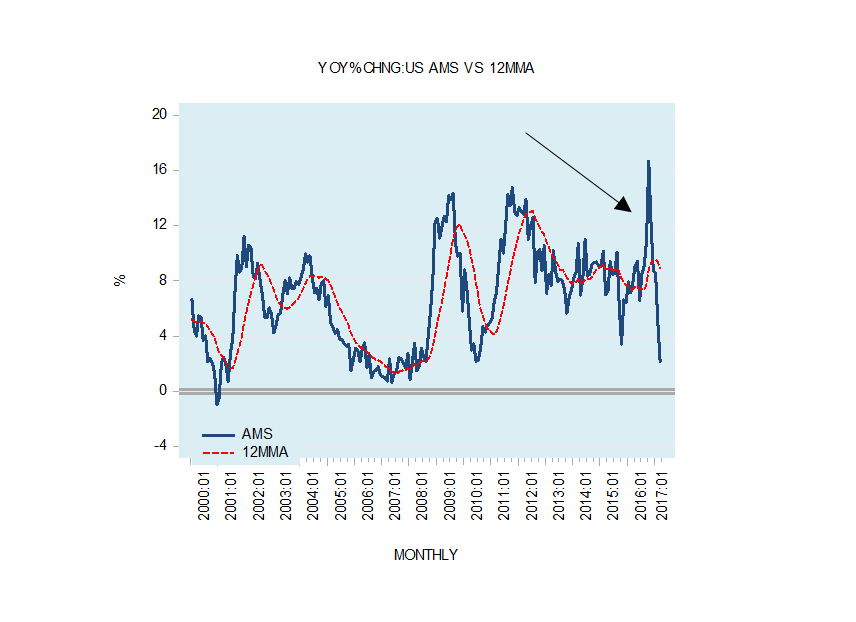

After peaking at 13.1% in July 2012 the 12-mma of the yearly growth rate of our monetary measure AMS has been in a visible downtrend for the US, closing at 8.9% by March this year. Based on this we can suggest that the growth momentum of prices of goods and services is likely to follow a downtrend in the months ahead.

Note that our conclusion regarding the future growth rate of prices of goods and services is based on core principles rather than simply relying on statistical correlation – the technique used and regarded as so important by many economic analysts. We have shown that the core driver of general increases in prices of goods and services is money supply (AMS) growth that in turn is driven by central and commercial bank money creation, not the price of oil.

[1] Ludwig von Mises, Human Action, Contemporary Books third edition p 270.

Thank you for the article, Dr. Shostak. Would you elaborate on how the subjective theory of value layers in to this discussion?