On this website Toby Baxendale presented his plan for monetary reform. He offered a reward of £1000 for anyone who can provide a logical reason why it won’t work; naturally this provoked a lot of discussion. In my opinion Toby’s plan has a major problem, and I discussed this with Toby and the Cobden Centre team over email. Toby doesn’t agree that I’ve found a major flaw in his plan. However, we both think that the debate should be opened up. This article summarises the discussion we’ve had so far.

The Cobden Centre recognize the need for monetary reform, as do I. Reform of money and banking is urgently needed to avert future economic crises. I also agree that Austrian Economics provides a sound understanding of the issues. However, I doubt that the Baxendale plan could be successful. In my opinion if the plan were enacted there would be a burst of price inflation immediately after. The reasons for my concern come from simple economic theory.

What Task Does Money Perform?

Ludwig von Mises described the job of money as follows:

“What is called storing money is a way of using wealth. The uncertainty of the future makes it seem advisable to hold a larger or smaller part of one’s possessions in a form that will facilitate a change from one way of using wealth to another, or transition from the ownership of one good to that of another, in order to preserve the opportunity of being able without difficulty to satisfy urgent demands that may possibly arise in the future for goods that have to be obtained by way of exchange. So long as the market has not reached a stage of development in which all, or at least certain, economic goods can be sold (that is, turned into money) at any time under conditions that are not too unfavourable, this aim can be achieved only by holding a stock of money of a suitable size.” [1]

What Tasks Do Bank Accounts Perform and How Do They Work?

The economics of banking is important here because bank accounts are pivotal to the Baxendale plan. A balance in a bank account that provides on-demand payments and transfers provides services that are similar to those of note and coin money. Again, Mises gives a good description of the situation:

“The cash balance held by an individual need by no means consist entirely of money. If secure claims to money, payable on demand are employed commercially as substitutes for money, being tendered and accepted in place of money, the individuals’ store of money can be entirely or partly replaced by a corresponding store of the substitutes.” [2]

In Mises’ terminology notes and coins are money-in-the-narrower-sense. A bank balance in an on-demand account is a money-substitute. Money-in-the-broader-sense is the sum of money-in-the-narrower-sense and money-substitutes such as bank account balances.

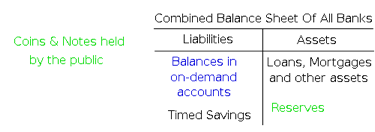

A balance in a bank account is a debt that the bank owes to the account holder. As Toby writes in his article “… your bank-statement is a mere IOU”. Banks invest the money deposited into accounts, often in loans and mortgages. Banks keep only a small amount of “reserves” of money-in-the-narrower-sense. The diagram below shows the situation:

Entries marked in blue on the diagram are money-substitutes. Entries marked in green are money-in-the-narrower-sense.

The Baxendale Plan

Toby Baxendale’s plan is based on a similar plan by Jesús Huerta de Soto, an economist of the Austrian School from Spain. The essence of the Baxendale plan is that it makes all money-substitutes into money-in-the-narrower-sense. Lorry loads of notes are shipped to banks to make this happen. After the plan is enacted a bank statement that says £550 means that the bank is holding a corresponding £550 in notes and coins. The legal relationship between the customer and the bank is altered, after the plan the customer is no longer lending to the bank, instead the bank is acting as custodian of the customer’s cash. The bank becomes a “money warehouse” [3]. Since the balances of on-demand accounts become possessions of the customer, not debts, they no longer appear on the bank’s balance sheet. So, after the plan the banks will have an asset surplus. Rather than allow the banks to profit from this Toby intends to use these assets to pay off the national debt. Specifically, Toby proposes that the asset surplus be removed and put into a mutual body to pay off the national debt.

Bank Services and Interest Payments

A balance in an on-demand account isn’t just a money-substitute, it entitles the account holder to extra services from the bank. In Britain banking services such as payments and transfers are free, some on-demand accounts also pay interest. A balance in an on-demand account provides the holder with two things. Firstly, it provides a reserve of wealth that may easily be exchanged, just as notes and coins do. Secondly, it provides access to banking services and in some cases interest payments. Toby plan is that the banks’ assets will be used to pay off the national debt. That should lead us to ask: what role are those assets currently employed in? The answer is that they provide the income that is used to provide free banking services and interest.

It’s the income from a bank’s assets that funds free services and interest-bearing accounts. If the Baxendale plan were enacted then this stream of income would dry up. Banks would have to start charging fees for services and stop paying interest on balances in on-demand accounts. It’s difficult to estimate what the effect of this change would be. Some people would be indifferent to the change, those who use few banking services and don’t qualify for interest-bearing accounts, for example. It’s doubtful though that every account holder will fall into this category — if they did then these extra services would never have been commercial successes in the first place. Many other account holders will be sensitive to this change. I myself have been a user of interest-bearing on-demand accounts for more than a decade; I’ve always used a portion of my balance as savings.

Let’s suppose the plan is enacted and interest payments cease. Those savers like me who hold balances in on-demand accounts in order to receive interest will have to change our ways. The change will be permanent: the type of saver who once held a large balance in an on-demand account as an investment can no longer exist. Consequently, there will be a fall in the demand for these accounts’ balances when the plan is enacted. This is a fall in the demand for money. The savers in question will invest elsewhere, in interest-bearing bonds for example. Banks today offer notice accounts where the account holder must give a few weeks notice before they can withdraw. The Baxendale plan doesn’t extend to timed savings, so these accounts will operate as before; they are the obvious alternative to on-demand accounts.

Higher charges for banking services will also have widespread consequences. Businesses and individuals will have an incentive to avoid using banks for payments and transfers. Alternative methods of payment will become more attractive. Businesses will be more likely to use debt agreements and reciprocal cancellation. Suppose two wholesale companies A and B regularly trade with each other. Before the plan they make payments using bank services. After the plan they decide this method is too expensive, so they each keep a record of the debt that is owed to them by the other. Then at a regular interval they settle the net debt using money or bank transfer [4]. This will also cause a reduction in the demand for money.

The purchases of alternative investments will trigger what is called an injection effect. The type of saver I mention above will withdraw a part of his or her balance and put it into other investments. That extra demand will raise the price of such investments. The sellers of these investment products will receive that money and spend it themselves causing further price rises elsewhere. The sellers of these investments are not required to store the money they receive, they can spend it on investment projects. In time the money will spread through a large swath of the economy and price inflation will result. It’s a very similar situation to an injection of money by the central bank. These price rises will impair the planning and economic calculations of all individuals and businesses.

To recap, my opinion is that the Baxendale Plan would lead to damaging price inflation. By removing the extra services that bank accounts provide the plan will cause a fall in demand for money. If the stock of money remains the same while the demand for it diminishes then the value of each unit of money will fall.

Toby Baxendale’s Responses

Toby doesn’t agree with my criticism, we discussed this by email. Toby gave four counter-arguments:

Bank Services

Toby suggested that after the plan banks will use free services and possibly interest payments to attract customers. Toby wrote:

“Banks should charge for services rendered, why not? Maybe they will choose to subsidise the custodianship of cash storage. I sell fish for a living and to get hotels and restaurants to buy all of our fish species we sell, we have to discount the fastest moving lines, for example the salmon, and sell for virtually nothing. We are happy to do this as we work our margin in on the less important lines to our customers. Tesco sell cans of beans at £0.07p. This can not be even covering direct costs, but it gets people to walk into their store to buy other things that they make a full and sustainable margin on.”

This is called “loss leading”, a business offers a product or service at a loss in order to attract customers and build up a relationship with them. This hopefully gives the business an opportunity to sell them other products and services that are profitable. I agree that banks are likely to do this.

But, on-demand accounts attract customers to use other banking services now under the existing banking laws. What we should examine is the change: how would things change if the Baxendale plan were implemented? The situation at present is that a bank gains in two ways from offering on-demand accounts. Firstly, the bank can lend out the funds it receives from account holders, secondly, the account services can be used to attract customers towards other services. If the plan were enacted then afterwards only the latter incentive would apply. So, I think that if the plan were enacted then the provision of free banking services would decline, all other things being equal.

The Scale of the Problem

In Toby’s opinion the size of the effect I’ve described here would be small. If the total sum of balances in interest-bearing on-demand accounts is small then the cessation of interest would not have a great effect on the wider economy. Toby found some statistics on this from the Bank of England [5], these show that in March there was £386 billion in on-demand accounts that pay interest. As discussed above quite a large proportion of that amount would remain in on-demand accounts after the plan is enacted, though it’s impossible to accurately predict the proportion. However, I think it’s still useful to compare this figure to the stock of money-in-the-broader-sense. Anthony Evans and Toby Baxendale have made a measure of the UK money stock that’s consistent with the concepts of Austrian Economics [6]. By this measure the money stock is presently about £1 trillion. So, interest-bearing balances make up approximately a third of the total. The Bank of England use a different measure – “M4” – which is based on different principles. According to that measure the money stock is about £2.2 trillion. I’ll concede that if the arguments put forward by Austrian economists against the M4 metric are wrong then I’m wrong about interest-bearing accounts. But, I think the arguments make by Frank Shostak [7] against the M metrics are persuasive.

However, interest payments are only one part of the issue, the cost of banking services is the other. If the banks were to significantly raise the fees for their services then the demand for balances in their accounts would fall. This depends, to some extent, on how the banks decide to charge. If the banks were to charge a monthly storage fee proportional to the account balance then that would be akin to a negative interest rate. That would be a strong incentive not to hold a large balance, but other charging schemes would have a similar albeit lesser effect. There are several historical precedents for this, Irving Fisher wrote about some of those in his booklet “Stamp Scrip” [8]. Fisher thought that reducing “hoarding” of money could be economically beneficial, I disagree. But, he provides evidence that charging for storage of money reduces the amount of it that people hold.

Price Deflation Afterwards

Toby writes:

“With a fixed money supply, the ongoing productivity gains by the entrepreneurs means that more goods will be offered for sale at better prices, this means the purchasing power of money has gone up. As this is the only way that we have economic progress with a fixed money supply, people will be more fixated on what their money buys rather than what the numerical value is supposedly going up by.”

In the long run Toby is correct, but, in the short run the purchasing power of money is affected by the demand for money. Steady price deflation could occur in the long run after the short term effects I’ve discussed here have played out. But, the stumbling block is the period directly after the plan is enacted. If I’m right and price inflation occurs then the government may call a halt to the plan and reintroduce the current banking system.

Effect of the Plan on Production

Toby writes:

“I concur with you that price realignments will take place as people adjust to the brave new world. This is wholly right and good, as what consumers want will be more aligned with what producers produce. What producers produce will correspond more closely with what savers want to buy when they spend their money. Only bubble based activity will be deprived of credit.”

Here Toby is referring to the Austrian Theory of the Business Cycle. That theory indicates that if the quantity of money and the demand for money remain stable then unsustainable bubbles become much less likely to form. But, like the price deflation argument this is a long term theory. It can’t tell us what will happen while the demand for money is settling down from the initial disturbances caused by the implementation of the plan.

Further Discussion

I’m sure lots of people will have opinions about this, and there are many more questions that remain to be explored. I think it’s likely that there is no way of transitioning to a better monetary regime without disturbances. However, we should endeavour to predict what disturbances may occur and plan for them. For now we can continue the discussion in the comments thread below.

References

[1] Ludvig Von Mises “The Theory of Money and Credit” Liberty Fund Edition, p.170. [2] ibid, p.154. [3] Murray Rothbard “The Case Against the Fed”, p.34. [4] Ludvig Von Mises “The Theory of Money and Credit”, p.314-315 describes cancellation in more detail. [5] Bank of England “Monetary & Financial Statistics May 2010” table A6.1 column BF96 p. 52. [6] Anthony J. Evans & Toby Baxendale “The monetary contraction of 2008/09: Assessing UK money supply measures in light of the financial crisis” [7] Frank Shostak “The Mystery of the Money Supply Definition” The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics vol.3, no.4 (Winter 2000). [8] Irving Fisher “Stamp Scrip” this booklet is no longer in print. It is available here.

Thanks for this well-laid criticism. Here are a few thoughts siding with Toby:

Would the demand for money change, and would price inflation (or other price changes) ensue? Yes. I think the main point is that a change in the demand for money is unavoidable in any free market monetary reform.

The main destabilizing interventions on the market for money are the legal tender laws, lender of last resort and public deposit insurance. Austrian economists of all varieties would agree that these interventions should be seriously curtailed, if not totally suppressed.

Any money backed by the power of government is bound to be more easily marketable than without this backing, other things equal. Menger states this clearly in his principles: “The sanction of the state gives a particular good the attribute of being a universal substitute in exchange, and although the state is not responsible for the existence of the money-character of the good, it is responsible for a significant improvement of its money-character.”

Depriving a paricular good from the sanction of the state will therefore alter the demand for it. QED

This means that the consequences described by Robert Thorpe can be expected to occur in virtually all monetary / banking reforms. In my view, this would be the case for Keving Dowd’s free-market money “button-pushing” reform, and even for a remotely free-market reform such as John Kay’s narrow banking proposal. The question is whether the sanction of the state ought to be removed or not, in spite of these disturbances.

Robert Thorpe writes: “price inflation will result. It’s a very similar situation to an injection of money by the central bank.” I’m not quite sure. With our present institutions, the causal chain is C.B. printing causes bank credit expansion causes malinvestment. The market is driven away from consumer preferences by distorted signals. In the case of a monetary reform, the causal chain would be interruption of state intervention causes change in the demand for money causes price changes causes adaptation of the structure of production. Thus, the market would be allowed to adapt to consumer preferences. I guess the point here is that not all price changes are “destabilizing”.

For those who didn’t guess from the previous thread, I am Rob Thorpe.

> I think the main point is that a change in the demand for money is

> unavoidable in any free market monetary reform.

I agree. But we can do something about the magnitude of that disturbance.

> The main destabilizing interventions on the market for money are

> the legal tender laws, lender of last resort and public deposit

> insurance. Austrian economists of all varieties would agree that

> these interventions should be seriously curtailed, if not totally

> suppressed.

Yes, I’d add to that some tax laws.

> This means that the consequences described by Robert Thorpe can be

> expected to occur in virtually all monetary / banking reforms. In

> my view, this would be the case for Keving Dowd’s free-market money

> “button-pushing” reform, and even for a remotely free-market reform

> such as John Kay’s narrow banking proposal. The question is whether

> the sanction of the state ought to be removed or not, in spite of

> these disturbances.

Yes and No. Many of the other plans for monetary reform have the problem that they entail a large disturbance at the start. I could have critiqued many of them on that point. I know that in the long-term this may be a minor problem. My concern though is how do we get to the long term?

It’s not a trivial question. The Peel act caused major disturbances when it was initiated and likely exacerbated the Irish famine. If possible we don’t want that to happen again.

I realise that we can be overcautious in what we suggest. But, in my view some caution is needed. The transition could never be perfect, but we have to work out how to do it reasonably well.

> In the case of a monetary reform, the causal chain would

> be interruption of state intervention causes change in the demand

> for money causes price changes causes adaptation of the structure

> of production. Thus, the market would be allowed to adapt to

> consumer preferences. I guess the point here is that not all price

> changes are “destabilizing”.

We all make economic decisions in a particular local environment. That can be elided from simple discussions of ABCT. In those simple discussions the monetary injection reduces the interest rate in a way that’s not consistent with the amount of real savings. The longer and more precise theory is that this effect is distributed. It doesn’t just happen in the centralised market for interest. It happens all across the economy wherever calculation is being done.

The post-war German economic miracle did start with a major monetary disturbance. The article below mentions a 93 percent contraction in the money supply! Yet this did not prevent a remarkable economic growth thereafter (arguably attributable to many other factors).

http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/GermanEconomicMiracle.html

As an aside, I wish I could learn more about the Peel Act’s effect on the Irish famine. Where can I find some literature on the subject? Thanks.

> The post-war German economic miracle did start with a major

> monetary disturbance. The article below mentions a 93 percent

> contraction in the money supply! Yet this did not prevent a

> remarkable economic growth thereafter (arguably attributable to

> many other factors).

But, how would something like that play in the present world? After WWII Germans could expect a period of upset and hardships. What we’re talking about here is something quite different, we’re talking about

> As an aside, I wish I could learn more about the Peel Act’s

> effect on the Irish famine. Where can I find some literature

> on the subject? Thanks.

I don’t really know about it myself. I remember reading it somewhere, but I don’t remember where. So, I won’t push that point too far.

Thank you for your comments Gu Si Fang. I agree with them all!

I have also raised some difficulties with Toby’s plan – not least relating to banks’ non-sterling assets, to the treatment of bank capial and to the need to make the new fully-backed money conveniently transferrable.

I also agree that the banks should now charge to recoup the costs of the new warehousing services, though – despite the illogicality of the current situation – this may be wholly offset by obviating their existing need to PAY interest on what are suppposed to be demand accounts – i.e. a payout one way becomes a cost incurred another, from the banks’ perspective.

I am even more uncertain of your other argument since, to the extent that I wish to earn interest on my surplus means, I must henceforth exchange my money for a suitable asset – but this does not imply the creation of any extra aggregate demand being expressed for these (as a class, as opposed to specifically) since, as you point out, the banks already use my demand liability for that express purpose!

Equilibration will soon occur!

Thank you Sean

You get down to the detail here and that must be the next stage of this debate that has had 450 comments and sub comments to it.

> need to make the new fully-backed money conveniently transferrable.

The whole thing could be done with computer databases rather than notes. I think that would be much more feasible.

> I also agree that the banks should now charge to recoup the costs of

> the new warehousing services, though – despite the illogicality of

> the current situation – this may be wholly offset by obviating their

> existing need to PAY interest on what are suppposed to be demand

> accounts – i.e. a payout one way becomes a cost incurred another,

> from the banks’ perspective.

I don’t know what part of the current system you are criticizing as illogical.

But, I don’t think you’re right. Certainly banks don’t have to pay interest after the reform. That creates a saving that could fund services.

However, the only reason for subsidizing 100% reserve on-demand accounts would be as a loss leader. That is, they would do it so people would invest more in fixed-term or timed assets than they do. If people did invest more in timed assets then the price inflation problem I mention would occur.

On the other hand if people didn’t generally move to investing in timed assets then banks would stop the loss leading. If they stopped the loss leading then they would have to start charging fees for account services. That would drive a move away from holding money from the other side.

> I am even more uncertain of your other argument since, to the

> extent that I wish to earn interest on my surplus means, I must

> henceforth exchange my money for a suitable asset – but this does

> not imply the creation of any extra aggregate demand being

> expressed for these (as a class, as opposed to specifically) since,

> as you point out, the banks already use my demand liability for

> that express purpose!

Remember the national debt repayment mutuals. After the plan the assets of the banks that backed on-demand accounts are put into those.

Because of the principle of substitution we can talk about a demand for “either A or B”. Using this we can consider the demand for savings that is indifferent to the exact form. Suppose X is the demand for interest bearing on-demand accounts or timed savings. Those demands are satisfied by the supply of assets Y, which is some portion of the national stock of assets.

After the reform that demand X continues to exist. However there is also an added demand Z created by the debt repayment mutuals.

An interesting debate. I would like to add a few points:

1. As has already been pointed out, banks lend out a high percentage of deposits anyway. I’m not sure if this change would result in more money being spent, although the *mix* of what it is being spent on may change…

2. However, storage of alternatives would cost money too. Sure, you could buy gold coins instead of a banking fee, but then you would probably want a safe and insurance for peace of mind. As companies such as GoldMoney and BullionVault already have a business model based on providing safe storage of precious metals, people must value security.

3. Just because we are used to “safe” (well, perceived as safe) storage, at no cost, I don’t think people will be aghast if this situation changes. We get very little interest anyway, with every opportunity to charge taken advantage of – one OD charge would wipe out several years of current account interest, I suspect.

4. If people buy ‘stuff’ instead of hoarding fiat, this situation should be enviable. IMO, part of the reason we are in a mess, is because all savings are another’s debt. If fiat was treated as a pure neutral currency, purely to aid in the completion of transactions, but not considered worth holding on to, then the circuit would have fewer blockages. It should be preferable for ‘savings’ to be in assets, not fiat.

5. As assets such as gold/silver etc don’t yield a return (bar speculative gains), I would still expect many people to invest in traditional ways (loans, shares etc).

6. If there was a transitional process, couldn’t people decide whether their money was either ‘timed savings’ (and returning interest) or just stored (with fees as required)?

7. If a limited purpose banking type model was used, it should be relatively easy to sell on shares in mutual funds, if the ‘timed savings’ terms were undesirable.

The problem seems to be over predicting how people will react to the changes. If current accounts start to charge a fee, people may change their habits. People may buy hard assets, people may lend out more money in ‘timed savings’ or the situation may remain unchanged. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to predict how people will react, so IMO, you can only reasonably plan for the medium/long term and try to ease the transitional process.

> 1. As has already been pointed out, banks lend out a high

> percentage of deposits anyway. I’m not sure if this change

> would result in more money being spent, although the *mix*

> of what it is being spent on may change

I’m not sure I understand your point here. I know that banks lend out most of what they get in deposits. That’s one of the points I

was making with the balance sheets I put in the article.

My point here is that demand for bank-account money will fall. That is, people will hold a lower stock of it. Or, equivalently, they will spend down their stock of money more often.

> 2. However, storage of alternatives would cost money too. Sure,

> you could buy gold coins instead of a banking fee, but then you

> would probably want a safe and insurance for peace of mind. As

> companies such as GoldMoney and BullionVault already have a

> business model based on providing safe storage of precious metals,

> people must value security.

Yes, I know. If people switched to holding notes rather than using bank accounts then that would have different costs, such as the costs of security.

> 3. Just because we are used to “safe” (well, perceived as safe)

> storage, at no cost, I don’t think people will be aghast if this

> situation changes.

I’m not saying that they’d be “aghast” and that would be problem. My point here is the macroeconomic effects of the change. That it would cause inflation.

> We get very little interest anyway, with every

> opportunity to charge taken advantage of – one OD charge would

> wipe out several years of current account interest, I suspect.

Banks provide a lot for free. Mostly there is no charge for opening an account and no monthly fee for keeping one open. Normally banks provide the following for free: standing-orders, direct debits, cheque books, statements and paying in.

I’m English, but I live in Ireland, I moved in 2006. At the time I moved the banks were just changing over to the “no fee” policy that has prevailed in Britain for decades. Before that there were charges for cheque books, deposit books, direct debits, standing orders and statements. Even now fee-free banking is often only available to customers who promise to pay their salary into that bank account.

> 4. If people buy ’stuff’ instead of hoarding fiat, this situation

> should be enviable. IMO, part of the reason we are in a mess, is

> because all savings are another’s debt.

I have a small business. Let’s say I want to expand, so I go to my friend Bruce and he agrees to lend me £10K at an agreed rate of interest and repayment schedule. Alternatively, Bruce could give me £10K and buy 20% of my business and therefore become eligible for 20% of the profits.

Why is the latter situation enviable but not the former?

I’ve read loads of stuff that debt-relationships are exploitative and economically unproductive, whereas equity-relationships are noble and economically productive. But, there is no good argument for this. Which is best comes down to the particular situation.

> If fiat was treated as a

> pure neutral currency, purely to aid in the completion of

> transactions, but not considered worth holding on to, then the

> circuit would have fewer blockages. It should be preferable for

> ’savings’ to be in assets, not fiat.

What do you mean by “savings” here? Above I quoted Ludvig Von Mises view on the purpose of money. It says that an individual holds a portion of wealth in money to deal with the uncertainties of the immediate future. I think that’s a very reasonable way of putting the point. So, beyond that immediate future an individual “saves”.

Now, in a pure fiat system that Toby suggests it is certainly beneficial if people do invest their savings. As you say people will have every reason to do that.

But, you’re not comparing the situation clearly with the present day. Under the current system all money balances in on-demand accounts are providing funds for investment through loans. In the modern FRB system only the monetary base is pure fiat money. The rest is matched to assets. This isn’t a problem we need to fix.

> 5. As assets such as gold/silver etc don’t yield a return (bar

> speculative gains), I would still expect many people to invest

> in traditional ways (loans, shares etc).

Yes, so do I.

> 6. If there was a transitional process, couldn’t people decide

> whether their money was either ‘timed savings’ (and returning

> interest) or just stored (with fees as required)?

That would be a modification to the plan, but I think it would be a wise one. Let’s say the plan kicks in on date X. If the government gave them time the banks could declare beforehand what their fee structure would be like after the plan was implemented. They could then give customers the option of timed-savings and storage before the implementation date. That would allow the amount of money-in-the-broader-sense to fall before the plan implmentation date. Then there would be much less of a problem afterwards.

> 7. If a limited purpose banking type model was used, it should be

> relatively easy to sell on shares in mutual funds, if the ‘timed

> savings’ terms were undesirable.

Yep.

> The problem seems to be over predicting how people will react to

> the changes. If current accounts start to charge a fee, people may

> change their habits. People may buy hard assets, people may lend

> out more money in ‘timed savings’ or the situation may remain

> unchanged. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to predict how people

> will react, so IMO, you can only reasonably plan for the

> medium/long term and try to ease the transitional process.

I mostly agree. Though it’s not impossible to predict how people will behave. As I said in the article there have been several historical examples to draw on. Those support what I’ve written in the article.

I’ll respond to the points of contention:

1. My point is that assuming people will volunteer to keep a similar amount of money invested in timed savings, as is lent out from timed savings and FRB combined currently, then I’m not convinced that buying habits will change. Maybe I am missing your point too though?

3. Just to add, business accounts are rarely free of charges, even in the UK. There are usually fees of some sort for most transactions. Clearly, there are costs involved in maintaining the account, but I would imagine that simple accounts could have very low costs; most people are paid their wages electronically and many people do their banking online, so the main costs would surely be ATM usage (and any charges for going OD, bounced cheques etc).

4. The point I was trying to make (badly) is that those currently with savings are the direct result of others going into debt. If we have excessive debt, then we also have excessive savings. While FRB may distribute investment very well in the good times (too well, it seems!), now that banks are hoarding the savings, it has created a blockage in the monetary circuit, making at hard for borrowers to repay loans. As a result, it has become difficult for the banks to meet their liabilities to the savers.

If people had spent more of their money on assets, maybe the banks wouldn’t have invested so much on their behalf (they would have less on deposit). I suppose giving people control over the size of their savings (safe deposits) and investments (timed savings) prevents this being a problem (if we both agree with Ludvig Von Mises here). With that in mind, in a full reserve banking system, it would likely make this a non-issue.

To Paul Green

Post reform, some people may choose to place more cash in timed deposits than keep them in a safe. This will move more money into timed deposits, from bank vaults. This will mean there will be more lending available for business. This is great news. The business that gets lent funds will invest in what they invest into to make more goods and services that can be bought with the money once paid back to the original owner. This will mean that popular assets classes / businesses that are making things people want will go up in value, at the expense of those that do not, and have formally relied on credit money created out of thin air to exist. This will be painful to some and beneficial to others i.e. those that sell things that people really do want and are not bubble based = happy days. Those that have relied on bubble based credit = unhappy days.

To the extent of what this realigning of the economy is, we do not know. I welcome it anyway as it will align savers with investors , consumers with producers much more so that we have today. What we have today is an economy replete with Malinvestment i.e. capital lopsided to support activity for which there is no demand . This is the bust part of the economic cycle. Robert has concerns that it will be too disturbing. I think that is the nub of the matter here.

> 1. My point is that assuming people will volunteer to keep a

> similar amount of money invested in timed savings, as is lent

> out from timed savings and FRB combined currently, then I’m not

> convinced that buying habits will change. Maybe I am missing

> your point too though?

I think this is the crucial point where we disagree. I’d be able to explain it better to you if I know what economic framework you’re most familiar with.

You mention the monetary circuit below, are you a Post Keynesian? If I explained it in a Monetarist way would you understand it better?

In my article I explained the problem in a quite Austrian way, and I expect that’s confused those who aren’t so familiar with the Austrian POV.

I am not sure if the original thread is alive or not, but I will restate my view here but after I comment on this exchange first.

1. Businesses already pay through the nose for banking services. Every cheque, deposit, transfer, statement and even the fact that an account is open with no transactions costs money. This happens because as a ltd co, one MUST have a bank account, so the ability for companies to avoid using banks is not possible. As to the suggestion that companies will try and nett off, well, I can imagine HMRC’s response to that, and the shock from the accountants. I am unclear as to how many companies sell to the same entities they buy from. I do not think it is a significant number.

2. I do think the interest revenue stream aspect of this plan is not a key flaw, it will cause adjustment of what a bank account is and much grumbling and irritation. In Europe, the concept of subsidised current accounts is quite rare, or was about a decade ago.

3. On-lending will still go on and this will increase the broad money supply.

But, on to my main point:

I do believe there is a flaw in this plan. It is an odd one, not immediately seen on the face of it, but very much a problem.

Primarily, you appear to be basing your position on the mistaken premise of “out of thin air” which is patently not true. FRB is an interlinking set of dominoes, a chain of lending obligations, not “out of thin air”. I know it can be used to “explain” FRB to others, but I think it is not explaining, but misleading[1].

You next suggest that current business lending assets held by banks are to be moved to a mutual and all deposits converted to cash. You must move ALL lending out of banks, not just business lending, otherwise what @Tyler May 23rd, 2010 at 23:04 says could occur [2].

If you move those loans out to a Mutual, how can you “immediately” pay off the National Debt? That would presume the Mutuals SOLD those loans on and used the receipts to erase the National Debt[3]. But that is a side issue to the plan and I think we could see the debt being “rapidly” paid off as those loans mature. Again, this is not a deal breaker, but useful to point out.

While the Mutual does not appear to increase the money supply, for it just diverts money that comes from one section of the economy to pay off another, this arrangement does not, in fact, have the same consequences due to what I believe is a fundamental misunderstanding of the Fractional Reserve system as it operates over time.

When loans are paid off currently, the money is either

a) returned to a “depositor” if they decide to, contemporaneously, withdraw cash

OR

b) used to replenish reserves if a) had already happened

OR

c) the bank on-lends the amount again.

In terms of money supply, your proposal is not the same.

When repayments are made in your proposal, the money

a) goes to the mutual

b) Is used by the Mutual to pay off National Debt

c) Those repayments are then BANKED by the erstwhile holder of that debt

Back at the bank with its depositors, the proceeds from the repayment of the Gilts will be banked. In the past, the repayments were to the loans and if a depositor withdrew any money, then on-lending would have to be curtailed by the amount of the depositor withdrawal. But not now.

If a depositor withdraws £100 to buy something eventually from a company that had borrowed money, the £100 leaves the bank, is moved to the company account, used to repay the loan lodged at the Mutual, is on-passed to the Gilt holder and is then re-banked.

Now, this seems to be ok, but what used to happen is that when the depositor withdrew the money to buy from the company and the company paid off its loan? I will tell you – that £100 disappeared. Completely. Gone. Finished. Ended. (Except for a small percentage). THAT is the only “thin air” that exists around here. It was NOT on-lent or available to the economy because the Bank had to replenish its reserves to the point at which it was just before the depositor took out their cash to spend and so enable the repayment of the loan.

I will say that again: because the Bank had to replenish its reserves to the point at which it was just before the depositor took out their cash to spend.

It is thus not available to the economy. It is dead, in a vault.

In your proposal, the depositor spends, the company pays off, the money goes to the mutual to buy back the Gilt and the ex Gilt owner banks the cash and it still exists to be spent at will. All of it.

THAT is how your proposal inflates the money supply.

I claim my £1000.

[1] I do wonder if much of the energy towards 100% reserve is based upon just the mistaken premise of “out of thin air” and the outrage it would generate, and in fact generated in me until I worked out how FRB operates.

[2] If all loan assets are converted to cash, I want to set up a bank just before you switch over, please. I will open a string of accounts, lend myself money, deposit it back, lend it out, deposit it back until I can do so no more, then you convert all the deposits to cash and then I use that to pay the (i.e. my) bank back, shut up shop and retire.

[3] Fact is, who is going to buy all those loans, or are you planning to create an SIV to sell them or the mutual that contains them? Do you think a ratings agency would be needed and some insurance in case of default? In a way I am joking, but I am also serious. One could say that the interest payments should balance out the loans that are defaulted on, also.

Interesting post, but isn’t that the point of printing the money? That is, to sustain current level of broad money supply, rather than allowing it to contract through credit repayment. In other words, rather than inflating the broad money supply, it would just be maintaining the current levels.

I’m not convinced the paying off the national debt part of the proposal is a good idea or workable. I could imagine it going rather pear shaped if something wasn’t considered (perhaps the above point, perhaps another). It just seems too close to a free lunch, which usually suggests consequences.

I would be more inclined to take a gradual approach to reform, by letting some existing obligations run their terms (such as bonds), while drawing a line between instant access and timed savings. People would also get to define their contractual terms of either safe keeping or investment (which could gain or lose), along with the advantages/drawbacks of each. This would clear up the legal contentions and remove the instability and moral hazard which FRB can result in. If more people wanted instant access (rather than timed savings) than reserves could cover, the difference could then be ‘printed up’. This amount may be a relatively small, limiting any unpredictability of hitting the presses.

BTW, at the risk of straying off topic, I would suggest that as part of the process of moving to having more timed saving accounts, the market was opened up. The limited purpose banking idea of them being shares in mutual funds, which could be traded is compelling. Making timed savings less restrictive would surely go a long way to easing the transition.

Actually, I am going to suspend my “flaw”, as I think it may well be in error, so right now I hold with my other views that the bank charges are not a fatal flaw.

What I am concerned about, though, which was dropped from a longer version, is that banks will seek to create again de facto on-demand arrangements to leverage the money supply up again.

Tim, you say “is that banks will seek to create again de facto on-demand arrangements to leverage the money supply up again” That may well be the case. As you know, if there is a tax change say like we have just seen here from capital gains tax of 18% to 28% and top income tax a 50%, there will still be “income shifting” as people have an incentive to make income look as much as possible like a capital gain. Cat and mouse is played between the revenue and the private accountants employed by people. So this reform must nerve be done unless there is a constitutional amendment enacted that stops the government from abusing the system and stops banks from doing the same. Sir Isaac Newton when Master of the mint hanged people. I would not suggest this but just keeping on top of the law and enforcing it.

> 1. Businesses already pay through the nose for banking services.

> Every cheque, deposit, transfer, statement and even the fact that an

> account is open with no transactions costs money. This happens

> because as a ltd co, one MUST have a bank account, so the ability

> for companies to avoid using banks is not possible.

Yes, and I think the situation would be pretty much the same for customers. They would have to use banks and pay the associated fees. But, both can take steps to reduce their exposure to fees.

> As to the suggestion that companies will try and nett off, well,

> I can imagine HMRC’s response to that, and the shock from the

> accountants.

AFAIK netting off is entirely legal in the UK. I’d appreciate clarification from anyone who know more though.

> I am unclear as to how many companies sell to the same entities

> they buy from. I do not think it is a significant number.

Think about how many could if there were banking fees to avoid.

An example…. I was talking to a barman a few weeks ago, he worked in pub X, I met him taking beer out of pub Y. I asked him what he was doing. It turns out the pubs have a kind of exchange deal. If pub X runs out of some type of beer then it has the option to draw on the stock of pub Y. This agreement is reciprocated by pub Y. I found that one pub that serves Heineken has no contract with the brewery for that beer. It buys Heineken from the other pubs using both cash and other beer.

Now, imagine how pubs would behave if the charges for bank transfers were raised. Rather than pay the extra charges they would instead collaborate in this way more often. They could do what was done in the 19th century and allow bills to be passed around.

> I do think the interest revenue stream aspect of this plan is not

> a key flaw, it will cause adjustment of what a bank account is and

> much grumbling and irritation. In Europe, the concept of subsidised

> current accounts is quite rare, or was about a decade ago.

When the changes in bank charges occurred in Europe they happened during a period of central banking. So, the central bank could compensate for the change. This is one of the things that central banks do, it’s implicit in the currently-fashionable idea of interest rate targeting. The amount of monetary injection that’s needed to hit a particular rate target varies from time to time because of changes like this. The central bank compensates by adjusting it’s levers. Though it isn’t often talked about this is being done all the time.

Under Toby’s system though there is no central bank to do this after the plan is implemented. Now, I certainly believe that “no central bank” is a good thing long term. But, the short term is different in this case.

> 3. On-lending will still go on and this will increase the broad

> money supply.

If the government ban creating money-substitutes then I think that ban would be effective. A money-substitutes is something that must be widely accepted. In most cases that means that it cannot be underground, it must be done openly. That can’t occur without the state’s consent.

However, debt contracts are a completely different matter. States have periodically tried to legislate against debt contracts for centuries and it often hasn’t worked. And, as I explained earlier debt contracts can be used to reduce the need to hold money.

> Primarily, you appear to be basing your position on the mistaken

> premise of “out of thin air” which is patently not true. FRB is

> an interlinking set of dominoes, a chain of lending obligations,

> not “out of thin air”. I know it can be used to “explain” FRB to

> others, but I think it is not explaining, but misleading[1].

Yes, you’re right about that. And I agree that the 100% reservists have used to accusation to fan the flames of discontent.

Rothbard sometimes infers that not holding 100% reserves is equivalent to insolvency, which it isn’t.

> You next suggest that current business lending assets held by

> banks are to be moved to a mutual and all deposits converted to

> cash. You must move ALL lending out of banks, not just business

> lending, otherwise what @Tyler May 23rd, 2010 at 23:04 says could

> occur [2].

That’s true temporarily. Just before the reform – specifically in the period between when it is certain to occurs and when it occurs – many perverse incentives occur. People have a great incentive to set up dodgy banks so they can acquire the 100% reserve later. So, the government would have to do something about that. Such as banning the formation of new banks. The more difficult problem would dealing with how the existing banks would behave. However, afterwards once 100% reserves are established that period ends.

What you go on to describe sounds like a theory that in the 19th and 18th century was called the “Real Bills Doctrine”. It’s the idea that debt and money have an organic relationship. Adam Smith and the “British Banking School” pioneered this view.

The problem with this view is that it doesn’t really describe how banking systems with central banking and fractional reserves work.

In a modern central banking system the central bank authors *both* sides of it’s balance sheet. That is, the state says what reserves are and it says what assets are. It does this by fiat using its forces of coercion and (as Post-Keynesians point out) the enforcers are taxmen.

Now, in normal circumstances it works like this. There are £X billion of good loans, this amount it endogenous, the state do not push in one way or another. (Except through ABCT, but that’s another story). The state require that the banks keep a particular level of reserves against on-demand accounts (a required reserve ratio). The state don’t normally require this for other sorts of liability like bonds. So, there is £Y billion of balances in on-demand accounts, which is quite a bit lower than £X billion. The difference between the two of them is made up using timed-savings such as bonds, which don’t require reserves.

Lets say some proportion of loans to a bank are paid back using notes. Now, since these are reserves the bank can expand it’s liabilities in on-demand accounts. However, this can’t happen systematically, since the amount of circulating reserves is limited by central bank. Unless someone finds a dusty pile of notes in their attic the reserves that one bank gains are always being removed from a different bank. Second, lets say some proportion of loans to the bank are paid back using inter-bank transfer. This means that normally reserves and the required-reserve ratio determines the total amount of on-demand liabilities.

As I mentioned earlier this situation is breaking down currently due to the strange decision of the Fed to pay interest on excess reserves. But, that’s a separate issue.

Tim, all of this has been answered in your original post. I do not intend to do it all over again. If there are not sufficient answers, please get back to me.

Toby.

This reply is in two halves. The latter refers to your response at the old post. The first talks about the idea in other terms.

In your plan you say there is no Central Bank and that banks hold the cash on deposit in their vaults, matching deposits at the branch level?

If so:

a) Interbank settlements will still require central clearing accounts to enable painless netting off between banks or we could see a huge rise in Armoured Car heists. A central clearing vault bank or banks will be sensible, but where would the capital come from? Banks are not free to take deposit cash away from the home branch, surely, for then those accounts are not on demand.

b) Even if cash is held for interbank settlements from the bank profits, a form of interbank lending will still need to occur to cater for extraordinary interbank transfers or expected events known to those who understand chaos theory. But banks cannot lend that easily, can they? To me any currency needs a lender of last resort, that being the issuer of that currency, even in the world of Free Banking, which would see multiple LoLR, one per currency.

c) Bank branches themselves would nett off against each other, but at some stage large amounts will need to be moved each day if you truly say that the bank holds your money in cash on demand.

c) I can envisage limitations on cash balance withdrawals, which I suspect will be little different from those that apply now (one needs to call if one is withdrawing over £5k or so in cash). This will push people towards new accounts and instruments such as forms of overnight settlement. Leave to bake and you will increase the defacto money supply massively.

d) I think your move will push banks to move away from, or, penalising the use of, cash, for it will be difficult for them to manage. They could ask for people to have “cashless” accounts and so not need to keep any cash in the branch for their accounts, and keep it all safely at the central clearing vault.

e) End the use of cash and we are, frankly, dead meat in a number of ways.

Now to the previous reply…

Well, you may have missed that I had suspended part of my objection and that was to do with a slip-up I made in the reckoning of reserves as the money flowed, that is all. No excuses from me, I raised my hand to that error right here.

Still, in your reply at the original post you do yourself present errors*.

TimC said: ““When loans are paid off currently, the money is either

a) returned to a “depositor” if they decide to, contemporaneously, withdraw cash

OR

b) used to replenish reserves if a) had already happened

OR

c) the bank on-lends the amount again.”

TobyB said: “If a) happens, it does not go back to the depositor as the loan originated from the bank itself and was created ex novo or ex nihilo , out of thin air. So when repaid back it goes back from whence it came, to thin air, unless c) happens.”

Wrong. There is no thin air. Things being equal, if a depositor withdraws £100, the bank would use the next £100 of nett cash deposits to rebalance reserves and would not on-lend. Had the depositor NOT withdrawn, then the next £100 of nett cash deposits would result in £90 of lending (given a 10% reserve ratio). No money was “created”. If it were, show me when it appears together in the same place. Note: a statement is not sufficient!

You then go on to say:

TobyB said “Consider A deposits at the bank B £100, B lends Entrepreneur C £100 who deposits at bank B. There are now £200 units of money when there was only £100 to start off with. When Entrepreneur pays back his loan i.e. the £100 to Bank B, then money supply is then £100 again, unless the bank creates it out of nothing again and re lends.

The problem today is there is more paying back and less lending i.e. a “credit crunch.””

There is NOT “£200 units of money”. Show me where they are. Lets try and find them…

If the borrower took the £100 out in cash before it deposited in BankC, BankA would have to not on-lend the next £100 in deposits it receives to rebalance their reserves (as above). If the borrower used a cheque or electronic means, still, £100 would have to be transferred from BankB’s account at the BoE and sent to BankC’s account at the same place. As you should know, these accounts are hard money, not your “IOUs”.

If everything occurred in the same bank, the depositors money was lent to the Entrepreneur who borrowed then deposited it in that same bank, there is still only £100 of money, as in £100 of reserves, that the bank can on lend again, for the Entrepreneur has, de facto, lent their borrowings back to the bank. If demands on either of those accounts occured, if both tried to withdraw, for example, then you will see that there is only £100 units of money and not £200.

BTW, the Bank does not issue IOUs at all. I don;t have one from my bank. All I have is a statement. If I had an IOU, I could sell it on, but I cannot for they do not exist. If I transfer money from one bank to another,IOUs are not passed around, but cold hard cash.

This “IOU” meme is another reason why people get hot under the collar about FRB, for it is often used to segue from the “goldsmiths” story into modern banking. Remove the conceit of the IOU and then people are not so easily tricked into thinking that there is more money about.

What FRB does is turn stills into movies. The money flickers by so fast it appears to be motion, but is always, in truth, still pictures.

And the final point you made

TobyB: “If £100 is owed to gilt holders ”

At no stage did I say this flow was inflating the money supply, for it is just a flow from debtor to creditor. Your complication misses my point and serves no purpose.

* it is not helpful to assert that people do not understand FRB “at all”. Absolutes are rather dangerous things.

To Tim Carpenter

Your point a) as discussed on these comments section, the govt could undertake to print cash and not actually print it unless it is demanded. If it did, I would think clearing house services were the net movement of interbank money is physically moved at the end of the day could take place as existed for many centuries when gold was money.

Your point b) I do not understand what you are suggesting here.

No lender of last resort is needed in a full reserve environment. Just like with all companies that are full reserve , except banks which have legal and accounting privilege to operate on a fractional reserve , a full reserve bank would go bust and have no LoLR bailing them out. As a liberal free marketer, I can’t tolerate grants of legal privilege or state involvement in something so serious as money especially when the State has failed so badly.

Your point c) If all cash is printed which is what I suggest; I would hope that it would be in my vault so no “calling” necessary.

Your point d) yes they could, it would be interesting to see what solutions in a free market people come up with.

You say this “TobyB said: “If a) happens, it does not go back to the depositor as the loan originated from the bank itself and was created ex novo or ex nihilo , out of thin air. So when repaid back it goes back from whence it came, to thin air, unless c) happens.”

Wrong. There is no thin air. Things being equal, if a depositor withdraws £100, the bank would use the next £100 of nett cash deposits to rebalance reserves and would not on-lend. Had the depositor NOT withdrawn, then the next £100 of nett cash deposits would result in £90 of lending (given a 10% reserve ratio). No money was “created”. If it were, show me when it appears together in the same place. Note: a statement is not sufficient!”

There is now £100 of original money in the system which sits as a bank IOU and £90 of lending and £10 in reserve which does sit in cash in the above e.g. right or wrong? So the £100 of bank IOU is made up of £10 reserve cash and £90 of bank journal entry or bank IOU. So £100 has become £200. You do not like calling this “out of thin air,” I do not know why, it sure as hell looks like it. Also, form my old “A” Level text book to my undergraduate text books to all things that I read and observe in the world, I believe this is not a contentious point at all. When the £90 loan is paid back, we then have the £90 money taking the place of the bank IOU of £90 and £10 of reserve. So we are back to £100. This is the worst case scenario for the banks, so most of the time they make sure they lend it out again.

The situation we have today is more is being paid back and less being lent out than is being paid back. This is a money deflation.

With respect, I do believe you need to go back and re read some basic text books on the bank credit creation multiplier, I am saying nothing controversial here at all. Your misunderstanding clouds all what you say.

I am sorry I can’t be more polite in the matter.

Toby,

If, as you say, all your cash is in the vault and so no need to have a call, what if you pay a company that has a bank account in another branch elsewhere in the country?

Even with netting off, each day one may have to move sums, potentially, from each bank branch to each branch of all the other banks in the country or at least to their regional distribution centres one for each bank from which it would need to be distributed. One would have to work out the ideal cash transfer arrangements between each counterparty to branch level or some other arrangement. Any attempt to make efficiencies via clearing and settlement intermediaries would, I suspect, still require significant sums of dead money from bank profits sitting about in vaults to reduce the need for physical movements of cash intra bank. This would not solve the inter-bank transfers.

In the past we could operate with hefty reserves parked at the Bank of England, but we cannot do that now because we need to keep EVERY branch fully stocked with hard cash. Any “reserves” at a central clearing location would have to be from bank collateral and profits and even so, they cannot solve everything and probably solves far less than we expect. You might find that a bank is unable to actually distribute vast amounts of its profits.

This is a major hurdle. I would suspect that in solving this problem, banks would devise mechanisms that might undo your scheme in terms of money supply.

On to the next issue.

TB “There is now £100 of original money in the system which sits as a bank IOU and £90 of lending and £10 in reserve which does sit in cash in the above e.g. right or wrong?”

I disagree mainly because you think this “Bank IOU” exists. Where is it? If it is mine, I should hold it or be able to sell it on. I cannot. Banks do not sell on these IOUs you speak of to other banks, the transfer (but mainly nett off) cash between their accounts at the BoE.

If £100 is paid in, the bank can lend £90 of it, keeping £10 in reserve. Certainly.

If the borrower or the person they spend the money on deposits it in the same bank, the bank can on-lend £81 of that £90 and so on. All the time we have £100 of original real money in the vault until almost£900 is lent out. If at any stage money lent is transferred out of the bank or withdrawn, the lending mutliplier has to stop until fresh cash is deposited. The “IOUs” you invent are not money. Nobody wants them. I cannot use them. I cannot see them. Other banks will not take them.

They, the IOUs you speak of, in terms of “money”, do not exist in any practical or meaningful way. Ergo they are not “money”.

Of course there is a journal entry under my account saying they owe me £100, but that is all. Hardly an IOU. This “IOU” meme comes from the story about goldsmiths, when they issued their bearer scrip. Banks running FRB in modern Britain do NOT issue bearer scrip when you deposit. They just say thanks and send you on your way empty handed.

So today if the bank took my deposit, lent it, the borrower foolishly kept it in the same bank and then the bank lent it out again to someone who withdrew it, we have:

£19 in the vault (10% reserve on my £100 and the re-deposited £90) (asset)

£90+£81 in loan agreements (assets)

£190 in liabilities (what they owe me and the depositing borrower)

19+90+81 = 190.

These liabilities are not IOUs, not money. They cannot be used by the bank or by me to exchange it for money, goods or services. they are on the other side of the equation – they are DEBTS.

Just because this “IOU” explanation is all over the internet and even in A-level schoolbooks does not make it correct and does not give you the justification to accuse people of not knowing what they are talking about.

So, again – please show me where your IOU is that can be treated as money. Do not say “your deposit account”, for that is not true. Any transfers are funded from reserves until fresh deposits or netting off restores it as I have outlined. The reserves are a buffer to smooth out transactional flow over time.

I know you cannot show me these IOUs, for I know they do not exist in terms of “money”.

Your plan exchanges your misunderstanding for hard cash.

No deal.

Morning Tim,

Your first point which I will summarise as “is it practical to have each bank full of physical cash so that each day interbank settlements will need to take place physically?”

As said in many of the Emperor comments, a clearing house system may emerge and/or you do not even have to use physical cash if the government has just pledged to produce the cash i.e. have it all done electronically as most of it is today.

As said at the start of the Emperor article, it seeks to establish theoretical possibility not practical possibility first. No point in even moving to the practicality of the whole scheme if in theory it falls at the first hurdle.

I believe it passes the theory test. I thank you for your contributions to that debate. The practicality test is another matter (thank you for your contributions here if premature!), then post that test is the political will test and that is another matter in itself.

Your next contention is simply wrong. A demand deposit is money. I can write a cheque to pay for my newspaper; the newsagent takes it and banks it, a journal entry from my bank to the favour of his bank happens. Thus it is money!

Enshrined in banking law , I reach for my 1991 edition of “The Law and Practice of Banking, Vol 1, Banker and Customer, J Milnes Holden, ” Pitman Publishing. Granted, this may be out of date.

Page 55 discussing Foley V Hill “In the result, the implied terms of the contract between banker and customer in the ordinary course of business when a current account is opened, may be stated as follows.

2.10 The banker must receive cash and collect the proceeds of such items as cheques, postal orders, money orders and bills of exchange for his customer’s account.

2.11 the money so received becomes at once the property of the banker, and he is thereupon indebted to his customer for an equivalent sum; hence the banker does not hold the money as his customer’s agent or trustee.”

This is an agreement of debt from the bank to the depositor. In plain layman English, this is an IOU.

A journal entry is passed from bank to bank as you the depositor exchanges goods and services and do not seek to redeem your debt in cash. The bank has no obligation to redeem its debt in cash until you demand it (this is why banks are exempt from the Statue of Limitations Act). If you do not demand it in cash, it has no choice but to swap a journal entry in its bank for that in another. This is money; it is a very important component of the money supply. Economics, banking and accountancy law are happily unanimous on this matter.

There is a certain amount of wheel-reinventing going on above. Karl Marx, Abba Lerner (born: 1903, died: 1982), and Milton Friedman all advocated at some time or other monetary systems which involved no national debt. For Friedman’s contribution, see http://www.jstor.org/pss/1810624

Such a system is perfectly workable, in my view, thus a move from our present system to a zero (or much reduced) national debt should be easy enough, and indeed it is. Governments wanting to do this should proceed thus.

1. Print money and buy back the debt. 2. That would be too inflationary, so mix “1” with a deflationary method of buying back the debt, i.e. get some of the money for the buy back from raised taxes and/or reduced government spending. Q.E.D.

Incidentally that has nothing to do with whether the commercial banking system should be fractional or full reserve. The above national debt reduction system would work if there were no commercial banks at all and people held the bulk of their cash and gilts under their mattresses (with the rest being held in accounts at the central bank).

> 1. Print money and buy back the debt. 2. That would be too

> inflationary, so mix “1” with a deflationary method of buying back

> the debt, i.e. get some of the money for the buy back from raised

> taxes and/or reduced government spending. Q.E.D.

Ralph, using that Post Keynesian logic there is no reason to worry about the national debt at all. The national debt doesn’t have any real economic significance, it’s level is a tool of policy.

Current: I think there IS something to worry about if the debt just goes on expanding ad infinitum.

Re your phrase “the national debt doesn’t have any real economic significance”, I rather agree. Taking the simple case of a closed economy, national debt arises where a government chooses to borrow from its citizens in place of taxing them. There is not a HUGE difference between the two: that is, the national debt is not of huge economic significance. In fact I’d describe it as one big nonsense.

I put a paper on the net in January which attacks the whole idea of government borrowing:

http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/20057/

Also I’ve just done an updated version of the latter which I’m submitting to an economics gathering in Greece in a month’s time. This updated version should be on the latter “uni-muenchen” site in a week or two.

Have you read about Austrian Capital theory?

I’ve never read anything about the Austrain Capital Theory. So I Googled it and read a couple of papers, and wasn’t impressed. I then came across a third paper which concludes with a similarly jaundiced view of this theory.

http://www.utas.edu.au/ecofin/hetsa/HETSA%20ABSTRACTS%202003_files/pdf_papers/Lynch.pdf

Don’t think I’ll take my studies much further!

Well, I would argue that the author of that paper hasn’t taken the time to study Austrian Capital Theory properly. His critiques are really quite ranty. I can’t comment on the other articles you’ve read since you haven’t actually mentioned what they were.

The issue here is that many economists accept the “homogeneous” theory of capital which considers all capital goods to be the same. If you accept that theory then what you say above is quite right, debt and taxation become closely related. However, this doesn’t make any sense if you have an inhomogeneous theory of capital.

If I interpret your views about correctly you are a type of Post Keynesian. Have you read about the Cambridge Capital controversies? Do you know the difference between Post Keynesian and Post-Keynesian?

In his criticisms Lynch says that Bohm-Bawerk lost his argument against Clark and Hayek lost his against Knight. That isn’t really correct, there was no general agreement at either time. The same is true of the later Cambridge capital controversy.

How do you look at it? Do you agree with the homogeneous theory of capital?

Quite – you are both right.

Though it is well worth remembering that QE is really forward starting debt, as when the debt you buy with the newly printed money matures, you either have to issue more debt to cover the repayment (hence forward starting debt) or you have to withdraw the QE.

QE can go on forever in thoery, but at the cost of ever increasing moeny supply.

I’ll come to my constructive criticism in a second, but first let me just state that Toby will never pay out the 1000 GBP, despite the obvious and quite massive flaws in his argument.

His plan is nothing more than money printing on a massive scale.

The banks are effectively gifted money, which is then used to pay off the national debt, and reduce taxes. If only it were that easy, surely?

Toby states that this injection of money into the banks actually increases their net value, yet does not increase money supply.

Apart from the laughable idea that you can actually fix the money supply (apart from in a closed system, which our economy is not), he ignores basic principles of accountancy and economics.

In simple terms, you can either print the money, back up all customer deposits and pay off all national debt etc, but by doing this you are giving banks a license to print unlimited amounts of sterling. Your money supply in this case will not so much increase as go atmospheric.

Your other case is to inject moeny into banks, but that money must be repaid. That can be a temporary increase to the money supply, but thanks to a bit of basic accountancy, the bank would not be worth any more, thus you couldn’t use that money to pay off national debt etc.

let me demonstrate. I run bank A, which has X in capital, all from demand deposits. I then set up a property company B, and lend capital X from A to B. The government then comes and gives me X to make my demand depositors whole. I repay all of them from bank A. I then have company B repay bank A, so now we have a situation where I have legally tapped the government for X, in the process “doubling” the money supply.

What Toby misses is that I can do this trick legally ad infinitum, tapping the government for as much money as I want. In the process inflation would go through the roof.

Yes, it would pay the national debt off – by inflating it away. Toby seems to be confusing Keynesiansim (via this cash injection, which is nothing more than QE) and the Austrian school by draping an overlay of bank credibility over it…..so lets now deal with his other main point – 100% demand capital to cover demand deposits.

100% demand deposits simply turn a bank, whose job is to group credit and lending facilities and alter their effective maturities to match borrowers and lenders, using the wirder credit market to meet the difference in cash flows. In Toby’s world, the bank becomes nothing more than a safety deposit box, given they are no longer allowed to lend out their demand deposits.

This would have a massive effect on all lending and investment. It would kill the mortgage market at a stroke, as those demand deposits would not be able to back mortgage lending. He argues that this function would be provided by timed deposits, but in reality, this would not happen to any great extent.

Mortgages are too illiquid. Why would I allow a bank to convert my demand deposit into a timed deposit which they would invest in a very long dated, credit risky and totally illiquid product – someone else’s house. I wouldn’t be able to unwind the investment if needed the money, without the bank finding someone able to step into my position. Instead, I’d go and invest in liquid assets such as equities or bonds. Mortgage markets would be killed.

Current makes many good points in his piece above, which I see no need to reiterate, but let me finish with this;

Toby – you are trying to attempt two different things. Firstly, making a fiat currency “good” by trying to limit credit exposure and the money supply. Straight from the Austrian school. You try and pay for it by printing money – undoubtably Keynesian, with the effect on the money supply and inflation that would entail.

To Tyler

Error 1.

“The banks are effectively gifted money, which is then used to pay off the national debt, and reduce taxes. If only it were that easy, surely?”

Wrong, the Plan says that the people who are current bank demand deposit holders are given the money. This means that the banking system has no demand deposit current liability. This means their net worth has gone up by the exact same amount that their current liabilities have gone down by. The surplus assets thus created can then be packaged up into Mutual’s or a special purpose vehicle whose only purpose is to pay off the debt.

Error 2.

You say “this injection of money into the banks actually increases their net value, yet does not increase money supply.

A swap of one type of money a demand deposit for the same cash value can’t increase the money supply. You swap one demand deposit money unit worth 1 money unit (with is in fact a bank IOU to the depositor) for a cash money unit also worth one money unit. To put it in even simpler language 1 is swapped for 1.

Mistake / Misunderstanding 1.

Your say “Apart from the laughable idea that you can actually fix the money supply (apart from in a closed system, which our economy is not), he ignores basic principles of accountancy and economics.”