Sean Corrigan has been interviewed by the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. German readers can view the original article.

For the sake of the rest of you, here’s a translation:

Germany is the scapegoat of the world for its austerity measures (there is no real austerity because debts are high and rising dramatically). Even Soros and Krugman are lamenting about the “hair-shirt politics”. Your take?

This all presupposes that if the government does not prop up activities which by virtue of that very government support are not viable, all the consequences are bad. It forgets that if the service provided is really valued by its consumers, someone, somewhere will step in to offer it privately – probably more reliably and at a better price, too! It also neglects the fact that if the government borrows less, there is more room for capital formation in the wealth-creating sectors; that less government demand means lower costs for entrepreneurs and end consumers; that greater budgetary discipline means more money left in individuals’ pockets to use as they see fit – not as some distant bureaucrat decides.

If ever more government was the answer to the problem of prosperity, why were the guards and machine guns not on the Western side of the Berlin Wall for all those years?

How is it possible that the debtors are the good guys and the savers the bad guys?

Because the mainstream is still far too heavily influenced by Keynes’ theories of under-consumption and perpetual slump. After all, these are the same people who argue that World War II had its plus-side in that it finally ‘ended’ the Great Depression, by carting the nation’s youth away from the jobless lists and off to the front and by destroying untold capital so as to remove an imagined ‘surplus’!

The only ‘fault’ of the savers is that they had – perforce – to lend more and more money to their worst customers – but we can blame not only too low interest rates (i.e. the Fed and its friends) for that, but also the fact that once the single currency removed FX risk from a periphery all too used to borrowing at double-digit rates, nobody bothered with the remaining credit risk when they gave out their loans at what must have seemed give-away levels to their unbelieving recipients.

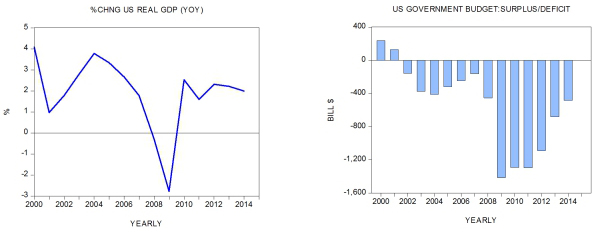

Where will the American debt spiral lead us to?

Well, this is part of the irony of the present assault on Europe – that the US arithmetic is hardly less scary than anything the PIGS may have to offer. In the end – and who knows how long this will take to come to its bitter fruition – the US will have to renege on the promises its politicians have offered all too freely to its people – either by a drastic reform of the tax and welfare system (and here the scale of the adjustment is so frightening as almost to rule it out), by repudiation of its debts, or by naked inflation.

How long will the markets tolerate the American strategy of big government spending and what will happen if a critical tipping point is reached?

This is hard to say. After all, we have the present paradox of seeing people buying US government debt at, in some cases, negative real yields at the same time that they are buying gold – simply as a safe haven trade. But, as long as central banks – both at home and abroad – either buy this debt directly or offer nearly free money to the commercial banks who buy it for them, these ludicrously low yields can persist. But, once again, it is a sign of the dysfunction of our system of finance, not something of which to be proud. We are again misallocating capital and distorting the key price signals in the economy and this can only destroy more wealth.

What has to be done to return to a sound economic system (in the States and elsewhere)?

All the things no-one wants to do. Balance budgets, shrink the state, promote enterprise by leaving it in peace and making sure that the tax code fosters capital formation, make money as hard as possible, apply accounting rules properly, and outlaw fractional reserve banking. The adjustment would no doubt be very painful for a generation which has spent its whole lives being forced to act as over-borrowed speculators when its members buy their houses or save for their retirement, but it could also lead to a new Wirtschaftswunder.

Your take on bail-outs and regulation – (what will happen if the Volcker-rule will be watered down)?

I am sure that whatever final form the legislation takes, it is not going to be more than an inconvenience for the financial oligarchy whose members presently enjoy so much influence. Even if we do a Standard Oil or a Ma Bell and split the banks into some ‘non-universal’ units, I am sure that they will grow just as monstrous over the course of the next cycle – and will prove just as adept at gaming the regulations. No one will repeal deposit insurance, back money with a hard, scarce asset, and insist that banks hold 100% reserves – and, maybe even ban them from holding government debt! – until we do, we are not addressing the root of the problem

What do you expect from the G20-meeting? Will Tim Geithner and Larry Summers succeed with their obtrusive “spend now, consolidate later” message?

I am sure Chancellor Merkel’s team will be every bit as strong willed as their American counterparts!

What should G20-leaders do?

Insist on proper accounting, stop intervening, get their own finances in order, and stick rigorously to the rule of law. A very slim hope!

How to behave as investor?

Cautiously. I think the economy is on the verge of losing a good deal of its recent upward momentum. Whether that means an outright decline is too early to say, but it does look like the ‘stimulus’ is beginning to wear off with many problems left unresolved – and even, in some cases, made worse. Hence, things are very fragile. If markets take fright once more and trade and production begins to suffer, I would anticipate another wave of central bank money printing. We may not light the inflationary flames just yet, but we will certainly put a lot more wood on the bonfire if the recovery falters.