In September of last year, I placed this article up on our web site detailing the theoretical errors behind the policy of quantitative easing. Clearly, as the MPC has now been given the green light by our chancellor, we expect this currency debasement to be starting soon. All it will “achieve” is a wealth transfer from those lucky enough to get the newly minted money, from those not luckily enough. I aimed to expose the faulty crank-economics that lies behind such thought processes last year and did not think a Tory government would be so foolish to let this happen under their watch, especially as they condemned it under a Labour government. Sadly, articles like this one need to be reproduced so that a new set of readers can hopefully have influence on the present administration.

The mainstream economists hold that the volume of money in circulation, times its velocity is equal to the prices of all goods and services added up. This is the famous Theory of Exchange, MV=PT, or the mechanistic Quantity Theory of Money, where:

- M is the stock of money,

- V is the velocity of circulation: the number of times the monetary unit changes hands in a certain time period,

- P is the general price level,

- and T is the “aggregate” of all quantities of goods and services exchanged in the period.

It is held by the overwhelming majority of all economists, that if the velocity of money falls, the price level will fall and thus it is the duty of government, the monopoly issuer of money, the chief Central Planner of the Money Supply, to create more money to keep the price level where it is and thus preserve the existing spending habits of the nation.

Error One — the stock of money

It is held that if you can count the monetary units in the economy and their velocity, you can say what the price level is. As people find it very difficult to count the money in an economy, they cannot see the statistical relationship showing up mechanistically in the price level as expected: the authorities do not have a measure of the money supply which correlates to economic activity.

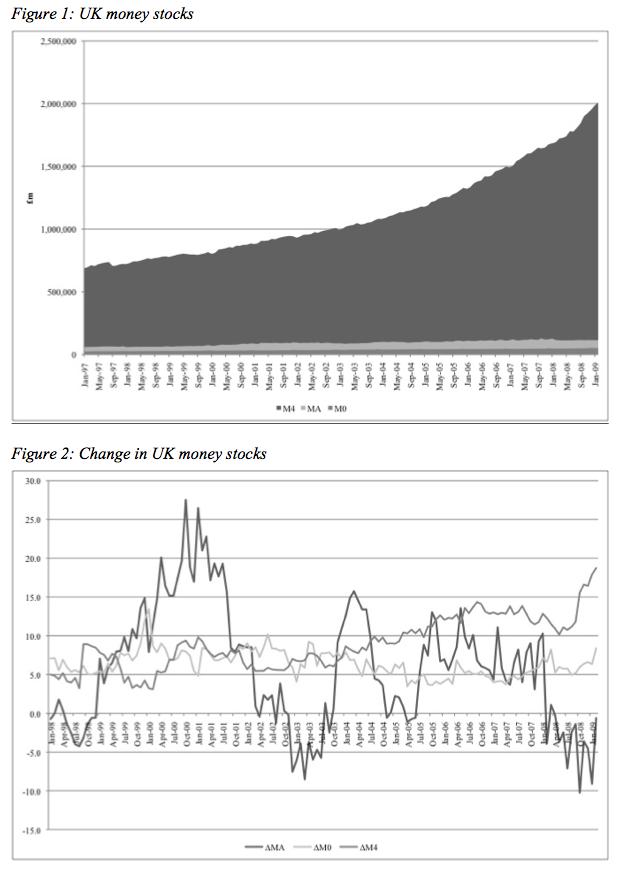

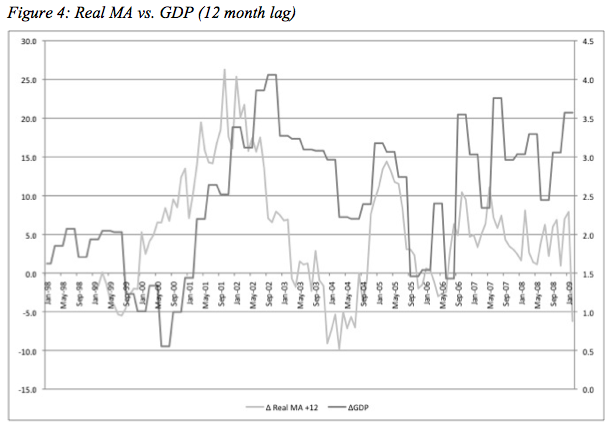

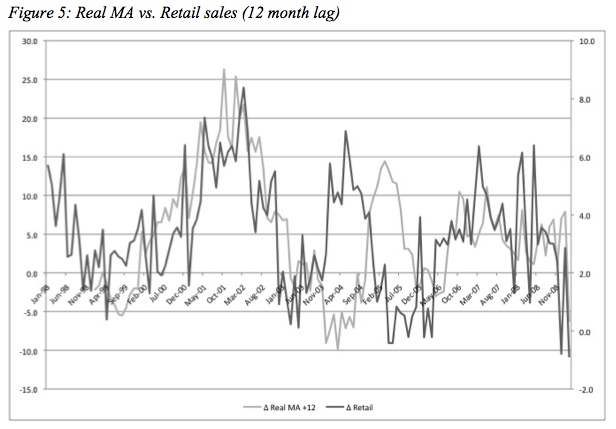

Working from a sound theoretical basis, I and my colleague Anthony Evans can show you how to count money exactly and how that measure of the money stock correlates to economic activity:

Note that changes in the mainstream measures — M0 and M4 — are quite different to changes in our measure — MA. However, it is MA which shows the best correlation to economic activity and not the measures used by the Bank of England and HM Treasury:

The monetary authorities do not have an adequate measure of the money supply.

Error Two — the velocity of circulation

Velocity is defined as the average number of times during a period that a monetary unit (I will call this MU) is exchanged for a good or service. It is said that a 5% increase in money does not necessarily show itself up with a 5% increase in the price level. It is argued that this is because the velocity of money changes. The trick is to measure by how much the velocity has declined and then create new money — cross your fingers, pray to the Good Lord, do a rain dance around a fire, and hope that the new money will be spent — to fill in this gap left by the fall in velocity.

When you buy a house, we do not say it “circulates”: money is exchanged against real bricks and mortar. The printer who sold me books would have had to sell printed things (i.e. real goods) and saved (forgone consumption) for the future purchase (act of consumption) of the house. Imagine selling your house backwards and forwards between say you and your wife 10 times: the mainstream would argue that the velocity of circulation had risen!

Yes as daft as it sounds, this is the present state of economics.

Thus, if the velocity has gone up by a factor of 10, the price level has increased by the same factor. Here is the suggested rub: therefore, when the velocity of circulation falls, if you increase the money supply by the same factor that the velocity of circulation has fallen by, the price level will stay the same.

Note, as explained above and in detail here, the mainstream do not actually know what money is. Well, let us be clear: it is the final good for which (all) other goods exchange. All of us who are productive make things for sale or sell services, even if it is only our own labour. We sell goods and services which we produce or offer for other goods and services we need. The most marketable of all commodities, money, is accepted by you and other citizens and facilitates exchange of your goods and services for other goods and services. Note that, at all times, money facilitates the exchange of real goods for other real goods.

Party one and a counterparty exchanging or “selling” the house between one another 10 times causing an “increase in velocity” and thus an increase in the price level as an idea is utter garbage. If one party had sold real goods and saved in anticipation of buying the house — real bricks and mortar via the medium of money — this would facilitate a transaction of something (the party’s saved real goods) for something (the counterparty’s real house). Printing money to make sure the price level stays stable to facilitate the “circulating” house in the first example will facilitate a transfer of nothing (the paper) for something (the house). This is commonly called counterfeiting.

This may be another helpful example of why velocity is utterly meaningless. Consider a dinner party: Guest A has a £1. He lends it to Guest B at dinner, who lends it to Guest C who lends it to Guest D. If Guest D pays it back to Guest C, who pays it back to Guest B pays Guest A, the £1 is said to have done £4’s worth of work. The bookkeeping of this transaction shows that £1 was lent out 4 times and they all cancel each other out! Just to be clear, £1 has done £1’s work and not £4’s work. No real wealth or value is created.

The velocity of circulation makes no economic sense.

Error Three — the general price level

Since the monetary authorities have no means to sum the price and quantity of every individual transaction, they must work instead with the “general price level”, ignoring the vital role of changes in relative prices.

As early as 1912, Ludwig von Mises demonstrated that new money must change the structure of relative prices. As anyone who has lived through the past year could tell you, new money is not distributed equally to everyone in the economy. It is injected over time and in specific locations: new money redistributes income to those who receive it first. This redistribution of income not only alters people’s subjective perception of value, it also alters their weight in the marketplace. These factors can only lead to changes in the structure of relative prices.

Mainstream economists believe that “money is neutral in the long run”. They do not have a theory of the capital structure of production which can account for the effects of time and relative prices. They believe increases in the money supply affect all sectors uniformly and proportionately. This is manifestly untrue: look at changes in the Bank of England’s balance sheet and your bank statement.

Hayek wrote that his chief objection to this theory was that it paid attention only to the general price level and not to the structure of relative prices. He indicated that, in consequence, it disregarded the most harmful effects of increasing the money supply: the misdirection of resources and specifically unemployment. Furthermore, this wilful ignorance of relative prices explains the mainstream’s lack of an adequate theory of business cycles, something Hayek provided.

The general price level aggregates away a vital factor: the relative structure of prices.

Error Four — the aggregate quantities of goods and services sold

Since the sum of price times quantity for every individual transaction is not available, the authorities must use the “aggregate quantity of goods and services sold”. This is nonsense: the quantities to be added together are incompatible. It makes no sense to add a kilogram of potatoes to a kilogram of copper to a litre of petrol to a day’s software consultancy to a 30-second television advert.

The aggregate quantity of goods and services sold is an impossible sum.

Error Five — the equation is no more than a tautology

Consider this, if I buy 10 copies of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations from a printing company for 7 monetary units (or MU), an exchange has been made: I gave up 7 MU’s to the printer, and the printer transferred 10 sets of printed works to me. The error that the mainstream make is that “10 sets of printed works have been regarded as equal to 7 MU, and this fact may be expressed thus: 7 MU = 10 printed works multiplied by 0.7 MU per set of printed works.” But equality is not self-evident.

There is never any equality of values on the part of the two participants in exchange. The assumption that an exchange presumes some sort of equality has been a delusion of economic theory for many centuries. We only exchange if each party thinks he is getting something of greater value from the other party than he has already. If there was equality in value, no exchange would happen! Value is subjective and utility is marginal: each party values the other’s goods or services more highly than their own.

Thus, while the mainstream believe that there is a causal link between the “money side” of the equation and the “value of goods and services side”, it is just a tautology from which no economic knowledge can be gained. All we are saying, if the Quantity Theory holds, is that “7 MU’s = 10 sets of printed works X 0.7 MU’s per set of printed works”: in other words, “7 MU = 7 MU”. Thus what is paid is what is received. This is like announcing to the world that you have discovered the fabulous fact that 2=2.

The mechanistic Quantity Theory of Money is not a causal relation but a tautology.

Conclusion

The mechanistic Quantity Theory only provides us with a tautology and every term of “MV = PT” is seriously flawed. Public policy should not rest on the foundation of this bad science.

If the money supply contracts as it has done so spectacularly since late 2008 (see the chart above), you will have less goods and services supporting less economic activity. This for sure is bad. We now have less money and less exchanging of real goods and services for other real goods and services.

The only way to get more goods and services offered for exchange is if entrepreneurs get hold of their factors of production — land, labour and capital — and reorganise them to meet the new demands of the consumers in a more efficient way than before. The only thing that the government can do is to make sure it provides as little regulatory burden as possible and the lightest tax regime that it can run in order to allow entrepreneurs to facilitate this correction.

Certainly in my business of the supply of fish and meat to the food service sector — www.directseafoods.co.uk — I have never witnessed such an abrupt change in consumption patterns as people have traded down from more expensive species and cuts to less expensive ones. Thus I have to reorganise my offer to my customers and potential customers. No amount of fiddling about with the level of newly minted money in the economy will help this reorganisation of my factors of production: they need to be retuned to the new needs and desires of my customers.

Quantitative easing, as I have said before, is firmly based on a belief in the so called “internal truths” held in the Quantity Theory of Money. I hope any reader can see that this belief is based on very faulty logic. Bad logic gives us bad policy. A policy of QE says that because the velocity of circulation has fallen, we can print newly minted money, out of thin air, at the touch of a computer key, and create more demand for the exchange of goods and services.

Money has been historically rooted in gold and silver because these cannot “vanish” overnight as we are seeing under our present state monopoly of money — fiat money, money by decree, i.e. bits of paper we are forced to use as legal tender. Remember, since 1971 when Nixon broke the gold link, money is just bits of paper, notwithstanding a promise to pay the bearer on demand. In the near future, this will no doubt remain the case. Indeed, anyone who dares to mention that the final good, for which all goods exchange, should be a real good that is scarce (hard to manipulate it, hard to destroy it) unlike paper and electronic journal entries (easy to manipulate, easy to destroy) is considered a lunatic!

On a point of history, it is worthwhile remembering that, as we have mentioned here, the 1844 Peel Act did remove the banks’ practice of issuing promissory notes (paper money) over and above their reserves of gold (the most marketable commodity i.e. money) as this was causing bank runs, “panic”, boom and bust. They did not resolve the issues of demand deposits to be drawn by cheque. Both features allow banks to issue new money — i.e. certificates that have no prior production of useful economic activity such as our printer printing books or my selling of meat and fish — while retaining real money — claims to the printing of books and selling of my meat and fish — only to a percentage of the deposited money, i.e. the Reserve Requirement of the bank. In the UK, there is no Reserve Requirement anymore as far as I am aware, hence banks going for massive levels of leverage. It is no surprise that the house of cards has fallen down.

Our proposal for a 100% reserve requirement is offered for discussion as the only sure-fire way of delivering lasting stability. Listening to economists talking about the “velocity of circulation” falling and thus suggesting that we should conduct large scale Quantitative Easing to hold the price level is not economics, but the policy of the Witch Doctor and the Mystic.

It is staggering that so much garbage, posing as sound knowledge, hinges on these grave errors.

Further reading

- Huerta de Soto, Money, Bank Credit and Economic Cycles, pp 522-535

- Prices and Production and Other Works, F A Hayek, esp pp 197-222 “Theories of the Influence of Money on Prices”

- Bank of England Increases Size of Asset Purchase Programme by £50 Billion and linked articles

I am not an economist, but a student of economics. I am however, a chartered aerospace engineer, so I hope I know something about the positive application of science.

I know for example that the flight of an aeroplane can be accurately controlled by moving various control surfaces, that a gas turbine responds in a highly predictable way to changes in the rate of fuelling and that the combination of inertial navigation, GPS and terrain profile matching gives an accurate and reliable position. These are examples of positive applied science, examples which rely on systems and equations which are causal, verifiable and refutable. They do not aggregate out vital information.

Hayek introduces Prices and Production Lecture 1: Theories of the Influence of Money on Prices (download) with Cantillon’s remarks on Locke:

And yet we find modern policy makers still ignore relative prices in their justification of the monetization of the deficit. Hayek goes on:

And vitally (emphasis mine):

As a student of economics, it appears that we made not just little progress from Cantillon to Hayek, but that, in this regard, we have made little progress since. I urge interested parties to read, with an open mind, both Hayek and de Soto, which are available to download free through those links.

The What is Money? link is broken: 404, not found. The article is also available here.

Thanks Sam. Missing redirect. Should now be fixed.

Toby Baxendale,

I am sorry to say this, because I like the Cobden Centre and its goals, but this article is very confised about the equation of exchange, what a tautology is, and about many other things. I do not have time to address all of the errors (perhaps I will on my blog sometime).

Toby writes:

No, no, no, and then no again. I can’t stress that enough. If A and B exchange an apple for money repeatedly, the same apple for the same money, then the average price of all these transactions is equal to the money exchanged in any one particular transation. In other words, “P” remains constant while “T” increases. Any increase in “V” is exactly offset by an increase in “T”, while the money supply and price level are unchanged.

Monetary disequilibrium occurs when either “MV > PT” or “MV PT”, then either “MV” must decrease or “PT” must increase to restablish equilibrium. Let me quote F.A. Hayek on the matter:

By the way, it’s “quantitative” and not “quantative”.

Isn’t velocity the equivalent of the demand for money? Demand for money can change in Austrian theory and so offset the price impact of an increase in the money supply. Hence I have always assumed that that was what the mainstream was getting at when they refer to changes in velocity. Whats the difference?

Yes, that’s right. Velocity is the inverse of the demand for money to hold across the entire economy.

In many ways the Cambridge equation:

M = k P T

… is clearer. In this case k is the demand for money across the whole economy. (Notice this isn’t a marginal demand).

I may post about this some more if I have the time.

Please do. If you have time.

Quantitive Easing, is, assuming the Government does not borrow the money from the banks (which it does not need to do), one of the few options to kick start the ecomony and slow down the devastating effect of recession and unemployment. Of course it is inflationary but the Banks create over 200Bn sterling of new money (in debt)every year!Surely it is better to allow the Government to invest in infrastructure and services of value to the country than allow the banks to continue with their legal forgery.This is the fundamental issue to be addressed and rather overshadows the detail behind the equation MV=PT. A solution to the problem of our monetary chaos can be found on http://www.legalforgery.com/.

What you’re proposing is “tax and spend”, but using inflationary stealth taxation rather than ‘honest’ taxation.

“Tax and spend” is seriously misguided; “stealth tax and spend” is deeply immoral (for that matter, so is “borrow and spend”).

The banks should not have the power to expand the money supply, but neither should the government. If there is fiat currency, expansion of the money supply should require a referendum, and everyone should be clear about who receives the new money.

It would still be theft, even if voted for by a majority, but at least it would be out in the open.

Sorry Bob, I do not understand. How do new money units, created from nothing , create more goods and services (wealth) ? Please explain.

I’m not really sure to what extent I disagree with Toby. Anyway, I’ll write a few comments about the subject here….

The money quantity equation MV=PT is a rare and delicate flower, I’m tired of people questioning her honour. She is an identity, which is not quite a tautology but close. MV=PT is an equation that is true by definition so long as the terms it contains are clearly meaningful.

The beauty of this identity is that it makes things clearer to a person once they understand it. Things that are tautologies and identities should not be cast aside as useless because they are simply the consequences of logic. There is much that we can learn by studying them, this is especially true in economics since the complexities of normal language have complicated understanding of simple things, with logic we can eliminate that complication. This is similar to the argument that Mises makes for “Praxeology” and part of it. MV=PT is essentially Praxeology.

To build any substantial economic theory though we need more than logic, we need statements about the economic world. Mises called these “Catallatics”. It’s when these messy ideas about the world are joined with the elegant money quantity equation that confusion takes root. Many schools of economics have taken the money quantity equation as their own, they’ve implied that they’ve married it and made it their own. But, this is just an illusion. Theories about the elements of the money quantity equation are Catallatics. Once these theories are combines with the equation an overall theory is produced.

So, we have:

t = Period of time under consideration.

M = Quantity of money circulating in a period of time t.

V = Number of times a unit of money is transacted per period.

P = The set of price of goods, assets and services exchanges against the money unit.

T = Total transactions made for the things mentioned above.

MV = PT

The equation becomes more clear if it is broken up…

Let’s suppose that in a period t eight apples and nine pears were traded. The pears were traded for 1 money unit and the apples for 2 and lets suppose 20 money units were in circulation.

MV = PT

MV = price_pears * pears + price_apples * apples

40 * V = 2 * 8 + 1 * 9

V = 0.625

The equation doesn’t concern itself about whether the apples and pears were newly produced, or already existing. It doesn’t say anything about production. It doesn’t even say if one pear is traded nine times, or if nine pears are traded once. As Lee Kelly mentions above the example Toby gives of exchanging a house several times is wrong. It’s important to notice that P in is “price level” of all things transacted, not just goods and services but also capital goods, land, assets such as shares and second hand goods. It’s also important to notice too that there is a very similar equation often written MV=PQ which related to GDP output Q. That equation is quite different the V, P and Q variables all have different meanings.

If we pick a small time period where no money unit is used more than once then the term V is simply the proportion of money units that are used in the period.

If people decide to hold larger stocks of money then V falls. As I said above, V is inversely proportional to the accepted demand for money to hold. In the above example the people in that economy overall hold 15 money unit and trade with the remaining 25. If some of them wanted to hold more money and succeeded in doing so then V would decrease correspondingly.

For this reason the equation can be written in the alternative “Cambridge” form:

M = kPT

Where k is proportional to the accepted demand for money to hold.

Toby mentions that in his view you cannot add up quantities that are incompatible. It’s true that this is a troublesome. What economists have often meant, though they have often being very unclear about it, is that “PT” is a vector multiply. As in my example above, the price of pears is multiplied by the number of pears traded, and the price of apples by the number of apples. Then, those totals are added together. Though apples and pears are incompatible quantities the sums of money spent on each of them are compatible quantities.

I still haven’t linked to this any theory. All of the letters M,V,P,T,k that I’ve used above are at this stage variables. There are many theories that it can be connected with.

Toby mentions the idea that the variables represent “values” of some sort. Mainstream economists certainly do not hold this view. A few people have been stupid enough to hold this view and Toby’s criticisms of it are quite correct.

What Mises called the “mechanical quantity theory” is one of the oldest. Proponents of the traditional form of this theory suggest that the demand for money k or the velocity V doesn’t change, and that the prices of all goods are modulated by the amount of money. The two parts of that theory are quite different.

M = k(price_pears * pears + price_apples * apples)

A proponent of the old mechanical quantity theory would say that if M were doubled then the price of pears and the price of apples would both double. They would say that there is a proportion, an exchange ratio or “relative price”, between apples and pears that a rise of fall in the amount of money wouldn’t change it. This theory is sometimes called the veil of money.

In “The Theory of Money and Credit” Mises explains in some detail why this view is wrong. When new money is created, or old money is destroyed, that process doesn’t happen evenly across the whole economy. It happens in particular markets first. Toby describes this issue of money injection well above. So, money is “non neutral”.

“Non neutrality” is closely related to sticky prices and account falsification. If prices are sticky then money isn’t a veil, it has real effects on output. If account falsification occurs then the result is the same.

The second part of the theory says that k or V are constants or roughly constant. Modern monetarists don’t hold the view that money is a veil, but they often support the view that V is roughly constant. They offer charts of V in evidence of this, but often those charts relate to the different equation MV=PQ, and they show quite significant variations anyway.

But, it’s important not to conflate these mistakes with the MV=PT equation itself. If k isn’t a constant it can still be incorporate into the equation as a variable.

The different theory that “money is neutral in the long run” is more complicated. To make it really meaningful we must know what the “long run” is, it’s more reasonable for some meanings of the term “long run” than others. But, it suffers from two problems that are highlighted by Austrian and Keynesian economists. Austrian economists would point out that since money isn’t injected neutrally it will cause relative price changes. Those changes will cause decisions on investment/capital good production to be changed and affect the future economy for the rest of time. Just because prices are not sticky in the long-run doesn’t mean that money is neutral in the long run, since short run price differences have permanent consequences. So, short run non-neutrality implies long-run non-neutrality. Some Keynesians reach the same conclusion by a more contorted route, they say that since monetary changes may cause unemployment that could cause different amounts of investment which would have long term effects.

None of these problems with mechanical quantity theory and Monetarism demonstrate that quantity of money M should be kept constant. It doesn’t follow that just because V isn’t constant that Rothbard and his 100% reserve theory is right. It’s also wrong to think that just because reorganization is needed in a recession that this shows that changing the quantity of money can’t also be useful.

I generally agree with those who propose creating money in recessions. They have a theory that uses the quantity equation too. Evidence has shown that demand for money rises when people are uncertain about the future. This isn’t surprising as the main economic purpose that holding a stock of money supplies is a fund that can be used immediately on any purchase. As I mentioned above prices are sticky to some degree. When money is withdrawn from the economy in various places by people increasing their money holdings and no extra money is created the equation M=kPT tells us that PT must fall. The prices that make up P are sticky, so it cannot fall quickly or uniformly. And account falsification occurs as they fall just as it does as they rise. As a result, there is a fall in T as well as in P. In any economy where most of the constituent of T are wealth creating transactions that means we have a recession. This is the “secondary recession” or “Keynesian type recession”.

In this case creation of money brings us the possibility of leaving T roughly unaffected. It prevents the problems of price adjustments from causing real losses. To put it another way, what creation of new money can produce is prevention of real adjustment costs. This theory is just the inverse of the ABCT theory of the boom.

But, all that doesn’t mean I’m happy about Quantitative Easing. The Bank of England have no idea what the real demand for money is or the real cost of supply. The banking system eats up that information before it ever gets to the BoE. They have no idea how much money to create or how to create it in the right places where the shortages exist. They can observe CPI or Nominal GDP, but those measures only relate to transactions of output or GDP goods, not directly to the demand to hold money. For political reasons the BoE are very likely to overshoot, create too much money and create inflation and ABCT later.

To current:

You put forward an argument for money pumping in a down turn as prices are sticky going down. You then refute it yourself in your last para.

I suggest you bin your ideas on this.

Identities are useful. 2+2=4 is useful. The problem is that some people think they can get more out of the tautology / identity than the sum of its parts. That is the subject of my article.

I will add, in a down turn, the only thing that will correct the down turn, yes when money demand has risen, is not to mess about with the supply base of money, but let the businessmen adjust costs down in a greater amount than the fall in transactions, the inverse of the money demand going up. This readjusting of the cost base and a protection of profits, is the only way to give people that comfort to readjust that money demand back again. No messing about by the state can fix this. This will lead to more account falisifications , end of story.

> You put forward an argument for money pumping in a down turn as

> prices are sticky going down. You then refute it yourself in your

> last para.

I agree with monetary expansion in recessions as an “ideal policy” assuming the right institutional conditions, such as free banking. My last paragraph is about our situation now with what we have in practice. I think central banks can’t be trusted with quantitative easing.

> Identities are useful. 2+2=4 is useful. The problem is that some

> people think they can get more out of the tautology / identity

> than the sum of its parts. That is the subject of my article.

I agree with you to some extent about that. The real issue is the theories that are applied to the equation of exchange are confused with properties of the equation itself. But, that doesn’t mean that we should abandon the equation which is useful for discussion.

> I will add, in a down turn, the only thing that will correct the

> down turn, yes when money demand has risen, is not to mess about

> with the supply base of money, but let the businessmen adjust costs

> down in a greater amount than the fall in transactions, the inverse

> of the money demand going up. This readjusting of the cost base and

> a protection of profits, is the only way to give people that

> comfort to readjust that money demand back again. No messing about

> by the state can fix this. This will lead to more account

> falisifications , end of story.

Monetary expansion can be useful, if its done by the state it’s likely not to be but as a general principle it can be useful.

I’ll give a toy example… Let’s suppose that we have a economy using a 100% gold standard. Suppose that at the beginning there are 30lbs of gold in circulation as money. For some external reason there is a shock and some people raise their demand for money. If there is no change in the supply of money then the only way that this can be achieved is by prices adjusting downwards. However, though prices adjust they cannot adjust quickly. This results in the problems of deflation. Just as with a monetary injection the effects of an increase in holding will spread outward from those people who decrease spending. As it does so demand falls in various markets and because prices aren’t perfectly and instantly flexible they don’t adjust downwards quickly enough to keep output and employment from falling. During this process account falsification occurs in the negative direction. Profits reported are lower than actual profits and losses are heavier than actual losses. This is the corollary of the opposite effect that occurs when there is an injection of money. Eventually prices do adjust and as that happens there is a return to normality. However, if the original shock was only temporary and the demand for money it created subsides later then prices will rise and the problems of inflation will occur.

That’s the situation with no money creation. Suppose alternatively that there is a large quantity of gold jewellery in the economy and the means to work it cheaply. In that case once the purchasing power of money rose beyond a particular threshold it would be profitable for people to coin their jewellery into money. Doing that stabilises the purchasing power of money to some degree and prevents economic calculation from being impaired. Then if the demand for money falls later then it will become profitable to melt the extra coins down again and turn them into jewellery again. If the gold market can do this faster than prices can change then they can prevent the adjustment costs of deflation. (The jewellery market probably can’t act that fast I only use this example to illustrate that the general principle).

In another reply you write:

> Any level of money will suffice to have a functioning economy.

…

> We only create wealth when entrepreneurs use factors of production

> better to make goods and services more in demand and supplied at

> better prices and served up in better ways for the customer.

>

> No amount of new money units from whoever can make this happen.

It’s important not to confuse the long run with the short run. I agree that all this is true in the long run. Any amount of money suffices in the long run, but in the short run changes it the amount cause real effects.

Creation of new money, and destruction of money too in other circumstances can avert the adjustment costs that would be associated with fluctuations in purchasing power.

Your toy e.g. I think is wrong as all my 20 years of work tell me prices do respond very quickly. Even wages. 10% paycuts were the norm in my business for people earning over £50k PA post Lehman and it happened over night. Prices can and do adjust in crisis.

Money creation in a FRFB world is always counterfeit if issued over and above the physical thing that backs it. Therefore I propose no money accomodation and just let the market do what it does best: allocate resources.

Gold backed money can’t be destroyed, so we can’t worry ourselves with a money deflation in a FB world.

> Your toy e.g. I think is wrong as all my 20 years of work tell

> me prices do respond very quickly. Even wages. 10% paycuts were

> the norm in my business for people earning over £50k PA post

> Lehman and it happened over night. Prices can and do adjust in

> crisis.

In that case why is ABCT a problem?

The question is whether prices are transmitted quickly across the economy. If they are then not only would there be no secondary recessions there would be no ABCT booms and busts. Because, as new money is created that money would bid up prices in asset markets, the higher-order goods, which would spread quickly through the economy raising the price of consumer goods, the low order goods.

To be consistent there must be stickiness in both upward and downward directions. Not necessarily similar stickiness, but stickiness all the same. I don’t think it’s plausible to say that prices are sticky upwards but very flexible downwards.

> Money creation in a FRFB world is always counterfeit if issued

> over and above the physical thing that backs it.

If a bank’s customers agree to accept fiduciary media that is a debt then that’s something that they can do, there is no dishonesty in it. The dishonesty only comes into play if the bank don’t disclose that situation, if the bank pretends that the contract is a bailment.

If there were Free banking and consumers decided to use 100% reserve bailment accounts and notes then the FRFB side would not complain. It’s up to the two parties who make a contract to decide how much they trust each other. But, we think that it’s overwhelmingly likely that if there were Free banking then consumers would choose fractional reserve banking, that’s what’s happened in the past.

> Gold backed money can’t be destroyed, so we can’t worry

> ourselves with a money deflation in a FB world.

It can be melted down and turned into other gold products. If that happens then it ceases to be money.

To Toby

Cutting government expenditure or raising taxation seems essential in order to reduce the amount the government borrows. The shortfall is about £170 billion a year at present (early 2010).

Unfortunately, cutting government expenditure means cutting jobs and even though a very large number of government jobs are unproductive and some are clearly a hindrance to the private sector, the loss of these jobs would raise the level of unemployment. Any increase in unemployment changes people paying taxes into people drawing unemployment benefit. Higher unemployment also reduces demand for goods and services which further increases unemployment in the private sector.

Raising tax levels also reduces demand for goods and services which causes a drop in private sector employment, but does not directly cause a loss of government jobs.

You might conclude that raising taxes is less harmful than cutting government expenditure but higher taxes are very damaging to private sector business and it is only the private sector that really supports the whole economy.

If only the government understood that if private banks were prevented from creating new money the State could create it instead. In 2007, the last year before the banking system imploded it created (forged) about £177 Billion of new money as deposits and considerably more as loans. A lot of this new money went towards raising house prices and even more unproductive speculative activities, but if the private creation of new money was stopped a large part of it could be replaced by government created money.

The amount of new money the government could create in the next year without causing overheating would be at least equal to the £200 Billion created by the Bank of England as “Quantitative Easing” in 2009, but would not be used simply for buying existing gilt edged securities, it should be used to maximise the growth of private industry by making low interest loans and for spending on infrastructure. The best way of increasing demand would be to raise the basic income tax allowance to about £20,000 a year.

All of this completely depends on stopping the private banks from lending more money than they take in as deposits. The method used for preventing the private banks from doing this is open to debate but it is surely possible and the benefits that would flow from it are enormous.

“Unfortunately, cutting government expenditure means cutting jobs and even though a very large number of government jobs are unproductive and some are clearly a hindrance to the private sector, the loss of these jobs would raise the level of unemployment. Any increase in unemployment changes people paying taxes into people drawing unemployment benefit”

People employed by the government don’t really pay tax. They are net beneficiaries of confiscated wealth. Even with our overly generous benefits system, paying redundant government employees benefits would almost certainly be cheaper than paying them to do useless jobs.

As for the reduced spending power of these ex public sector workers, and the possible impact on the wider economy, always remember that whenever the government spends or borrows, it does so at the expense of the private sector (which could otherwise be doing the spending or borrowing). To the extent that the private sector spends less freely than government, it is probably wise to do so.

It is true that some areas will suffer more than others from cuts to government, but that is simply because some areas have disproportionately benefited from government largesse. The readjustment may be painful, but it is necessary.

Bob, whilst there is much I agree with in what you say, there is much I do not.

No one should create money.

Any level of money will suffice to have a functioning economy. Increases in productivity (the aim of all capitalists), all things being equal means more goods and services and thus more wealth. The purchasing power of money goes up. Prices go down.

We only create wealth when entrepreneurs use factors of production better to make goods and services more in demand and supplied at better prices and served up in better ways for the customer.

No amount of new money units from whoever can make this happen.

Less of the state feeding off the tax payer will allow more money to be kept by entrepreneurs in their business to do just what they set out to do, create more wealth.

Government needs to get out the way end of.

The government with its private sectors mints , aka the banking system needs to be totally returned from whence it came : the private sector.

Just as I do not trust the government to set the price of apples or heating, I do not trust it with government, but I do trust the free unhampered interplay of 60 million people trading peacefully together to work out what they do and do not need.

Thank you for your comments.

To Bob Davies,

I don’t think the loss of government jobs is a problem and the clue is contained in part of what you said: “a very large number of government jobs are unproductive”. I would suggest that if these jobs are unproductive perhaps they shouldn’t be doing them in the first place. Paying people to waste time and resources might be worse than paying them to do nothing (unemployment benefit) in my view.

Further, I would argue that the only true tax cut is a cut in government expenditure since all government expenditure is ultimately financed by taxes, hidden or otherwise. I would suggest that the government providing jobs may on the surface appear to be a good thing but what is not seen are the jobs that would have been created by the private sector in the absence of these government jobs! This is because the government bids up the price of the factors (materials and labour) that the private sector would have used for productive processes and uses them for unproductive purposes instead. Ultimately, this would lead to a greater loss of jobs in the private sector than are gained in the public sector.

In common with most commentators those contributing here are falling into the same pit of confusion that has been the bain of economic reformers for the past few centuries.

Why is it that such a simple concept can evoke such passion?

It is the mechanism used to create ‘money’ that also creates the problems around the mechanics of the economy.

When virtually all economic activity is dependent, as it is currently, on a foundation of ever expanding levels of debt based purchasing power/capital the outcomes will be determined not by the forces of the seller/purchaser market but by the entities who own and operate the debt as money mechanism.

Until the debt as money mechanism is addressed no amount of debate over the mechanics of economic activity will lead to a long term resolution of the issues around production, distributon and consumption. End of story!