In an illuminating and fascinating 30-minute interview, I spoke tonight to Professor Gerard Casey about the current economic and political situation in Ireland, mixing in Aristotle, St. Thomas Aquinas, and the fall of the Western Roman Empire along the way, for good measure, just so we could get a complete picture.

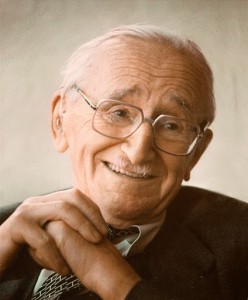

Professor Casey is a member of the School of Philosophy in University College Dublin and also an Adjunct Scholar at the Ludwig von Mises Institute, in Auburn, Alabama, in the United States:

Great interview, thanks!

Speaking of Aristotle and Aquinas, to-day’s Mises Daily contributions include Professor Casey on ‘The Major Contributions of the Scholastics to Economics’.

In the interview, Professor Casey notes that the Reformation (and its accompanying religious animosities) may account for the reason why the Protestant ‘North’ was not cognisant of (or ignored) the economic writings of the Catholic ‘South’ with respect to subjective utility. The result was that the Scholastic discoveries in economics remained hidden from the North until the work of Cantillon, Adam Smith, &c.

Yet what happened to economic thought in the South after the waning of the School of Salamanca? For the lay reader in Austrian economics—or perhaps, more appropriately, in the School of Subjective Utility—there seems to be a void in the economic theorising of the South until the work was taken up again by Menger. Did Mercantilist thought come to infect the South, too? Or are we awaiting further research on economic innovations in Italy and France during this time?

(As an aside, for more on Scholastic economic insight—in addition to the references in Casey’s ‘The Major Contributions of the Scholastics to Economics’—may I suggest Jerzy Strzelecki’s ‘The School of Salamanca Saw This Coming’, Lew Rockwell’s ‘The World of Salamanca’, and Jesús Huerta de Soto’s ‘Four Hundred Years of Dynamic Efficiency’.)

Rothbard’s Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic thought discusses what happened after Scholastics. Scholastics did continue well in to the 17th century and I think the thought did take roots to a degree in the Netherlands at least.

http://mises.org/books/histofthought1.pdf

He blames the scholastics for holding on to anti-usury thought. The “political application of religious principles” (p. 128) and ” ‘casuistry’: that is, of applying moral principles, both natural and divine, to concrete problems of daily life.” couldn’t have made them popular with the rising state. Rising humanism seemed actually quite pro-statist (human can follow their own laws not gods.) He also believes the Protestant and cypto-protestant Jansenist, etc. rejection of the Catholic idea that reason can and must correspond with faith downgraded the scholastics, and other rejection of the Thomist joining of the rational and empirical. Then there was the general breakdown of Christendom with a common latin language and common universal church. He doesn’t explain further why the universities were less important, but they were. Probably the secularization of society and breakdown of the old order.