In his recent Congressional testimony, our dangerous monetary Dr. Moreau was forthright in defence of his latest wild experiment in inflationism, saying that the rate of the fall in the value of people’s money was “expected to persist below the levels that Federal Reserve policymakers have judged to be consistent with their mandate.”

Obviously, the Chairman has not been to the gas station recently, nor has he popped out to the supermarket to restock his larder, or he might have noticed that, as AP reported at about the time he was speaking, “Some food makers… began selectively raising prices within the past few quarters. Those higher prices have begun filtering into stores. Supermarkets have resisted price increases for some time, hoping to hold onto their cost-conscious customers in the tough economy. But chains such as Kroger now also say higher prices are coming…”

As the article goes on to note, such notables as Kellogg, Sara Lee, Smucker, Tyson Foods, and McDonalds are well on the way to taking steps to defend their margins with overt price rises while many companies have already moved to disguise the adjustment by changing portion sizes or switching to lower grade ingredients.

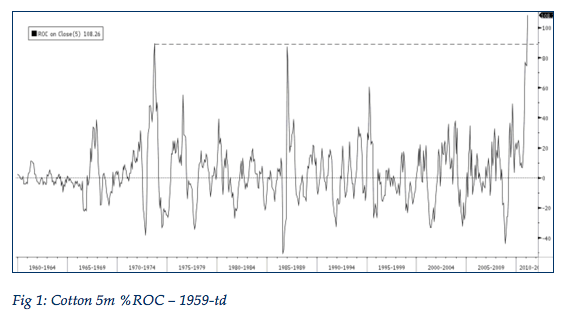

Cotton prices have, meanwhile, more than doubled in the past 5 months – potentially pushing up apparel costs across the board – an escalation which has not been seen in a like period for at least half a century.

While Bernanke is trying to blame such inconveniences on demand in the emerging markets (without inquiring too closely into what it is that such demand is predicated upon), the disinterested observer might note that it is not entirely a coincidence that this latest resurgence has occurred as he and his colleagues have done their best to make good on the cart-before-the-horse, Jackson Hole doctrine of raising inflation expectations in order to lower hypothetical real yields in some corner of the de Wittian multiverse (incidentally, a source of obvious contradiction when he now attempts to deflect his critics with the claim that such expectations have remained gratifyingly ‘stable’)

Indeed, as the next figure shows, the rate of increase of proper (Austrian) money supply this past semester is in excess of trend to its greatest degree since the immediate LEH-AIG core meltdown SCRAM, and lies in the 96th percentile of the last three decades’ range.

Moreover, as the graph appended in large format at the end of this article makes plain, the implementation of QE-II via the programme of buying Treasury bonds has been mirrored in a surge in commodity prices no less strikingly than did their rebound from the post-Crash lows correspond to the launch of QE-I.

But, as one TV anchor challenged me earlier this week, “isn’t a little bit of inflation a price worth paying for an increase in employment” to which the answer is unequivocally, “No!”, not least because of the eternal temptation to try to avoid ever paying it.

More fundamentally, this whole issue of using monetary and fiscal ‘stimulus’ to repair a slump which has been typically brought about through previous, ill-judged attempts to steer ‘policy’ has at its heart a dirty little secret. Because of the entrenched factional interests of the Entitlement State – often, but not always, reinforced by labour union militancy – the same Fabian elite whose bankrupt, Tooth Fairy wishfulness has cost far too many souls their livelihoods perennially despairs of anyone ever regaining employment by facing up to the tough but inescapable fact that the man giving them a job has to earn his living, too.

Thus our leaders routinely quail before the political and presentational difficulties of telling those who have misleadingly become accustomed to a better standard of living in the Boom than their input into the productive process actually merits that they must now face a less comfortable reality and temporarily accept less reward for more effort while the economic structure reorders itself in a more sustainable fashion.

Ultimately, the so-called Keynesian miracle is based on the shallow deceit that if Mohammed will not go to the mountain of lower unit, nominal wages, the mountain must be transported to Mohammed using the machinery of inflation to reduce the real value of those same wages.

The only problem with this nostrum is that it fails – in typical aggregationist fashion – to see that what counts for each individual employer (the idiosyncratic human atom who helps constitute the featureless, mathematical abstraction called ‘employment’) is that the monetary value of the sales of his particular goods or services must rise faster than the sums he expends on the workers who give rise to them – i.e., that the value of their marginal product exceeds once more their marginal cost, or else there is no point hiring them.

Even that is not the end of the story, for our businessman also needs to pay for all the other inputs which go into his endeavour – raw materials, plant, equipment, components, capital means, rent, taxes, and levies such as mandatory health-care, carbon taxes, unemployment ‘insurance’, and pension contributions (the last, you will notice, thoroughly amenable to alleviating political action of a far more beneficial kind).

It should be obvious that, once the authorities begin monkeying with the volume of money in the system, it rapidly becomes almost a matter of happenstance that any one company finds itself in the favourable position that its costs will inflate more slowly than its revenues. It should be even more apparent that it is an outright impossibility that this can be the case for everyone, all at once [see the succeeding figure for a very broad brush illustration in the case of the UK].

Further complications arise from the consideration that the very fact there has been a Bust proves that an inordinate number of people had previously been lured by the economy-wide Ponzi scheme of the Boom into lines of work which have now been shown to be either sub-marginal, or completely unviable. Part of the reason for this is that the Boom has introduced a progressively wider and more pervasive disparity between what people do to acquire their own purchasing power and what they choose to spend it on (whether that takes the form of end-goods or debt service payments).

Given this reality, what do you suppose are the chances that the renewed inflationary tide will not only lift all boats equally – that there will somehow arise absolutely no differential injection, or Cantillon, effects – but that it will preferentially refloat the seabed wrecks of those which have foundered amid the Bust and so miraculously restore employment and income levels to their former, febrile heights?

Beyond even this, a further malign feature of inflation is that it makes the reading of the underlying balance of supply and demand – not just for specific goods, but for all goods in their ever-shifting, near-infinite matrix of interrelations – even more difficult than usual because it corrupts the signals inherent in their relative, even more than in their absolute, prices.

Think of the transmission of money in the act of exchange as the sending of a communiqué describing some essential features of what took place in that transaction and why. Now imagine that the text of the message is arbitrarily and unpredictably altered – sometimes with the addition of characters, sometimes with their deletion – and also that the time taken to deliver such missives is expanding and contracting in what may be a quasi-random fashion.

Contemplate the difficulties which also arise because of the time-varying nature of the inflation. Because the inflation is an extraneous act of political will (or financial caprice) – and so is subject to sudden stops, starts, and redirections – it represents a dangerous aggravation of the normal entrepreneurial hazards inherent in organizing profitable production into an uncertain future in a constantly-evolving economy.

At the very least, this confusion should serve to heighten actual business risk even if ostensible risk premia are being artificially suppressed by the weight of new money acting on the financial market – a combination which is all too likely to lead an entirely new fleet of White Star liners onto the rocks of the inevitable Bust to come.

Who’s to blame for rising prices?

If there is not yet much hope that an inveterate ‘output gapologist’ like Mr. Bernanke – or, for that matter, Mr. King – will be persuaded of the foregoing, there are clear signs that – somewhat belatedly, perhaps – some of those in office in the emerging market power houses have begun to waken to their peril.

In Brazil, official rates have been raised four times for a total of 250bps and there is a great deal of expectation that another 50bps is in the pipeline. India, for its part, has moved the repo rate up in seven stages for a cumulative 175bps with, again, another 50bps thought likely to materialize over the next couple of months. China, of course, has so far only managed to steel itself to deliver three hikes of 25bps in an interval in which the annual CPI change could well have accelerated more than three times as fast.

That said, the latest editorial in the official People’s Daily mouthpiece was fairly uncompromising on the interpretation which it hoped would be put upon the latest of these rises.

To sustain sound and stable economic growth, Chinese policy-makers must take more measures to prevent inflation from escalating further… The timing of the announcement, at the very end of the lunar New Year holiday, displays an extraordinary sense of urgency. Had the pressure of accelerating inflation not been so huge, Chinese central bank officials would not have needed to break their holiday to take action…

Just in case we were in any doubt of his inflationary intent, Chairman Bernanke had the gall to express an open disapproval of the move – branding it as ‘surprising’. Given that he blames China for rising food prices, this may seem just a little too cute, but his incoherence was only compounded by his remarks that instead of interest rates, the Chinese should revalue the currency and so redirect exports to meet internal demand.

Well, over the long run, that does makes sense for the ordinary Chinese, but it completely misses one or two obvious, interim objections, namely that: (a) since capital and labour is heterogeneous, Ben – as we discussed above – a painless reallocation would be impossible to engineer outside of a Harvard eco department spreadsheet and (b) even if, by some miracle, domestic consumers did manage to take up all the redirected, former export goods (and at a profitable price for their makers), pressure on world resources would hardly abated by the cessation of Chinese saving this involved (however inequitably ‘forced’ much of this may currently be).

For their part, the Chinese were quick to shoot back at their decrier that:-

In addition to such domestic factors as rising food prices and labour costs, the super-loose monetary policies that major developed economies have adopted to inflate their way out of recession are also undermining the country’s efforts to curb inflation by driving a large amount of capital flows into emerging economies including China.

…[Bernanke’s] remarks indicate that the United States is far from even recognizing the danger of too much cheap money, which, to a certain extent, led the world into the worst global financial crisis in more than 70 years in the first place, and now threatens to fuel runaway inflation in many emerging economies.

What a funny old world it is: all this ‘imported’ inflation everywhere we look and, seemingly no-one to be found anywhere who is actually responsible for ‘exporting’ it.

A Chinese revaluation would be just the ticket, wouldn’t it?

Reduce the cost of imports into China, including food whilst increasing the price of goods sold by China to the West.

The West may gain from increasing exports but it would lose by having to pay it’s workers more or, allow the living standards of its population decline.

Surely this is the way to go rather than have the Chinese peg their currency to the devaluing dollar and ending up with a population that remains poor whilst the central Bank is stuffed full of worthless dollar denominated assets