“The trouble with our liberal friends is not that they’re ignorant”, Ronald Reagan once said, “it’s just that they know so much that isn’t so”. If we forgive the Gipper for his misuse of the ‘L’ word, we can see the truth in his remark. Nowhere do we see it more clearly than in the writings of Johann Hari, a man who doesn’t let his complete ignorance of economics prevent him from spouting off about it.

He was at it again last week when he called the idea that government borrowing of £450 million per day was anything to get worried about ‘The biggest lie in British politics’. He revealed an ignorance of history to match that of economics.

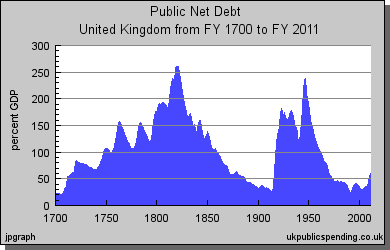

Take Hari’s claim that “As a proportion of GDP, Britain’s national debt has been higher than it is now for 200 of the past 250 years”. He challenges us to “Check it on any graph by any historian”. OK then.

Indeed, you see an awful lot of debt. But if you put in a few historical events you start to get a different picture. Context is everything, as they say.

Starting just before 1700 the British national debt does indeed rise at a fair rate. But consider that, in 1694, the Bank of England had been set up for the sole purpose of funding Britain’s frequent wars against France. So you see a steep rise in the debt to pay for the War of the Spanish Succession (1701 – 1714), the War of the Austrian Succession (1740 – 1748), the Seven Years War (1754 – 1763), the war in America (1775 – 1783) and then the various wars following the French revolution (1793 – 1815). And that’s just the major ones.

Indeed, 1815 and the battle of Waterloo stand out clear as day on the graph with national debt peaking at over 250% of GDP. After that, with the exception of the Crimean war (1853 – 1856) and possibly the Boer war (1899 – 1902), Britain didn’t fight a major war again until 1914. Resting on the twin Cobdenite pillars of peace and economic liberalism the British economy grew and the national debt collapsed.

The story in the twentieth century is similar. Debt rocketed when we went to war in 1914 and again in 1939.

So yes, in the narrow sense Hari is correct, our debt is low compared to 1815 or 1945 and many of the years after those dates. The difference, as some basic history shows, is that back then we had the defeat of tyrants like Louis XIV, Napoleon and Hitler to show for it, now we just have a bloated public sector and engorged welfare state.

This is where the claim made by Hari and others that our debt is not so bad historically is thoroughly disingenuous. There is a world of difference between running up debt to stop the country being conquered by Nazis and running up debt to insulate an already well funded public sector from the effects of a recession which has ravaged the private sector.

It’s not a difference supporters of vast government spending are able to see. Taking their cue from the Spender in Chief, Gordon Brown, they think that any money spent by the government is investment, which is a good thing. But ‘investment’ and ‘government spending’ are not interchangeable terms. Investment has a quite specific meaning; it is capital, usually money, put into an enterprise with the expectation of a return in the future. Thus, government building a road or improving education is investment. Government paying out for public sector workers to retire earlier than their private sector counterparts, for people to live in expensive houses in Kensington, for top rate tax payers to receive Child Benefit or teenagers to download music for their iPods is not investment. It produces no return. It is just spending.

Fortunately this crucial difference is understood better by the man and woman in the street than by many self proclaimed experts. This explains the recent finding of 57% support for at least the coalition’s measures.

We are not fighting a world war so there is no justification for wartime levels of debt and not all government spending is a good thing. This shifty argument is yet another desperate cry from people who still don’t want to give up their belief in visits from the Money Fairy.

Since when has a “knowledge” of economics been a necessary pre-requisite to spouting off. It never bothered John Keynes so why should it bother anyone else?

Not wanting in any way to support the ways of one Gordon Brown, debt is debt however you care to look at it and whether it is raised for purposes good or ill it has to be repaid out of income or out of asset sales, and creditors will look to see that the means of repayment are there before lending.

I think that this misses the real concern which is that of total debt within a country.

Much as aggregates are often misleading, the total debt burden felt by the people of the UK is better represented by both pulic and private sector debt. All this debt will need to be serviced by UK citizens’ activities. Indeed, given that the public sector has implicitly backed the banks, we might even assume them to be one and the same.

Bank debt within the UK is higher than its ever been in the past due to the fact that banks have created credit willy-nilly since the restraining hand of gold has been removed from them.

UK bank credit is currently greater than 100% of UK GDP, and this does not include outstanding derivatives contracts, corporate bonds etc.

Hence, the full debt number today is greater than 160% of GDP. Back in 1800 or so, private sector debt would likely have been negligable and so the comparison of 160% now compared with 200% then is a reasonable one. As noted above, 100% of GDP materially understates the endebtedness of the private sector, so the true number is likely higher.

In addition, the government is still running a deficit, and so increasing its debt burden each year (though the private sector is attempting to pay down its debt).

Added to the numbers above should also be included all the unfunded liabilities accrued by the government that are not captured in debt numbers (public sector pensions, capital elements of PFI projects etc.)

Finally – as if we needed any more problems – on top of this, the inflationary policies run by the bank of England ADD to additional debt every year. Our currency is effectively debt based, and so in order to maintain positive inflation numbers, the only way that this may be done is to add additional debt each year. It is for this reason that it is virtually impossible for the absolute debt burden to decrease.

It is correct that the total debt is more accurate yo measure the level of a country’s indebtedness. And according to McKinsey our total debt is 466% of gdp, a figure which concurs with the Taxpayer’s Alliance calculation of around £8trillion. This probably reflects not only our combined profligacy, but also our govt getting smarter about offloading its debt onto the private sector eg. PFI. We are in a giant debt trap.

He also keeps banging on about how the Roosevelt recession of 1937 was brought about by spending cuts and is therefore evidence of the superiority of Keynesianism.

I see your point waramess and yes, you are correct that ” debt is debt however you care to look at it and whether it is raised for purposes good or ill it has to be repaid out of income or out of asset sales”.

I would argue however, and have, that there is a big difference between borrowing which raises your capacity to pay it back and that which doesnt. For example, if I borrow money to go to uni I earn more with a degree. If I borrow money just to go to the pub, I dont.

Tim Lucas is right about two important things.

The big one is off-balance-sheet debt:

Governments have paid pensions in the past and have done so directly from taxation as they do currently. But, in the past that has always been in an environment where the number of working age people was much larger than the number of pensioners.

Official government debt numbers don’t state the true size of the debt. A private company would not be allowed to state it’s debt as the government does under normal accounting regulations.

I expect governments of the future will tackle this problem by reneging on implicit promises to certain groups. By finding taxes to claw-back some public sector pensions and/or by increasing the state-pension eligibility age.

Tim is also right to that the Bank of England must increase nominal debt year-on-year to maintain the inflation target of 2.5% in the long term.

That said I think Tim is wrong to worry about private sector debt. The same logic that applies to public debt doesn’t apply to private sector debt. Yes, some Britons are borrowing, that is mostly because other have lent. The balance is the quantity of external debt.

In a private debt contract one party buys a stream of future income by paying a sum to another. Both parties weigh up their situations in coming to that arrangement. In that process the business cycle certainly plays a part. But, largely the decisions are taken on the basis of each parties examination of their own financial position and how it’s likely to change in the future.

The reason government debt is of concern is because it’s involuntary. Taxes pay it off rather than repayments. There is no similar process of planning where a debtor works out the affordability of the debt. The debt’s cost is simply presented as taxation. The real risk then comes that as tax rates rise the Laffer curve means that revenue begins to decrease.

Hi Current

“That said I think Tim is wrong to worry about private sector debt. The same logic that applies to public debt doesn’t apply to private sector debt. Yes, some Britons are borrowing, that is mostly because other have lent. The balance is the quantity of external debt.”

Even if I were to accept your monetary equilibrium view of the world, I would still find fault with your objection.

The existence of the central bank acts to socialise risk such that private lenders are more eager to lend than they otherwise would be at low rates. Their judgements have been shown to be accurate time after time as the CB steps in to buy assets every time there is a small hint of a problem.

Hence, the quanitity of debt that can build up in the private sector is greater than it otherwise would be. Of course there is nothing wrong with debt per se, and all debt/credit nets out to zero. However, noting this is not particularly instructive. Of greater importance is the observation that if a large amount of private sector debt builds up relative to activity, then small economic fluctuations are likely to result in difficulties in repayment, increasing the chances of mass default and insolvency. These imbalances build up only as a result of central banking.

I’ll readily admit that private and public sector debt are indeed different – indeed ALL debt is different. However, given that it can get to unsustainable levels in both public and private sector as a result of state intervention, and that the state has frequently assumed private debt in the event of mas default, one reasonable indication of financial imbalance and instability it seem reasonable to consider both public and private debt together as a proxy for systemic financial risk.

For example:

Ireland had fiscal surpluses and was close to paying off its government debt prior to its banking crisis. This did not last long as the public sector assumed private debt obligations. Would you have pointed to the Irish economy being in rude health just prior to its crisis?

To some extent I agree… Central bank protections certainly give commercial banks a different incentives than would otherwise be the case. Deposit insurance and bailout protection gives a greater incentive to take risks. It may be true that “the quanitity of debt that can build up in the private sector is greater than it otherwise would be”. But, it’s by no means certain. We can’t really know the counterfactual, what would happen without central bank interference.

However, I think basic economics and historical evidence can show us several things about the subject. One of the most important is that in the long run the lending-borrowing market (which is sometimes called the savings-investment market) clears. If it does then increase in the quantity of funds for lending will lead to an increase in borrowing. Principally they will lead to an increase in borrowing for investment in business. Now, the central bank through creation of base money increase the apparent amount of savings. But, most of the funds for lending aren’t base, they’re from current account holdings, they’re real savings. ABCT doesn’t occur because central banks create a relatively small amount of unbacked fiat money. It occurs because this small increase triggers a much larger increase in fiduciary media. Then the injection effects and account falsification effects occur and we get an unsustainable boom.

That means that even without Central banks causing ABCT the funds available for investment would be almost as great as they are now. The difference is that if commercial banks had less government protection they would be invested with much more care than they do now. Rather than investing in risky ventures they would tend to invest in safer ventures with lower return.

It’s not that the levels of private debt we have had in the recent past and have now are “unsustainable”, rather the investments they are tied to are insufficiently secure. For that reason we shouldn’t really consider the quantity of debt to be the problem. The real problem is the quality of the usage of it. In a sense the same is true of government debt. If the government really were investing in our futures then it wouldn’t be a great problem.

I was living in Ireland at the time the government assumed the private sector bank debts, and I’ve lived there ever since. Ireland’s economy certainly wasn’t in “rude health” before that. But there have been plenty of times throughout history where countries have been heavily indebted and very successful. If you think about this it is perfectly natural. Where entrepreneurs are thriving they will borrow more to expand rather than simply relying on reinvesting profits.

Hello again Current,

“It’s not that the levels of private debt we have had in the recent past and have now are “unsustainable”, rather the investments they are tied to are insufficiently secure.”

I think that this is two sides of the same coin. Central banks existence allows lending not out of real savings, which results in more lending being done than ordinarily would be done at low rates. This – in turn – pushes up the value of the assets, and it is this over-valuation which makes lending against them insecure.

However, given that you partially agree with me but seem to think that the socialisation of risk by the central bank is a minor effect in resulting in a large debt build up, I challenge you to find me a counter example. If you’re able to find an example of private debt growing to a size similar to that of Ireland relative to activity, and yet was stable under a gold standard, I’ll moderate my view in-line with yours. If not, we’ll have to conclude that the logic I give you is reasonable but that we cannot know the size of the effects, and I will be likely to continue to think as I do as it has helped me in practice identify nations with unstable banking systems.

There is just one problem with debtphobes: they’ve been predicting that the allegedly excessive national debt will be the ruination of us for the last century, or more. But Armageddon never seems to arrive.

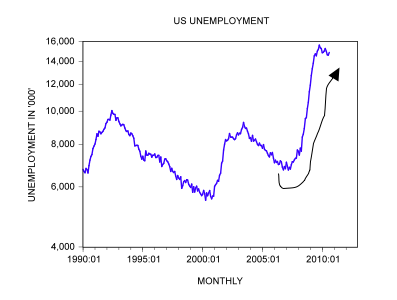

Of course there was the credit crunch. But that had nothing to do with the NATIONAL debt. It was caused by irresponsible loans to households.

For a list articles and quotes from doom mongers going back over the decades, see here:

http://rodgermmitchell.wordpress.com/2009/11/24/federal-debt-a-ticking-time-bomb/

Ralph,

To some extent you’re right. Though it’s relevant that many defaults have occurred in the past because of unsustainable debt levels. And by defaults I mean actual defaults and “pretended payment” in money made worthless by hyperinflation.

I don’t think that either type of default is an issue for the US or UK in the near future. Especially as pension payments can be reduced. The more important issues are:

* Most likely the expectations of pensioners will be dashed, the pension age will move up and state-sector workers will face some kind of clawback.

* The tax rises are needed to maintain interest payments while maintaining other spending. As those rise the disincentive to work rises.

But a debt rising at £5,000 per second is surely a problem?

nothing like the amount of debt has ever been seen on such a global scale before. And the debt monster really only became unshackled in 1971.In a mere 40 years we stand on the edge of the abyss.

@ Ralph Musgrave

Two points. It’s only in the last thirty years that money has been backed solely by politicians’ promises. So while there have been doom mongers about national debt for a long time it’s only since the 1970s that the effects on free floating currencies can be judged. This has been a period of exceptional peace between the great powers and enormous technological advancement, and also a period in which politicians in the West have debauched their currencies to fund their clients. The real ramifications of unsound money, strangling of small business and entrepreneurship through tax and regulation, soaraway entitlements and unprecedented life expectancies will not be seen for some time yet.

And servicing debt is a massive drag on the economic well being of a country, just as for a family. If you have a massive mortgage you may well continue to pay it, but it hugely restricts the other choices you have in life. We cannot choose, say, to seriously reduce taxes to encourage our economy because the debt still has to be serviced. You don’t have to go bankrupt to find that debt is destroying your life options.