Over the last few weeks there has been a growing realisation that the weaker members of the eurozone are caught in debt traps. When the “PIIGS” (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain) signed up to the eurozone they gave up the right to devalue, which is the traditional and delusionary escape route for sovereign debtors. But when you come up against the realities of hard money, this route is blocked. A temporary solution has been to gets banks to buy government bonds, but the banks can take no more. This leaves us with a banking problem, but fortunately their solvency is being underwritten by the European Central Bank, without which the eurozone would have ground to a financial halt.

The ECB, together with the national central banks, can only support these banks by writing a blank cheque on itself, while using all means possible to conceal and play down the losses in the system. This essentially is what happens with the good-bank/bad-bank solution: if the bad stuff is carted away to be dealt with out of the public gaze leaving the good stuff behind, what is there to worry about?

We have to keep our fingers crossed that the ECB continues to succeed in co-coordinating this vital task, and indeed, its strongest suit is that we all want it to succeed. But this still leaves us with the unanswered question of how to resolve the sovereign debt traps.

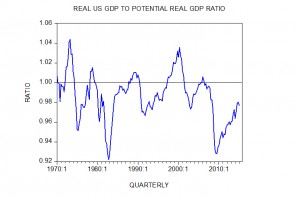

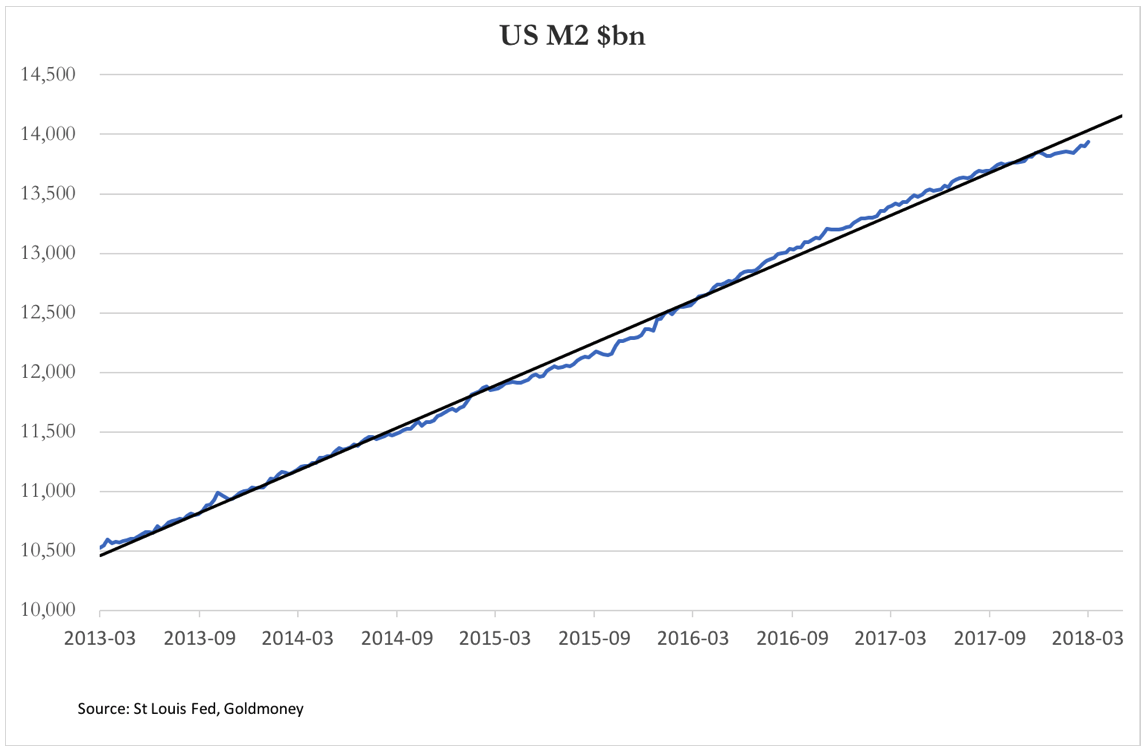

The problem is global. The eurozone’s debt problems, which also extend to France and Belgium, have only become obvious because of the inflexibility of the euro. But debt traps have also closed on the US and the UK, who can try to print their way out of trouble. Both these governments are fully committed to monetary inflation as the means to conceal and defer their own financial difficulties. This is what quantitative easing is actually about: it is the way a government funds itself when markets are unable or unwilling to come up with the money required. You bypass markets by printing it for your own banks to lend to you.

The idea that QE is primarily to help the economy recover is Keynesian guff, a cover for the true reason. Without it, the US and UK would have to compete for global savings at far higher interest rates. What price $2 trillion in new Treasuries with no QE? What price £175 billion in new gilts? The debt trap has already sprung. And few investors yet seem aware of the irony that loading up banks with Treasuries and gilts is exactly what the eurozone banks have already done for the PIIGS. Whatever the current difficulties faced by European banks and the US and UK governments and their banking systems, there is only one option for all of them: buy time by printing yet more money. This is why the banking system in the eurozone and elsewhere will survive. Banks need governments as much as governments need them. The cost of this survival will be borne by the unwitting saver, who has been frightened into cash only to find it being debased more rapidly than before.

This makes the recent fall in gold and silver prices nonsensical. But then just as the investment community walked blindly into stock market losses, they are just as clueless about the inflationary implications of rescuing sovereign debt.

This article was previously published at GoldMoney.com

A great problem of Belgium is that it’s got a Government again, which means a foolish élite with power to decide new spending.

The problem of France are not limited to the contagion spread from Greece and – maybe – Italy; the French economy is showing an increasing weakness, information is filtering from some non-banking multinationals which are reducing costs abroad to collect money to compensate the losses realised in France. Banks are simply the closest enteprises to Government level, so they are trying to direct fund towards themselves (see the fight on EFSF restructuring), but deeper problems are emerging (as an Austrian business-cycle theorist should expect).

Another QE round can postpone problems for further 2 years… thereafter the efficacy lag of monetary policy will make any further manoeuvre useless.

This article seems to be riddled with errors, such as:

“The idea that QE is primarily to help the economy recover is Keynesian guff, a cover for the true reason. Without it, the US and UK would have to compete for global savings at far higher interest rates.”

So why has the yield on 10 year bonds *decreased* since the end of QE in the US? And why did the same happen after the end of the last bout of QE in the UK?

Dan, it’s always problematic to try and assert reasons why in the context of financial markets. I would suggest that the reason Anglo-Saxon government bond yields have fallen is that the banks have been coerced into buying them. They get effectively free funding from the state and then invest (on a “risk free” basis to them) in government debt, and earn a guaranteed carry. Other investors, such as pension funds, also have little choice. Another possible reason is that institutional investors seeking safe havens have settled on Treasuries and Gilts regardless of the lack of value they offer, and there are questions of agency risk here (I doubt whether the managers would be buying for their p.a. portfolios). But also, QE1 ended, and was duly followed by QE2. No doubt we will see QE3 and QE4.. The bond markets are being utterly distorted by government and central bank manipulation, so there are no free market prices in operation here, in my view.

Tim, I agree that there are a number of reasons why gilt yields are so low. But the fact that yields have fallen since the end of QE in the US is strong evidence that the US would not have had to pay higher interest rates on its long term debt had QE not been carried out. Similarly with the UK. I am astonished that the author of this article is not aware of this, which completely invalidates his argument in my view.

enjoyed you article but the suggestion at the end that gold is a good buy leaves me uneasy