Eurozone leaders ordered their banks to raise additional capital last week to prepare for a partial Greek default. The continent’s banking industry didn’t yet receive a direct financial injection but will be allowed to appeal to national governments and the European bailout fund for assistance.

A recapitalization of Europe’s financial industry was championed by the International Monetary Fund and the United States as well as countries whose banks are excessively exposed to Greek debt, notably France. It is why President Nicolas Sarkozy liked to enable banks to tap into the European Financial Stability Facility that was set up last year to help countries, not companies, in financial distress so his fiscal challenges wouldn’t be aggravated. German Chancellor Angela Merkel insisted that banks raise capital from their own governments before raiding the bailout fund.

It’s a better plan, but one that will provide only temporary relief to Europe’s sovereign debt crises before making it worse.

Europe’s leaders agree that Greek debt levels have reached unsustainable heights. Its public debt is now worth 50 percent more than its entire economy and is projected to growth further in the coming years as Athens struggles to rein in spending substantially. Greek debt will be “restructured,” which means that roughly half won’t be paid back. European banks that have loaned to Greece could be in trouble. Even if they aren’t, other banks and investors might worry that they are, causing the market to tank. “Recapitalization” is designed to prevent that from happening.

In the short term, it could, but several weeks later markets would likely start wondering whether pumping billions of euros into a financial system that’s bloated with debt is really an intelligent strategy.

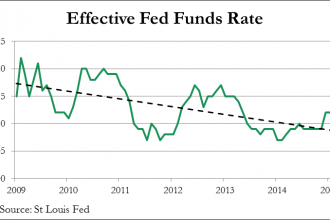

Western banks have been hesitant to loan money, to each other and to businesses, since the 2008 financial panic when the investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed. American and European central banks lowered interest rates in response, allowing banks to borrow cheaply in the absence of private sector confidence.

The European Central Bank has been more prudent than its American counterpart, the Federal Reserve, and didn’t buy sovereign bonds, from Italy and Spain, until this summer. The Fed, by contrast, has been financing American deficit spending by printing trillions of dollars for more than two years. Both have supported banks in the expectation that they would continue to extend business loans and mortgages.

They haven’t really—not enough to stir an economic recovery, anyway, because they realize that the market is still full of dislocations and excesses.

If there weren’t central banks or if they hadn’t intervened, those dislocations and excesses, build up in an era of “cheap money” when financial institutions knew that they were “too big to fail,” would have been cleared out in 2008 when Lehman collapsed and threatened to sink half of Wall Street with it. Prices that did not reflect real demand, especially in housing, where government policy had encouraged people without sufficient income to apply for mortgages, would have deflated—considerably.

Default and deflation however, along with potentially huge losses in personal savings, are politically unacceptable. So instead of failing, the institutions that created the crisis are now on life support while the housing market in many Western countries, and construction with it, is stuck. Homeowners aren’t willing to lower their expectations while buyers aren’t able to purchase at the prices they charge.

Recapitalizing banks after they bought worthless Greek bonds when they should have known better isn’t just wrong; it’s not going to work. If writeoffs are also expected for Portugal and maybe Italy and Spain, investors will realize that no matter how big the EFSF is made to be, the solvent countries in the north of Europe can’t afford to compensate them for their losses indefinitely. If the ECB also turns on the printing presses (which it doesn’t want to), that will be the clarion call for investors to get out. Interest rates on peripheral bonds will skyrocket.

The political willingness to reform structurally rather than cut several billions of euros in annual spending is virtually nil in Greece and Italy. These states are already bankrupt and waiting for Germany to pull the plug. It is king in the land of the blind (or broke actually) but doesn’t have the cash on hand to bail out half of Europe. Some countries just won’t change until they’ve hit bottom. The sooner the better, for the longer banks have to wait for the inevitable, the longer they’ll avoid investing in enterprises and loaning to other banks — they don’t know which will survive the reckoning and which won’t. Recapitalization would thus make the problem worse by providing a false sense of security that cannot last.

This article is based on one previously published at Atlantic Sentinel

Comments are closed.