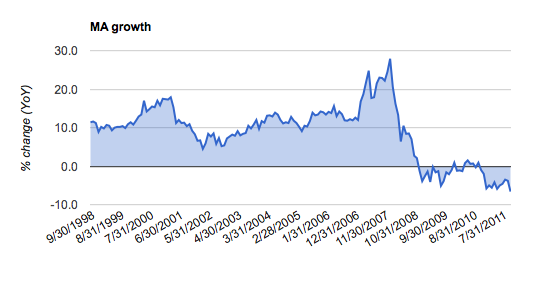

Regular readers will know that The Cobden Centre’s sister roundtable – Kaleidic Economics – is engaged in measuring the MA measure of the money supply, as discussed here several times. In October 2011 MA fell by 6.6% compared to the previous year, which is around twice the recent rate of contraction. As turmoil regarding the Eurozone and threats of a double dip recession continue, good policymaking requires good data. And the monetary aggregates paint a gloomy picture.

Then why is inflation (albeit government-defined) still around 5%?

Afternoon Richard,

There is always a time lag between the monetary disturbance and it showing up in prices. This can be up to three years and there is a lot to still feed its way through the system.

Also, when we see the rate of growth slowing , despite the massive amounts of liquidity placed into the system, the deflation would be much more pronounced.

The economy is in a truly shocking state indeed.

I think that the following is correct, following the Rothbardian principle of looking at where the new money injected:

During the great increase in leverage, the source of new money was in the form of credit extended by the commercial banks. Hence, the place where that money tended to be applied first was into investments. Thus property, equities, financial assets against which commericial banks tended to lend massively appreciated in value. While some of this money went into consumption (through equity withdrawal schemes, hedge fund managers’ bonuses etc.), most of the money stayed tied up in assets. Thus, there was not much pressure on the price of goods upwards. While monetary inflation numbers were high, this did not therefore show up in RPI.

As the commercial banks deleverage, the money supply contracts. In order to attempt to arrest it, the central bank prints money. Thus, the mechanism of money creation has changed, with commercial loans being replaced by an expansion in the central bank balance sheet. The central bank is principally a buyer of government bonds, not private real estate or other financial assets. Thus, the government is increasingly subsidised at the expense of the rest of society. Since the the government tends to spend on payments to people, this money is more likely to show up in consumption, which would show up in RPI.

Hence, one ought to expect RPI to grow in excess of money supply. We can expect financial assets to go up by less than the cost of living for a good time to come yet.

Of course there are other effects to consider: productivity growth and international exchange rates also affect RPI numbers, and of course the statistics themselves are bogus. However, I think it likely that the affect I descrive above is important.

Just to add on to Tim’s point, currently banks are cutting back on lending and looking to get repaid on existing debt where possible occasionally by liquidating (or forcing borrowers to liquidate)projects. They are also attempting to raise their capital ratios (this reduces the amount of money in the economy) to reduce the riskiness of their balance sheets.

This process of liquidating outstanding and unprofitable positions is being frustrated by the BoE’s poorly thought-out easy money (low interest rate) tactic. This is because it is impossible to exit from long term hedges, based on previously higher interest rates when the BoE maintains ridiculously low interest rates.

“This is because it is impossible to exit from long term hedges, based on previously higher interest rates when the BoE maintains ridiculously low interest rates”.

Hi Robert – I don’t understand this. Would you mind clarifying further? Which hedges are you referring to?

Shouldn’t it be easier for the banks to exit positions while there is more money than their would be in the absence of central bank action? For example, UK property values, government bond prices are kept high by the easy money policy. Banks are the largest holder of mortgage assets and government bonds. Hence, with policy as it is, this allowing the banks higher values than would otherwise be the case to liquidate and shrink their balance sheets.

If banks are not liquidating, it is likely because they are marking their assets to model, rather than to market. The act of selling any of these assets would crystalise a loss relative to their books and reveal them as insolvent. Considering the 20x leverage of the majority of the Eurozone banks, if they were to mark their assets to market today, I presume that a high proportion would be insolvent. Hence they are only kept alive by a constant flow of newly-printed central bank money.

Hi Tim,

I refer specifically to my industry, commercial real estate lending. By hedges I mean interest rate swaps. Prior to 2007, banks in my industry were lending for about 5 years but the maturity on the swaps would match the leases which could go out for 10 to 20 years. The idea was that this would protect the Borrower and by extension the bank from drastic increases in interest rates.

Unfortunately, no one expected the BoE to reduce interest rates to near zero. The result is a MTM on the swap that coupled the underlying loan, results in LTVs far beyond 100%+ that make it impossible for banks to exit many of their loans without taking substantial losses… which today they cannot afford.

I think insolvent banks should be allowed to fail. Effectively stealing money from the general population to keep inefficient businesses in operation is unethical in too many ways to count.

But my opinion aside, what the BoE has done is a one size fits all solution that does not suit banks in my industry. In general, they are retarding the necessary process of malinvestment liquidation. Losses must and will be taken. All the BoE can do is make this process last longer.

Last point. Would you buy a bond that you knew only held its value because of QE? Personally I would sell it short…

Inflation is properly defined as an increase in the supply of money in excess of the increase in the supply of goods and services in the economy as a whole, the result of which is a general rise in the level of prices, all other things being equal. Deflation is the opposite.

So, first, we need not only to look at the change in the supply of money. But, also at the change in the supply of goods and services. If they both change at the same rate, all other things being equal, there is no reason to believe that the general price level will change.

Second, It takes time for a rise or fall in the supply of money to affect the general price level.

Third, the supply of money is only one side of the equation. Changes in the demand for money also need to be considered.

Fourth, it is very hard to measure the general price level in short time frames in minute intervals, even though that is what governments pretend to do.

There is a debt collapse threatening in Europe. This is highly deflationary. If the central bankers of the world don’t print money to bail out the sovereigns and the banks, the general price level will certainly fall, a lot. The price of everything will fall, including the price of gold and silver.

However, the more likely scenario is, that, in the mid term, say, the three year time frame, the printing presses will be fired up and will be running full steam around the clock. In that case, we will see incredible rates of rising prices.

Sorry for the ignorant question.

But what would the ‘comparable’ money supply measure be to MA?

Another thought.

What has happened(percent changes) with those traditional money metrics?

Thanks.

@joebhed

MA is pretty similar to M1 or MZM but I’m not aware of decent estimates of them for the UK.

We compare MA to the two traditional monetary aggregates for the UK (Notes and Coin and M4) here:

http://www.kaleidic.org/data/#KA01

It is probably more useful to look at M4x rather than M4, but since we go back to 1997 we wanted something comparable.

“Inflation is properly defined as an increase in the supply of money in excess of the increase in the supply of goods and services in the economy as a whole, the result of which is a general rise in the level of prices, all other things being equal. Deflation is the opposite.”

I disagree. Inflation is an increase in the money supply, period [or full stop if you prefer]. I do agree that deflation is the opposite.

Craig, I don’t support fiat money. But, even if gold was money, the supply of it would increase over time. So long as that rate of increase in the supply of gold would be in line with the general rate of increase in the supply of goods in general nothing harmful would occur. And, in fact, this situation would be normal, healthy and expected. Why then would we ascribe to it a negative connotation such as ‘inflation’?

Gold is a good like any other. An increase in gold relative to other goods would be beneficial as it means that gold and gold products would be cheaper. This not the same as increasing fiat currency or fractional reserve bank notes at all.

Further, who determines this general rate of increase in the supply of goods? You might say the market. I say there is no benefit to increasing paper money either in line or out of line with the so-called general increase in the supply of goods.

If the amount of gold money stays the same and the supply of goods increases, then their prices relative to gold decreases. This is nothing more than a beneficial increase in productivity and general increase in wealth.

“An increase in gold relative to other goods would be beneficial as it means that gold and gold products would be cheaper”

This is an ongoing point of disagreement.

The monetary value of gold far exceeds its value for use in industry and jewellery. And its monetary value is a function of its scarcity.

Suppose the world finally returned to a gold standard, and a few months later a storm of gold meteorites increased the gold supply tenfold.

Would we rejoice? Or would we resent the disruption to prices and contracts, and the sudden unfair redistribution of wealth?