Back in December 2011, Anthony J. Evans’s blog post on this site and City AM article on government investment activity displacing private investment offered timely insight into the crowding out effects that can arise from government spending. The use of aggregate investment data in the article also highlighted the problematic issues associated with the identification of causes of decline in private investment and understanding the relevant policy prescription for improving this (which Evans correctly identifies as “hands off”).

Aggregates mask pertinent issues and prevent legitimate questions from being asked. How do we know that any growth in private sector investment has not been artificially stimulated by other levers, such as money and credit injections? Furthermore, where this money enters into the private sector influences the future shape of its capital structure and therefore where the forthcoming correction in activity is most likely to take place, once the stimulus has worked its way through the economic system. Therefore, what can we tell from aggregated data about how far through the business cycle the private sector is and what the true impact of capital displacement has been on its capability to begin investing again?

Tensions in the approach to capital…

Austrians dislike the standard approach neoclassical theory takes towards capital. Viewing capital as a homogenous glob leads to the over-aggregation of capital structures on a number of scales – from economies and industries, even down to individual firms. Of course, treating capital in this way allows its use as inputs into mathematical models, i.e. manipulation of data through the likes of both cost and production functions.

Yet, taking this approach means the prevailing analytical paradigm overlooks and therefore misses out on a rich tapestry of information and insight which is available at disaggregated levels. The Nobel Prize winner Finn Kydland highlighted this aggregation process succinctly in his Prize lecture (2004). Back then he disclosed how he crunched data on literally millions of consumers and thousands of firms to arrive at the technical coefficients that fed into what were the forerunner real business cycle models for the current crop of state of the art macroeconomic models.

It could be said that the one advantage that the neoclassical paradigm has is that it is reasonably consistent in its treatment of capital, whereas capital is still a relatively contentious area for Austrians. Any supposed advantage in this regard is easily outweighed by the depth of analysis offered by the Austrian approach, which views capital as heterogeneous and heavily influenced by time.

I am still coming to terms with the Austrian literature on capital theory but to me the capital debate turns upon the degree of subjectivity employed in the analysis of capital. For instance, Lewin (1999) highlighted how this range of views manifests itself from a more quantitative Bohm-Bawerkian (neo-Ricardian) approach based upon the average period of production, through to the completely subjectivist views held by the likes of Lachmann[1].

It is not the goal of this article to explore in depth what can be detailed and somewhat abstract debate around capital theory. Instead, I want to concentrate on one aspect of Lewin’s analysis, and use this to illustrate how theory can be combined with available statistics to shed some light on changes to capital composition over the course of the business cycle.

… provide the genesis of an idea

The latter stage of Lewin’s book pushes the idea of subjectivity out to an interesting limit – that of what he terms the “Capital Based View” of the firm (or CBV). This is further elaborated by Lewin and Baetjer (2011) in an article for the Review of Austrian Economics[2]. The CBV approach to analysing the firm argues that entrepreneurs organise firms as sets of physical and human capital. Such ordered combinations of capital carry embodied knowledge, not only with regard to their own use, but also entrepreneurs’ knowledge for using this combination of capital to satisfy demand in the market.

The firm’s customer-satisfying capital combinations, whether meeting final consumers’ demand or producers’ intermediate demand, generate value over time and therefore derive their own values in turn. If this view is correct, that firms are portfolios of capital organised by entrepreneurs, then looking at the spread of firms across the economy should tell us something about the distribution of capital. This is not to be confused with providing an absolute value of capital, as in the neoclassical sense, because the heterogeneous nature of capital goods and entrepreneurs’ subjective valuations of these goods rules this out.

Why would knowing something about the potential distribution of capital in the economy be useful?

Because by looking at the composition of firms across industries and time tells us something about how entrepreneurs are allocating capital in the economy, particularly how these allocation decisions cross the different phases of the business cycle.

Case study using New Zealand business data

The recent business cycle in New Zealand propagated itself through the real estate sector. The cycle started in earnest in the early 2000s following a period marginal economic growth due to the after effects of the Asian financial crisis (late 90s) and the bursting dotcom bubble. It reached a crescendo in 2008 and began to unravel following the onset of the global financial crisis, but realistically prior to 2008 there were signs of trouble in the economy.

Easy monetary policy kicked things off, which helped to stoke demand in the market for existing houses (consumer demand). This was also assisted by real effects through some positive migration after the 9/11 terrorist attacks and local council regulations limiting development (restricting supply). Eventually the activity in the consumer end of the market (both speculative buying and normal demand) triggered investment in the development end of the market (i.e. goods further away in time from production), with more money also beginning to flow into commercial real estate.

At the same time, the country also experienced a consumption-driven boom on the back of increases in equity – wait for it – now inherent in the increased values of property, and from increased employment as more of the easy credit washed further and further through the economy.

This has all blown up in a rather nasty way with many of the speculative property developers going bust, along with some reasonably high profile leveraged purchasers of commercial property, which has had a flow-on impact on the non-bank finance company sector. While the formal banking sector has managed to maintain its ongoing liquidity and viability, many of the finance companies have gone to the wall, taking around NZD 6 billion with them in local depositors’ savings. There are prosecutions going through the court system at the moment of ex-finance company directors over the issuance of misleading prospectus declarations.

So what impact has this had on the structure of production in the New Zealand economy?

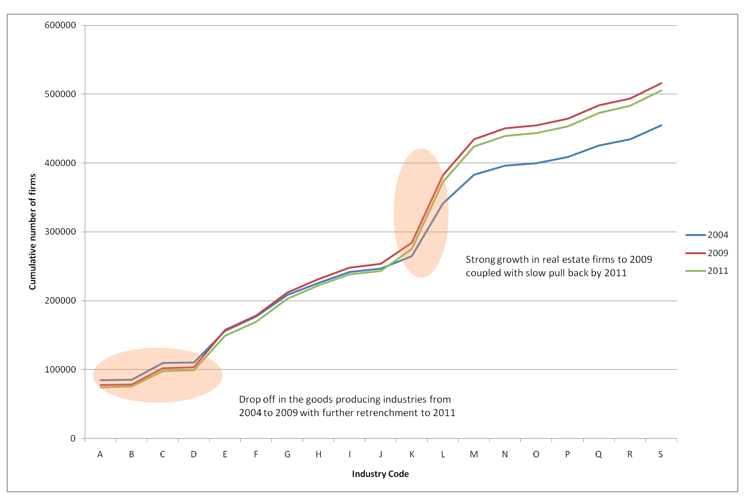

Assuming that firms are reflective of the capital holding choices of entrepreneurs, then the changes in the structure of production brought about by the boom-bust cycle are mapped in Figure 1. These figures are taken from Statistics New Zealand’s business demography database. The series runs back to 2000 on an annual basis and is a snapshot of the number of firms engaged in economically significant activity (i.e. to be included, firms have to cross a minimum threshold of activity).

The horizontal axis in Figure 1 represents industries where firms are located based upon the Australia-New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC); a list of firm definitions by industry code is included at the back of this article. The data is represented as the cumulative number of firms in the economy moving left to right across industries, from the primary sectors beginning at A, through to manufacturing at C, with the service sectors beginning at F. Note the data could have been organised along the lines of the Hayekian triangle, however this would have required more research and gone beyond the scope of what I want to communicate here.

Each line of the graph shows three time periods – 2004, 2009 and 2011, with the 2009 data illustrative of the peak in the cycle because the survey that underpins the statistics is undertaken every February. The starting point of 2004 was chosen partly because it represents a period when the boom was well and truly underway and also because for that year going forward the statistics agency changed the way it recorded the presence of real estate firms by lowering the capture threshold. Lowering the threshold had the effect of increasing the number of real estate firms reported on from there on, but not back calculated to the start of the series.

So, Figure 1 shows what has happened to the composition of firms in the economy over the build up in the boom period followed by the climax of the boom and the ensuing bust. The shifting of the lines over time shows the change in the structure of production as entrepreneurs alter their investment patterns. Between 2004 and 2009 it shows the real estate sector expanding while the goods producing industries suffered a contraction in the number of firms.

This is illustrated with the shaded circle towards the bottom left hand corner of the graph indicates the contraction in the goods producing industries, while the shaded circle in the middle of the graph shows the expansion of the number of firms in the real estate and associated services sectors. For example, there was a significant pick-up in the financial services sectors (K) and professional services (M) in line with the real estate boom.

By 2011 the decline in the goods producing industries had continued, while the financial and professional services sectors were also in contraction. This was not matched by a similar fall in the real estate sector relative to the others, demonstrating the hang-over effects in the economy of misallocated capital and the attempts by the Reserve Bank to stave off or lessen the effects of the necessary correction through easy monetary policy.

The impact of these changes has been to re-weight the economy towards particular sectors of the service industry, namely non-tradeable sectors around the property industry. Reserve Bank figures (here) for historical sectoral claims show the pattern of increasing funding flowing towards real estate and households relative to other sectors of the economy. During the boom period the push within the non-tradable sectors through property related activity helped to depress the traded goods sector through increased costs at home (e.g. the bidding up of wages and the price of other resources).

Increased consumption of imports and capital inflows were in part the cause of the exchange rate appreciating which helped to make exporting and import competing firms less competitive. With this combination of forces acting on the economy it is easy to see why entrepreneurs and investors moved away from the more “risky” activities associated with goods production and moved toward the relative “safety” of the “sure thing” property market. The swing in this direction was associated with a range and scale of activities, from mum and dad investors using tax favourable loss attributing qualifying companies[3] (LAQCs) to invest in residential rental properties, through to sophisticated property development and owning companies which separated assets out into different entities[4].

Conclusion

Taking the approach developed in this article highlights the beauty inherent in Austrian theory, in terms of being able to take concepts right down at the micro level of analysis, such as the capital based view of the firm, and extend them through to analytical insights at the macro level of analysis – which is what I have hopefully demonstrated here. However, because of the heterogeneity of capital no one measure is ever likely to be able to reflect the true dynamics of capital in an economy.

It is more probable that a range of indicators will provide a temperature check on the state of capital allocation in the market, especially since aggregate measures cannot account for the relative changes that underscore true macroeconomic dynamics. In this regard looking at the composition and distribution of firms across the economy provides insight into how entrepreneurs are likely to be holding portfolios of capital at different time points through the business cycle.

Recently released official employment measures in New Zealand indicate that while unemployment fell, employment growth was slow and labour force participation declined slightly. The statistics indicated that full-time employment declined, so the small increase in employment came from part-time positions. Given what we have discussed above with regard to the displacement of firms in the goods producing industries, is it any wonder that employment uptake in the so-called recovery phase is slow and restricted to part time positions (probably in lower value service industries)? What sort of structural unemployment does this create amongst the younger generations and those semi-skilled and skilled workers? In the light shed on firm distribution it is easy to see why recovery is haphazard and there is discontent amongst the masses.

Since Evans’s article, both Detlev Schlichter with this commentary on the 4th of February and Toby Baxendale with this post on the 12th of February have weighed in on the misleading picture that can be obtained with an obsessive focus on aggregate data. It is time to look beyond aggregates towards a richer picture of economic activity.

Appendix – ANZSIC industry classifications

- A. Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing

- B. Mining

- C. Manufacturing

- D. Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste Services

- E. Construction

- F. Wholesale Trade

- G. Retail Trade

- H. Accommodation and Food Services

- I. Transport, Postal and Warehousing

- J. Information Media and Telecommunications

- K. Financial and Insurance Services

- L. Rental, Hiring and Real Estate Services

- M. Professional, Scientific and Technical Services

- N. Administrative and Support Services

- O. Public Administration and Safety

- P. Education and Training

- Q. Health Care and Social Assistance

- R. Arts and Recreation Services

- S. Other Services

[1] Lewin, Peter (1999). “Capital in Disequilibrium: the role of capital in a changing world”. New York, Routledge.

[2] Lewin, Peter and Howard Baetjer (2011). “The Capital-Based View of the Firm”; Review of Austrian Economics, published online 9th April 2011, Springer.

[3] Note changes to New Zealand tax law in 2010/2011 removed many of these advantages and I believe LAQCs no longer exist in this form.

[4] Note this form of asset spreading for risk management purposes has ended up not working out so well for these property owners and developers, as the extent of the systemic issues within the economy meant multiple companies have been dragged into receiverships and liquidation at once. Contagion was (and still is) alive and well in the speculative property world.