Two weeks ago in the Budget debate, I set out how “monetary activism”, which is one of the pillars of the Government’s strategy, could go wrong:

Steve Baker (Wycombe) (Con): I refer the House to my interest in Cobden Partners.

This is a Budget of fiscal conservatism and monetary activism. It is a Budget, above all, of economic expectations, setting out to people that we will reward work, support families, help those looking for work, back business and back aspiration. In the short time available to me, I would like to speak directly to the point of monetary activism, which is one of the Budget’s key pillars. I hope the Government will not take it as a criticism, because the Chancellor has emphasised that the Bank of England is independent and, of course, its policies are symptomatic of those followed all around the world.

Over the past 13 years under new Labour, the money supply expanded from about £700 billion in 1997 to £2.2 trillion in 2010. That was through a massive expansion of bank balance sheets—a huge amount of monetary activism led by central banks, with the Bank of England keeping interest rates too low for too long. That goes to the heart of points that Opposition Members have made. It has redistributed wealth towards the south-east and the first recipients of new money. I would say that it is at the heart of our difficulties. The scatter chart in the Red Book shows how the balance between our fiscal position and the bank balance sheet position is interlinked, and has placed us as an outlier.

When many people look at monetary activism, and quantitative easing in particular, they get worried about inflation—and why not? It would, however, be hysterical to worry about hyperinflation at this stage, when the asset purchase facility is at £325 billion—just one seventh of the money supply. I would nevertheless like to sketch out something that troubles me in my darker moments.

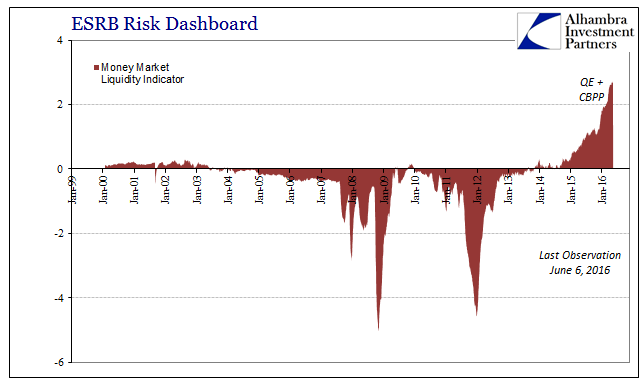

Right now, there is not a problem, but a housing bubble became a banking crisis—at least not a problem of inflation—which became a sovereign debt crisis, which has now been turned into an asset bubble in the bond market. The Bank of England has deliberately inflated bond prices in order to suppress long-term interest rates—interest rates that our constituents cannot do without because they are so indebted. The problem is that, as we know, all bubbles burst; the questions are when and what might burst the bond bubble. Inflation expectations might do it. If we were to look at M4 and M4ex from the Bank of England, there is no reason to doubt its inflation forecast. If we look at my preferred measure of the money supply, however, which is Kaleidic Economics MA, we can see that from July last year, year on year money supply growth was minus 2%; today, money supply is growing by that measure at plus 6%. We should thus be very cautious indeed about the Bank’s forecasts.

If the bond market bubble bursts, there will be pressure on the Bank of England to continue to prop it up. That will lead to further quantitative easing and create an expectation of rising interest rates. That could cause a flight from the bond market into cash; and it could cause the public, as they see QE continuing, to lose faith in cash itself, which could lead them to start spending.

Karl McCartney (Lincoln) (Con): Will my hon. Friend give us an idea of when he thinks this bubble might burst—in the near or the distant future?

Steve Baker: I am grateful to my hon. Friend, as this is a critical problem. It is a problem of expectations; it about the human mind, which is extremely difficult to predict.

I was saying that, as we go through, we could find that people lose faith in cash. If they do that, they will spend it, and move into real value. Keynesians could end up celebrating an apparent boom, but actually one that is a crack-up of the currency. I sketch these events not to frighten, but to set out a perspective for the House of which we should be aware when we know that the central banks and the Bank of England have deliberately inflated this bond market bubble.

We could end up facing a choice: if prices and wages are accelerating, but less quickly than the money supply, the Bank of England will have to choose whether to supply more money or whether to abandon that monetary inflation and reveal the underlying havoc created by decades of inflationary money. Perhaps new money, instead of real resources, can be used to paper over the cracks. Perhaps expectations can be managed to avoid the bubble bursting. If I were to quote with just a little adaptation something that Hayek wrote in 1932, I would say: “We must not forget that for the last 86 or 88 years, monetary policy all over the world has followed the advice of the monetary activists. It is high time that their influence, which has already done harm enough, should be overthrown.”

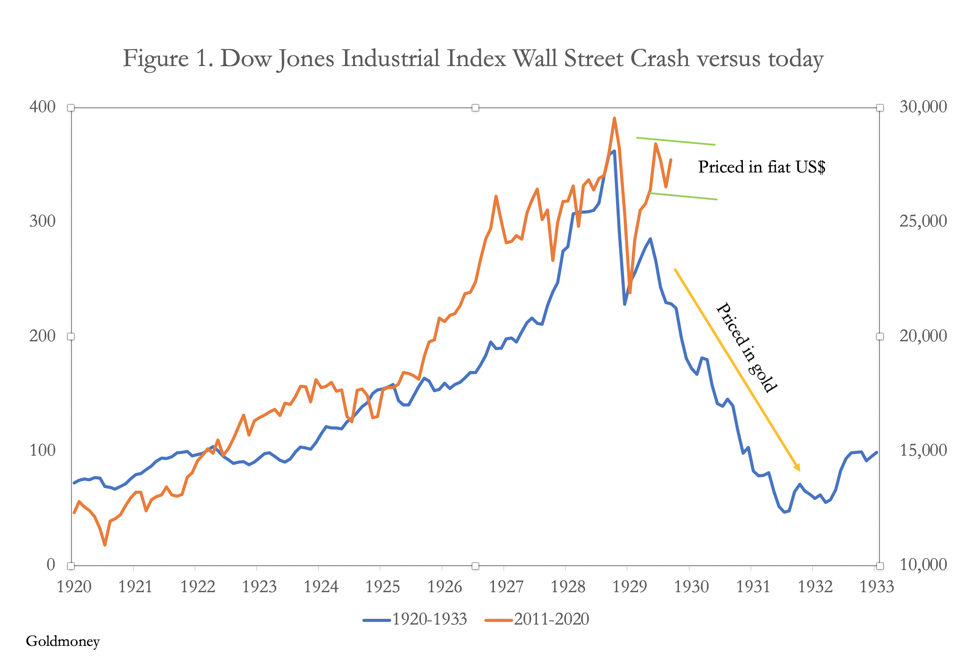

The quote at the end is derived from the 1932 Preface to Hayek’s Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle, which is available in this collection (PDF). The truth is that little really new is happening in the world. The same bad ideas about monetary stabilisation which turned a correction into the Great Depression are still at the core of mainstream economics, thanks to the persuasive intellectual errors of Keynes and others. In 1932, Hayek wrote:

Far from following a deflationary policy, central banks, particularly in the United States, have been making earlier and more far-reaching efforts than have ever been undertaken before to combat the depression by a policy of credit expansion—with the result that the depression has lasted longer and has become more severe than any preceding one.

The five-page Preface is well worth a read for an insight into how little is really new in the world. It’s true that finance and financial theory are more sophisticated now, but the fundamental laws of cooperation in society are unchanging. What changes, is how we understand them and how, Canute-like, we try to escape the consequences of our actions with ever greater interventions by authority. It’s not a healthy trajectory.

Thankfully, these ideas are becoming increasingly mainstream. Just after I spoke, the BBC Radio 4 programme Analysis transmitted What is money? featuring my colleague Gordon Kerr. Given Detlev Schlichter‘s recent appearance on Start the Week and a range of other Cobden Centre media successes, I am increasingly optimistic that we may shift the terrain of the debate on the financial crisis and, eventually, deliver reforms capable of supporting sustainable prosperity.

Related reading:

- Hayek, Prices and Production and Other Works (Kindle, PDF)

- Mises, The Causes of the Economic Crisis: And Other Essays Before and After the Great Depression (Kindle, PDF)

- Rothbard, The Mystery of Banking (hardcover, Kindle, PDF), especially pp66-74, which sets out how inflationary expectations can lead to hyperinflation.

- Schlichter, Paper Money Collapse: The Folly of Elastic Money and the Coming Monetary Breakdown (hardcover, Kindle)

- And the Cobden Centre Primer

This article was previously published at stevebaker.info

It is a pity we don’t have any member of parliament such as Steven Baker in France.