For some months now, leading indicators the world over have been pointing toward slower growth ahead. It’s not just about the euro-area any more. China, India, Brazil, the US, Japan—most economies appear to be slowing. A major recession may not be on the way but below-trend growth has already arrived and looks set to continue into 2013. Business cycles being a fact of economic life, the current slowdown is not surprising in of itself. No, what is surprising is the upturn that preceded it. By various measures, it was deeply disappointing.

First, in the developed economies, the level of real GDP has yet to materially exceed the previous peak reached in 2007. For a downturn to begin without having exceeded a previous output peak is one way to distinguish a ‘depression’ from a ‘recession’, a semantic point discussed in a previous Amphora Report, ‘From Deflation Push to Inflation Shove‘ (June 2012).

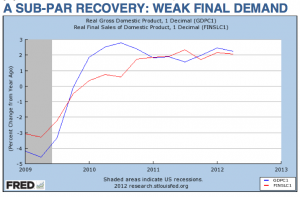

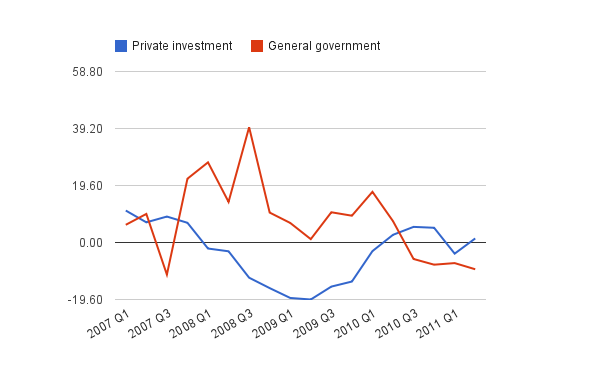

Second, while headline growth has been disappointing, the mix of growth has also been poor, that is, it has been driven somewhat less by real fixed investment and final demand, and rather more by stimulus-fueled inventory accumulation. Indeed, in the US, real final demand, considered to be the ‘core’ rate of GDP growth, has struggled to rise above 2% y/y, far below the level seen in past recoveries.

Now inventory accumulation is not necessarily a problem. There is nothing wrong in principle with producing today that which will be consumed next year. But businesses must remain confident that the inventory will indeed be consumed at some point and won’t cost too much to finance in the interim. Lose that confidence and businesses will seek to reduce inventory, with all the negative implications for jobs, incomes and growth generally.

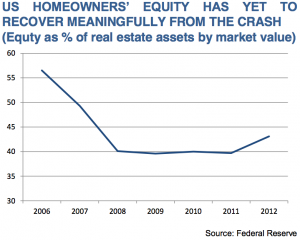

Now why might businesses be concerned that inventories are too high? Well, in the US, the inventory to sales ratio has been creeping higher, albeit from a low level. More worrying, personal disposable income growth is weak, in part due to the large decline in the workforce participation rate over the past three years [1]. And, notwithstanding a small rise in the household savings rate since 2009, households have yet to meaningfully de-leverage. Indeed, the truth is rather the opposite, as household net worth has plummeted as a result of the housing market crash. There is thus little if any so-called ‘pent-up demand’ to absorb accumulating inventory.

Corporations may look in comparably better shape. Profit margins are elevated. They have accumulated much cash on their balance sheets in recent years. But as I have pointed out before, they remain unusually highly leveraged in a historical comparison [2]. The aggregate corporate debt/net worth ratio, at nearly 70%, is much higher than is normally associated with high rates of fixed investment. No, corporate investment is not going to lead the way out from here. As is the case with households, there needs to be an economic de-leveraging first. This is a simple, unavoidable economic fact, policymaker rhetoric to the contrary notwithstanding.

The trick thus becomes how to engineer this de-leveraging. Central banks are resisting a natural, deflationary de-leveraging in which prices decline to levels that clear the excess inventory and excess capacity in various sectors of the economy. (By ‘excess’, I mean that which has run ahead of underlying real income growth and net savings.) This resistance follows directly from their stated aim of rescuing their weak financial systems, still drowning in distressed, illiquid assets.

Preferable from their point of view is to engineer an artificial, policy-driven reflation instead, as this will erode the real debt burden and keep the financial system more or less intact as is. Eventually, so the thinking goes, through inflation, incomes will rise to levels that can service the accumulated debt such that healthy, sustainable growth can resume.

Perhaps central bankers can pull this off, although putting fresh capital in the hands of those who misallocated it in the past doesn’t exactly come across as a compelling long-term growth strategy. It is as if a failing corporation (USA Inc), rather than firing underperforming managers (Wall St), gave them large bonuses instead (TARP). Who in their right mind would invest in such a firm? When it becomes a national policy, who in their right mind would invest in such a country?

In any case, what policymakers won’t tell you is that this sort of artificial reflation is a wealth transfer from the real, productive economy to distressed, in some cases politically-connected firms that receive first access to the new money entering the economy. This is important. While a printing press can’t create wealth, over time it can transfer it from those who don’t have access to the press, to those who do. Indeed, if printing presses actually created wealth and distributed this evenly and fairly throughout society, why on earth would counterfeiting be illegal? [3]

FROM QE TO CURRENCY AND TRADE WARS

Regardless of the insidious wealth transfer it engenders, artificial reflation can be difficult to engineer when faced with such a huge accumulated debt, as so-called ‘balance sheet effects’ — debt write-downs — can overwhelm ‘income effects’ – the rising nominal incomes associated with inflation. There is, however, one method that trumps all others: currency devaluation [4]. Yes, this may clearly and directly rob savers (and importers) to bail-out borrowers (and exporters), but if other methods fail, then devaluation will ensure a de-leveraging of the economy. It will also make it poorer overall, but the borrowers, being bailed-out in the process, avoid bankruptcy and thus are naturally all for it. Who cares if the pie shrinks a bit if your slice increases disproportionately in size? Such is the attitude of an established, self-serving elite.

By announcing QE3 last month, the US Fed is raising the stakes in the reflation game. Asset purchases are now ‘open-ended’; in other words, the Fed will buy up whatever is required to generate what it believes is a sufficiently high rate of inflation. If that sounds radical, it is. This is the greatest economic central-planning experiment of modern times, one that threatens to wreck the US economy via chronic resource misallocation as described above.

Whether or not QE3 results in a material decline in the value of the dollar relative to other currencies is unclear. There are two sides to any exchange rate, and many other economies have issues of their own, including their own versions of QE. Who succeeds in devaluing against whom is one of the great unknowns at present. But be under no illusions: A ‘currency war’ of sorts is already underway. (Brazilian Finance Minister Guido Mantega seems particularly fond of this term, having used it on multiple occasions to criticise US monetary policy. He has also claimed that the current currency war is leading toward a more general global trade war.)

Back in October 2010, in the Amphora Report titled ‘Begun, The Currency Wars Have‘, I considered the potential implications of a general global currency war:

Currency wars might appear to be zero-sum. But this is true only up to a point. For if all countries intervene to weaken their currencies in equal measure, no country succeeds in devaluing versus the others. As such, they might then resort to raising trade barriers or enacting currency controls which restrict the flow of capital across borders. These sorts of actions cause substantial economic damage however and are thus hugely counterproductive. The 1930s were characterised by, among other things, currency devaluation, capital controls and rising trade barriers such as the infamous “Smoot-Hawley” tariff.

While potentially growth negative for the global economy, currency and trade wars can, however, contribute to rising price inflation. Why? Well, the weapons of currency wars are the printing presses. The more you print, the more you can weaken your currency, or at a minimum prevent it from rising. He who prints most, devalues most and “wins”. But if all print in equal measure, exchange rates don’t move, but the global money supply soars. As such, currency wars don’t stimulate real economic growth – indeed they are much more likely to weaken it – they stimulate only nominal growth, that is, inflation. The net result is most likely to be a global “stagflation”. [5]

Now imagine that the current global downturn is met with even more aggressive attempts by various countries to weaken their currencies, increasing uncertainty with respect to currency and trade policies. Tariffs and import quotas for sensitive goods begin to rise from historically low levels. Globalisation, as it were, begins to go into reverse.

While the neo-luddite, anti-globalisation crowd might rejoice at this development, for investors, there will be little to celebrate. Modern corporations are highly leveraged to relatively free trade. They are already facing higher input costs due to the general global commodity price inflation resulting from previous QE. Industries ranging from airlines to mining are facing industrial action as workers push for wage increases. These factors are beginning to place pressure on profit margins.

But now, already facing margin pressure, corporations might need to contend with unforeseen trade barriers springing up right in the middle of their highly specialised, globalised operations. These may have a huge impact on their cost structure and in some cases will render entire divisions uneconomic. Large restructurings may be required, costly as they are. Some corporations may find that they are simply unprofitable absent free trade and will wind down operations or possibly even end up in bankruptcy. Shareholders may be in for a rude shock.

At a minimum, the equity risk premium is likely to rise in the event that it appears that the currency wars are morphing into trade wars. That will depress valuations. At worst, the global equity market might crash. Indeed, some economic historians believe that the proximate trigger for the great stock market crash of October 1929 was news of a major compromise in the US Senate making it highly likely that the proposed Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act would pass [6]. Of course, the world was hardly as globalised back then.

Just imagine what effect something along the lines of Smoot-Hawley would have today.

[1] At only 63.5%, the labour market participation rate has declined back to where it was in the early 1980s, when a considerably smaller proportion of women worked full-time.

[2] Please see Fighting Solvency Time Bombs with Liquidity Bazookas, Amphora Report Vol. 2 (October 2011).

[3] That new money entering the economy benefits primarily those who first receive it is hardly a novel idea but it is one that neo- Keynesian economics conveniently glosses over. Economist Richard Cantillon recognised the ‘non-neutrality’ of money way back in the 18th century and the way in which new money distorts relative prices is called the ‘Cantillon Effect’.

[4] Fed Chairman Bernanke stated as much in a (in)famous 2002 speech in which he discussed how central banks can always prevent deflation and create inflation if desired.

[5] Begun, The Currency Wars Have, Amphora Report Vol. 1 (October 2010).

[6] The US House of Representatives passed a version of the Smoot- Hawley bill by nearly a 2/3 majority in May 1929. It was assumed at that time, however, that the bill was unlikely to get through the Senate, and the stock market continued to rise. Indeed, even following much debate and compromise, the Senate’s version of the bill passed by only the narrow margin of 44 to 42.

This article was previously published in The Amphora Report, Vol 3, 2 October 2012.

Some of the problems that John Butler sees are imaginary. A general rise in demand would enable more debtors to pay off their debts, IF THAT’S what they wanted to do. But negative equity folk apart, they might not want to. And my response is: what of it?

If someone with a big mortgage can pay the interest on the mortgage and wants to continue that way, I don’t see the problem.

As to high corporate debt, corporations also have cash piles of record proportions, so there is no big problem there.

Re Butler’s claim that reflation would erode debts, I don’t favour reflation (i.e. an increase in demand) of sufficient size to let inflation get excessive (although Kenneth Rogoff favours that policy). If it’s possible to reflate WITHOUT excessive inflation, then we should go for it.

Re Butler’s objections to “putting fresh capital in the hands of those who misallocated it in the past”, I quite agree. And wouldn’t you know it, that’s exactly what central banks have done, or tried to do in that they’ve cut interest rates to record lows? That will tend to boost asset price bubbles. Just can’t get anything right, can they?

If increasing demand without inflation is possible, then simply creating new money and spending it into the economy (and/or cutting taxes) is the best option (as advocated by for example Positive Money and Modern Monetary Theory). As to interest rates, they should be left to find their own free market level.

I am not sure why you state:- “Globalisation, as it were, begins to go into reverse. While the neo-luddite, anti-globalisation crowd might rejoice at this development..”

Perhaps the anti-globalisation crowd saw that what was being portrayed as ‘Globalisation’ was in fact the purposeful destruction of Western Economies and currencies for the benefit of Banking Empires – (‘Empires’ being the opposite to ‘Nationalism’ – You can have friendly nationalism where you respect thy neighbour, engage in free trade and assist them should they be attacked – they are your customers, after all! You cannot have friendly Empire as it is coercive, oppressive and violent in nature).

All of what is written in this website and others is in despair at the the result the anti-globalists feared. I think you will agree we would have been better of without Globalisation or you agree with the less than satisfactory result obtained?

Organic Globalisation through supply and demand is perfectly acceptable and was more the world prior to the Clinton/Greenspan money supply expansion.

I am reminded of The Media, Politicians and Keynesian Economists saying it was unchecked ‘Capitalism’ that caused the crisis, when we here know it was Central Planners (politicians who were ex employees or soon to be employees of banks) ‘forcing’ banks to loan to those who were a bad risk and the banks, requiring some concrete guarantee for this folly, saw an opportunity to take advantage of the tax payer guarantee to make good all of the losses.

For anti-globalists to be luddites would imply that Austrian School Economists are also luddites. I think both are fully vindicated. Dont you?

I can understand why people vote for Socialism when confronted with Corporatism/Privatisation and vice versa. Neither are productive or honest. How can we free marketeers win the arguments against both and yet lose the debate to bring about a free market?

I share your concerns. The key is semantics. The mainstream portrays socialism as the only alternative to corporatism. They either conveniently ignore the Austrian, free-market alternative or wrongly conflate it with corporatism. The most powerful response to this rhetorical trick is to promote the concept of voluntary human action as the source of both sensible economic policy and morality. That which is coerced can be neither sensible economically nor moral.