There were a lot of commentaries regarding the Ireland and Iceland 2008-12 financial crises. Most of the commentaries were confined to the description of the events without addressing the essential causes of the crises. We suggest that providing a detailed description of events cannot be a substitute for economic analysis, which should be based on the essential causes behind a crisis. The essential cause is the primary driving force that gives rise to various events such as reckless bank lending (blamed by most commentators as the key cause behind the crisis) and a so called overheated economy.

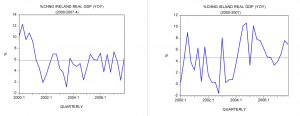

Now in terms of real GDP both Ireland and Iceland displayed strong performance prior to the onset of the crisis in 2008. During 2000 to 2007 the average growth in Ireland stood at 5.9% versus 4.6% in Iceland. So what triggered the sudden collapse of these economies?

Central bank policy the key trigger for economic boom

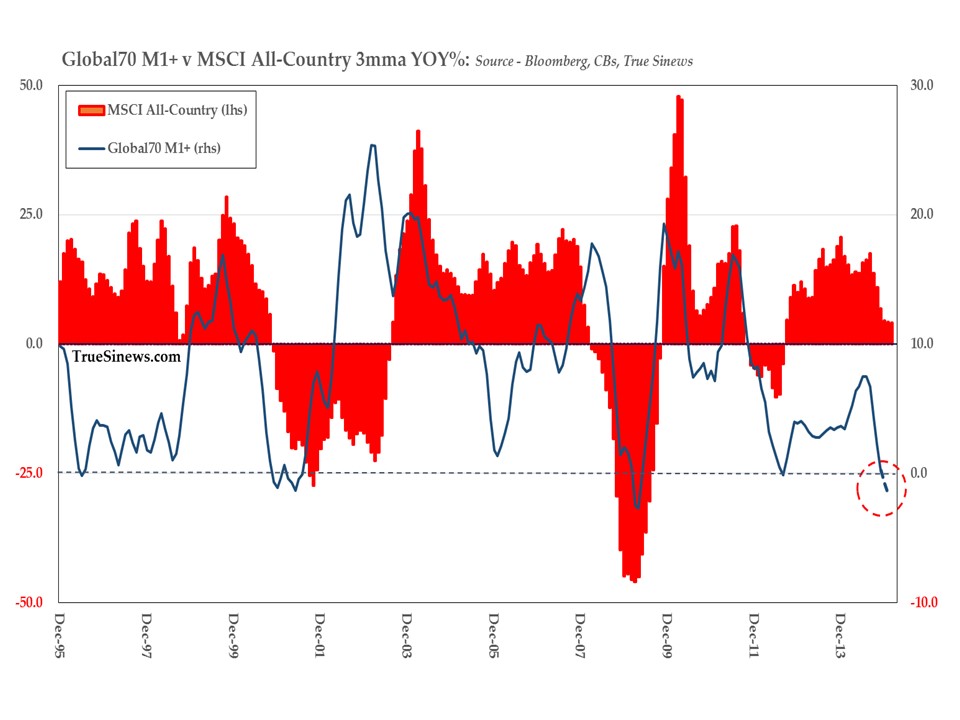

What set in motion the economic boom (i.e. a strong real GDP rate of growth) in both Ireland and Iceland was an aggressive lowering of interest rates by the respective central banks of Ireland and Iceland. In Ireland the policy rate was lowered from 13.75% in November 1992 to 2% by November 2005. In Iceland the policy rate was lowered from 10.8% in November 2000 to 5.2% by April 2004.

In response to this, bank lending showed a visible strengthening with the yearly rate of growth of Irish bank assets rising from 7.4% in June 2002 to 31% by November 2005. In Iceland the yearly rate of growth of bank lending to residents climbed from 26.5% in September 2004 to 57.8% by April 2006.

The growth momentum of money supply strengthened visibly in both Ireland and Iceland. The yearly rate of growth of our measure of money supply (AMS) for Ireland jumped from minus 6.7% in March 2003 to 22% by March 2006. In Iceland the yearly rate of growth of AMS climbed from minus 1.6% in January 2003 to 61.6% by June 2004 before closing at 47.7% by July 2004.

The aggressive lowering of interest rates coupled with strong increases in the money supply rate of growth gave rise to various bubble activities. (The central bank’s loose monetary stance set in motion the transfer of wealth from wealth generating activities to non-productive bubble activities).

Central bank policies trigger economic bust

On account of strong increases in the money supply rate of growth a visible strengthening in price inflation took place in Ireland and Iceland. In Ireland the yearly rate of growth of the consumer price index (CPI) rose from 2.9% in January 2006 to 5.1% by March 2007. In Iceland the yearly rate of growth of the CPI jumped from 1.4% in January 2003 to 18.6% by January 2009.

To counter the acceleration in price inflation the central banks of Ireland and Iceland subsequently tightened their stance. The policy interest rate in Ireland rose from 2.25% in January 2006 to 4.25% by July 2008. In Iceland the rate shot up from 10.2% in January 2006 to 18% by February 2009. Furthermore, the pace of money pumping by the central bank of Ireland fell to minus 8.2% by July 2007 from 25% in January 2007. The pace of pumping by the Iceland’s central bank fell to 43% by February 2008 from 123% in July 2006.

The yearly rate of growth of AMS in Ireland plunged from 32% in August 2009 to minus 30% by November 2011. In Iceland the yearly rate of growth of AMS fell from 96% in October 2007 to minus 18% by September 2009.

The sharp fall in the growth momentum of money supply coupled with a tighter interest rate stance put pressure on various bubble activities that emerged on the back of the previous loose monetary policy stance.

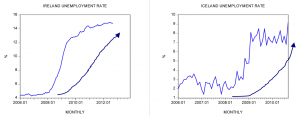

Consequently, various key economic indicators came under pressure. For instance, the unemployment rate in Ireland rose from 4.4% in January 2006 to 14.9% by July 2012. In Iceland the unemployment rate climbed from 2% in January 2006 to 9.2% by September 2010. Year-on-year the rate of growth of Irish real retail sales fell from 3.8% in January 2008 to minus 25% by September 2009. In Iceland the yearly rate of growth of real retail sales fell from 11.9% in Q1 2008 to minus 31% by Q1 2009.

Most commentators blame the crisis on the conduct of banks that allowed the massive expansion of credit. It is held that this was responsible for the massive property boom in Ireland and to overheated economic activity in Iceland.

We hold that the key factor in the economic crisis was the boom-bust policies of the central banks of Ireland and Iceland. Loose monetary policy had significantly weakened the economy’s ability in both Ireland and Iceland to generate wealth. This resulted in the weakening of various marginal activities. Consequently, a fall in these activities followed by a decline in the pace of lending by banks and this in turn coupled with a tighter stance by central banks set in motion an economic bust. With the emergence of a recession, banks’ bad assets started to pile up and this in turn posed a threat to their solvency.

From May 2007 the banks’ stock prices on the Irish stock market declined markedly – they had halved by May 2008. This had an inevitable effect on banks capital adequacy ratios and therefore their ability to lend ever higher amounts that were necessary to support property prices.

As a result house loans as % of GDP plunged from 70.5% in Q2 2009 to 49.2% by Q2 this year. At the height of the boom a fifth of Irish workers were in the construction industry. The average price of a house in Ireland in 1997 was 102,491 euros. In Q1 2007 the price stood at 350,242 euro’s – an increase of 242%. The average price of a home in Dublin had increased 500% from 1994 to 2006.

Now in Iceland at the end of Q2 2008 external debt was 50 billion euros, more than 80% of which was held by the banking sector – this value compares with Iceland’s 2007 GDP of 8.5 billion euro’s. The liabilities of the three main banks were almost 10 times the size of the Iceland’s GDP.

With the emergence of the bust, Icelandic authorities allowed its banks to go belly up whilst the Irish government decided to support the banks. According to estimates the cost to the taxpayers of providing support to Irish banks stood at 63 billion euros. (The private debt of the failed banks was nationalized). In Iceland the government, by allowing Icelandic banks to fail, made foreign creditors, not Icelandic taxpayers, largely responsible for covering losses.

The fact that Iceland allowed the banks to go bankrupt was a positive step in healing the economy. Unfortunately Iceland introduced a program of safeguarding the welfare of the unemployed. Also, the collapse of the Icelandic Krona hit hard homeowners who borrowed in foreign currency.

In response to this the authorities orchestrated mortgage relief schemes. Iceland has also imposed draconian capital controls. Obviously all this curtailed the benefits of allowing the banks to go belly up.

Whether the Icelandic economy will show a healthy revival, as suggested by some experts, hinges on the monetary policy of the central bank. We suggest the same applies to Ireland. (What is required is to seal off all the loopholes for the creation of money supply).

Bad policies are coming back

For the time being in Iceland the yearly rate of growth of AMS jumped from minus 11.3% in May 2010 to 34% by May 2012. Also, in Ireland the growth momentum of AMS is showing strengthening with the yearly rate of growth rising from minus 30.3% in November last year to 4.7% in September 2012.

The rising growth momentum of money supply is a major threat to sound economic recovery in both Ireland and Iceland.

Also note that the policy interest rate in Ireland fell from 1.5% in October 2011 to 0.75% at present. In Iceland the policy rate was lowered from 18% in February 2009 to 4.25% by July 2011. All this sets again in motion a misallocation of resources and new bubble activities and in turn economic impoverishment.

Summary and conclusion

Many commentators blame reckless bank lending as the key cause behind the 2008-2012 Ireland and Iceland financial crises. Our analysis, however, suggests that it was not the banks as such that caused the crisis but rather the boom-bust policies of the central banks of Ireland and Iceland. It is these institutions that set in motion the false economic boom and the consequent economic bust. Whilst Iceland allowed its banks to go bankrupt the Irish government chose to bail out its banks. So in this sense the Icelandic authorities did the right thing. We hold that despite this positive step, Iceland’s authorities have introduced various welfare schemes which have curtailed the benefits of letting banks go belly up. Furthermore, both Ireland and Iceland have resumed aggressive money pumping thereby setting in motion the menace of boom-bust cycles.

Interesting.

‘Most of the commentaries were confined to the description of the events without addressing the essential causes of the crises’…. It is as important to publicise the establishment techniques for saying nothing with as many words as possible so everyone gets it. Great article.

In addition to above-mentioned it could be added that central bank should not be credited with such an extensive influence over economic misfortunes in the Iceland. Following analysis of P.Bagus and D.Howden several other reasons the financial sector expanded so rapidly could be added. Without government fiscal policies, guarantees and subsidies, and boom in a particular sector does not occur.

In Iceland government guarantees on the debts of state agency “Housing Financial Fund” without fiscal restrictions in housing markets triggered unsustainable growth in this sector.

And the Icelandic central bank could not on its own sustain such a strong increases in the money supply rate which gave rise to various bubble activities. The Bank of Japan had pursued a loose monetary policy and Japanese-yen-denominated loans was an important source of external funding for the Icelandic central bank. Yen-denominated loans provided large amount of short-term liquidity which was invested into long-term projects.

Bust in the commercial housing market caused maturity mismatching – short-term loans used to finance housing construction and other long-term business activities could not be renewed and when become due could not be returned. The situation turned out more severe as a result of currency mismatching because foreign currency denominated short-term loans on the balance sheet of the central bank could not be repaid with printing-press produced local currency.