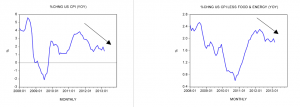

The Federal Reserve Board originally led us to believe that it was necessary to expand money supply through quantitative easing to offset the contraction of bank credit. Bank credit is no longer contracting, and indeed was already expanding when QE3 was introduced. This objective is now being satisfied as illustrated in the chart below:

Perhaps helping to drive this trend is a fall in the general level of charge-off and delinquency rates to less than 1.5% of all loans and leases, down from the crisis levels of twice that. According to an article at Bloomberg dated August 6, “…. households have cut debt since the 2008-09 crisis, while banks have increased liquidity and bolstered capital buffers”. So the up-coming fiscal cliff permitting, conditions are in place for a further expansion of bank credit and we can put the past behind us.

Well, not quite.

As well as conventional bank lending, there is also shadow banking to consider. The Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report 2012 tells us that at $23 trillion for the US alone, it dwarfs reported bank lending. According to Exhibit 3-3, before the banking crisis, shadow banking in the US was growing at a compounded annual rate of over 10%, and subsequently has contracted slightly. But this probably masks a more recent pick-up in the growth rate in line with on-balance sheet bank lending, and we must also take into account the far greater growth in shadow banking in non-US financial centres, particularly in the UK, Hong Kong, Singapore and Switzerland, where restrictions on re-hypothecation are often less onerous.

The problem with this elephant-in-the-room is that shadow banking requires no bank capital to back it, because it works on collateral pledged by non-bank institutions and the general public. It is comprised principally of securitised consumer property loans and mortgages, as well as sovereign debt. And because the global financial system is fully integrated, the $22 trillion equivalent that is the eurozone’s exposure to shadow banking must also be seen as a significant risk: no wonder the European Central Bank has signalled it will save the eurozone in its entirety, at all costs. This is also interest rate sensitive stuff, and with no capital buffers to absorb losses it will not take much of a rise in rates to trigger a crisis, even without an external shock.

Now consider what happens if interest rates are forced upwards by the economic recovery, clearly signalled by the bank lending statistics in the chart above. The value of this collateral will fall, and anything more than a modest interest rate increase will risk collapsing the entire financial system. The Fed, along with the other central banks is effectively trapped: it can no longer manage the money supply in accordance with its mandated objectives. It is now the Fed’s primary function to worry about shadow banking, over which it has no direct control, other than to make sure sufficient collateral of good quality continues to be available.

There is a worrying complacency in financial circles about this problem, which suggests that financial assets are not discounting the serious risk of systemic failure. It demands serious attention.

This article was previously published at GoldMoney.com.

QE achieved its objective – the relection of Barack Obama.

If one has political money – one has money dominated by political concerns.

As for 2013 (and beyond) the Fed (and the establihsment generally) do not care about 2013. Nominal Democrats or nominal Republicans – it does not matter, the Central Banking crew wanted Barack too win and they were prepared to do anything (anything at all) to achieve that objective.

They will have their celebration on January 20th – then, after that, everything falls apart.

And they do not really care.

What are the implications of this for financial centres like Switzerland and Singapore?

Hello John

Shadow banking has grown in all international financial centers. It is a global systemic risk.

Switzerland has (via its Central Bank) tied itself to the Euro.

However, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein, are more than “fiancial centres” – they are diverse economies (I suspect that they will fair better than many places).

Singapore – well again there is a lot more to Singapore than banking and so on.

However, (yes) banking and finance are total mess – all over the world.

I am not even sure what all that money in the government controlled investment fund in Singapore is invested in.

It’s completely absurd to have bank regulations and limit the regulations to institutions which have the word “bank” emblazoned over their front doors, while ignoring institutions which do what banks do, but don’t admit to being banks.

However, it seems our dozy old regulators have at last tumbled to this. Lord Turner of the FSA recently said, “If it looks like a bank and quacks like a bank, it has got to be subject to bank-like safe-guards.”

The trouble with (or one of the troubles with) regulations is that the powers-that-be tend to want to the banks (and bank-like-entities) to do the very things that get them into trouble – then the governments and Central Banks scream “if only we had wider powers this would not have happened”.

Even now they are calling on banks to “lend more” and “lend on less harsh terms”.

The only way to put some breaks on the “bank like entities” is to get rid of (not strengthen) Central Banking – and make sure they know that if they get into trouble they will GO BANKRUPT.

Real bankruptcy – not managed bankruptcy.

For example, AIG should not have bailed out.

And if that mean that Goldman Sachs (not then officially a bank) went down……

GOOD.

This whole system is rotten – rotten to the core.

The size of the entire financial services industry should be roughly the same size as the percentage of real savings.

For example, if people (on average) save about 10% of their income than the financial services sector should be about 10% of the economy. This OF COURSE is a very rough “rule of thumb” thing. And nations that attract real savings from other countries will have bigger financial services sectors.

However……

These bank-like-entities alone are 370% of GDP in Britain and 210% of GDP in Switzerland.

They are bigger than the entire economy – and that is just the bank-like-entities (not the entire fiancial services industry).

See why I am not interested in this-or-that policy change?

The financial services sector is absurdly oversized.

The international economy has become a vast bubble.

And it will go.

Of course the gap is not as extreme as it might first appear – the financial system should deal with all real savings (not just the real savings of any particular year).

However, there is still a vast size gap between the size the financial services sector (all of it – not just the bank like entities) and the size it should be. The bubble economy is vast.