Continued from Part 1 …

To recap the lesson we have drawn here: if there is a great urgency about demand for the means of end-consumer satisfaction – whether this ‘hunger’ is for actual sustenance or for an arguably less necessary smart phone, or a non-functional, yet pleasure-giving, work of art is of no major consequence here – the compensation exacted for resisting that urgency (that time preference, as we say) will be greater. It is straightforward to infer from this that the ratio of prices between present and future goods will be higher and hence that the discount separating them will be wider – that is to say the undistorted rate of interest will be more elevated; this elevation being a direct consequence of the heightened degree of scarcity being attached in general to these end-consumer goods.

Should that urgency be lower – either because the underlying appetite for such end-goods has been lessened on social or cultural grounds, or because an unchanged demand has been more fully satisfied through being more amply provided – things will move in the opposite sense. Those rarae aves who manage to exert a greater control over both the rumblings of their stomachs and the momentary temptations of the deadlier sins will therefore be more willing to set aside their own demands and thus be more inclined to ask a lower fee in recompense for the postponement. Those who already have more of whatever it is they want, will also find the marginal utility of the next increment somewhat lower and will also be more readily persuaded to do without it. In each case, time preference is reduced, interest rates are lowered, and the earlier contributions to the flow of final goods are relatively less discounted – in a word, consumption is reduced and saving accordingly increased.

This at once allows for more time-consuming, more capitalistic, more roundabout methods of production to be safely introduced. [As an aside, the notion of being more time-consuming does not just mean that we all have to forego crossing the river in the small groupings dictated by our modest ferry’s capacity while we toil for years to erect a six-lane suspension bridge between its banks, but rather that the invested process needs extra turns of the productive cycle to reimburse its outlays, even if the ongoing delivery of services to the consumer it is actually speeding up under its operation]

It should not go unremarked here that the second set of people – the ones enjoying a relatively profuse supply – will soon be yet more prosperous, since their very wealth affords them the means with which to increase their capital endowment and so further to add to their riches. It will be their good fortune to find themselves spiralling gently higher in a virtuous circle. It might also be noted, however, before an invidious comparisons are drawn, that the first group, those who are merely disposed to be more thrifty than their fellows, no matter how poor they start out, have set themselves upon the same upward path and, hence, by maintaining their relative abstinence, they are, in fact, likely to enjoy a greater provision of goods – a higher income – over time than those of their fellows who succumb more readily to the promptings of the moment. Pace, Keynes and the Underconsumptionist school, it is saving that makes us rich, not spending, and it is only by saving – not through authoritarian fiat – that a naturally lowered interest rate confers a lasting aid to capital formation.

From the principle already laid out above, we recall that a good at an earlier stage of transformation – anywhere from the first, crude offerings of nature to the last, often exquisitely-crafted ware in the shop window – not only derives its value from its discounted contribution to the latter’s ultimate purchase, but, where such an early-stage good is adaptable enough to be put to multiple uses, from each and every competing end to which it might be put (as well as to such, as yet only imagined, end goods as the innovating entrepreneur can envisage selling where none has ever been sold before). It should therefore be plain that any falsification of the market rate of interest, any provision of ‘fictitious capital’ beyond the actual saving being undertaken must disrupt the fabric of this subtle web of pricing-by-imputation. From such a dislocation, no good thing can be generally expected to result – which is not entirely to rule out the happenstance that the occasional businessman might be either lucky enough to achieve success in spite of this, or exceptional enough in his original conception that his product becomes so sought after that it re-forges these links in his favour.

It should be all too apparent by now that if we are to enjoy conditions which are favourable to both the greatest degree of co-ordination between the market’s multitude of actors; if we are to remove all impediments to the early recognition of such lapses from that co-ordination as must inevitably occur in a shifting world of imperfect knowledge and changing tastes, then any interference with the spontaneous, holistic formation of prices is not to be countenanced, much less embraced as a tool of dirigisme. Rather, it is vital that the myriad interactions between buyer and seller, producer and consumer, saver and spender, employer and employee should be allowed to make its due contribution to the universal field of prices thence to reveal how best to marshal our limited resources in order to deliver more of what appears to be the more urgently required and to expend fewer efforts on the less. This is not true only in the here and now, but also over time.

We hardly need labour the point that the surest way to breach these guidelines, to progressively misdirect human endeavour, and to squander hard-won capital is to adulterate the quality of that one unavoidable good which exchanges for every other – namely, money. Nor should a further rehearsal of our argument be required that the provision of an artificial, ‘fictitious’ credit introduces a dangerous level of unreality into the reckoning of the size of the social surplus – the ‘pool of real savings’ or the ‘subsistence fund’ – which is intrinsic to the naturally-arising interest rate. The scramble for fulfilment which this unleashes will eventually turn what first seems like a triumph of financial ingenuity over the hidebound possibilities of human parsimony into a disastrous diversion of much of the available means into the construction of what will to turn out to be white elephants, sub-marginal businesses, money pits, bail-out candidates, and outright failures when the inapposite nature of their foundation finally catches up with them.

It is almost trite to note that, empirically, most busts are associated with a collapse in either or both of the property market or the manufacturing/capital goods sector. Sometimes an implosion here drags the sector’s financiers along with it into ruin: sometimes the unsustainability is first made known by means of a banking panic or a stock market crash, with the frailty of the non-financial sector only slowly emerging thereafter as the inevitable reassessment of risks takes place and as access to external funds becomes correspondingly more straitened.

In the good old days, the trigger was often a balance of payments crisis. Fictitious credit at first found its way into the hands of producers but inevitably trickled down into the hands of the so-called ‘original factors of production’ – workers, landlords, and resource owners. Given that they had not willingly changed the balance of their preferences away from consuming on their own behalf to transferring more of their purchasing power to the expanding producers, a greater volume of such monies would begin to chase a basket of goods whose supply had not been expanded (since capital deepening is always a much more likely result of the credit boom than is capital widening when rates are lowered). More money meeting the same offering of goods (possibly a shrunken one, if the boom industries have really been effective in bidding away inputs) implies higher prices. In an open economy, elevated home prices encourage imports and discourage exports. Gold (or foreign exchange) flows out, the reserve base of the banking system is threatened, credit is contracted, a flight to money-proper sets in, and the bust ensues.

Though long-since removed from the bracing discipline of the gold standard, something of the kind can still be observed in the many developing nations which have sporadically become overly reliant on hot-foreign inflows. When these suddenly turn to self-accelerating outflows as the above effects kick in, what is now termed a ‘sudden stop’ occurs and the whirling carousel of created credit shudders jerkily to a halt, scattering its riders neck over crop around it.

More generally, today’s larger nations do not suffer such immediate constraints (we are back to Rueff’s ‘deficit without tears’ again) and they may have their policymakers lulled into inaction by managing to limit the initial rise in the price of consumables through an increase in their uptake of imports, especially where these are quoted by their vendors in capped, or barely appreciating, exchange rates. This has the effect of temporarily disguising the woes, even as it insidiously spreads the mischief.

Often the nation which is the source of the imports will attempt to absorb the receipts by expanding its own money supply in lockstep (a choice which leads both to domestic consumer price rises and to widespread malinvestments of its own). Inevitably, it finds itself financing more and more of its customers’ purchases, in a kind of reverse ‘forced-saving’. If not, its citizens are deceived by the relative lack of currency risk into accepting perilous levels of credit risk instead and so engage upon recycling the funds which are pouring in by financing an expansion in the usually more lucrative, non-tradable sectors of a partner economy which is actually crying out for more export-competing and import-substituting capacity. Alas, this latter influx will all too readily stimulate – or, where already ignited by home-grown policies, intensify – an unremunerative property market boom.

The reason these two sectors – capital goods and property – are frequently the most visible casualties of systemic misallocation is that they either generate a cash flow in packets which are greatly extenuated in time or, in the case of residential real estate, are actually negative, once the Ponzi gains resulting from rising prices start to evaporate. As we have already seen, the main source of vulnerability is that such higher-order, more capital-intensive undertakings take longer to earn their keep and to amortize their initial financial commitment (they are more ‘roundabout’, you have heard us say), Because of this, the re-assertion of consumer preferences – that resumption of command over such resources as were temporarily lost to the Cantillon (or injection) effects of the initial, producer-oriented, credit expansion – can take place at any point along a timeline which stretches far out into the uncertain future. However deferred may be its dawning, when that day arrives, it will shift the matrix of relative prices and scheduled resource availability to the severe disadvantage of the malinvested schemes, frustrating the profitable conclusion of many of them.

Continue to Part 3.

We are long past the “if” things will go into decline stage (things have gone way beyond the point of no return) the question now is “when?”

British manufacturing output appears to be already in decline (GDP is, of course, a terrible measure of the economy – counting govenrment spending as if it was a positive).

But will this continue? And will American manufacturing also go into decline?

I will stick my neck out and answer “yes” to both questions.

In theory the demented credit bubble antics of the Central Banks could keep the farce on the road for some time yet – but I do not think it will.

I think that output in 2013 (both in Britain and the United States) will be lower than in 2012, and I think that output in 2014 will be lower than in 2013.

As all the banking (and other) plans are based on their being some sort of real “recovery” in 2013 (and so on) I think that the financial system itself will begin to go into terminal decline.

“Never predict – never tie yourself down to dates”.

Too late – I just have.

That is a great 2,000 word display of flowery language and hyperbole by Sean Corrigan. Moving on the economics….

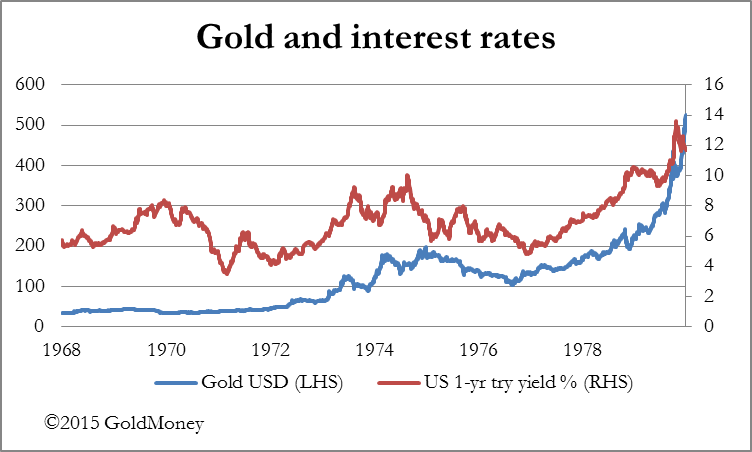

His basic point is that artificial interference with interest rates distorts the market and reduces GDP. There you are – I made the point in sixteen words rather than 2,000.

But there are reasons for discounting Corrigan’s undoubtedly correct point. For example anyone with their head screwed on funds long term investments with long term loans (or equity), to which extent they are insulated against interest rate rises.

Also there are numerous costs associated with any investment other than the interest paid to fund the investment (e.g. labour costs, energy costs, depreciation etc). Thus in many cases a 2% change in interest rates for example has a negligible effect on the total cost of running the investment. I.e. Sean’s “mal-investments” will in many cases not be all that “mal”.

I could have used two thousand words to make each of the above two points, but I just don’t have the time.

As for the idea (advocated by Westminster politicians and central bank officials) that the best way to escape a recession caused by excessive and irresponsible lending is to cut interest rates so as to re-inflate asset bubbles and re –introduce the irresponsible lending, I dearly wish all those advocating that policy could be carted off to the funny farm.

Ralph,

He is writing as simply as he can for you, cut him some slack.

John