Is reserve currency status an economic blessing or a curse? The answer might seem obvious, as reserve currencies have been shown to confer lower borrowing costs on their issuers. But what of the borrower who, enticed by low interest rates, borrows more than they can pay back? Naturally the result will be a default. However, for the issuer of a reserve currency that is unbacked by a marketable commodity, such as gold, in the event that they borrow too much, they can just print more currency. While this avoids default indefinitely, it also hollows out the economy, erodes the capital stock, reduces the potential growth rate and, eventually, leads to a dramatic devaluation of the currency and loss of reserve status. History has not been kind to countries that have followed this path. In my view, the grave investment risks associated with the US dollar’s inevitable and potentially imminent loss of reserve status are not priced into financial markets.

RESERVE CURRENCIES, TRADE IMBALANCES AND THE ‘TRIFFIN DILEMMA’

Having written a book about international monetary regime change past, present and future, I weigh in again in this Amphora Report on what is gradually becoming a more mainstream debate about whether or not the US dollar is at risk of losing reserve currency status; what currencies might replace it; and, should it happen, what general economic and financial market implications this would likely have.[1]

As it happens, I have a rather strong opinion on all of these matters. But first, let’s consider what a reserve currency is and what it is not. Second, let’s distinguish carefully between reserve currencies that are backed by a marketable commodity, such as gold or silver, and those that are not. Third, let’s take a look at shifting global economic power and monetary arrangements. Then we can move into what I think is going to happen in future, what this implies for financial and commodities markets, and what investors can and should do to prepare.

What, exactly, is a reserve currency? It is an international money that is used to pay for imports from abroad and is then subsequently held in ‘reserve’ by the exporting country, as it does not have legal tender status outside of its country of issuance. In the simple case of two countries trading with one another, with one being a net importer and one a net exporter, over time these currency ‘reserves’ will accumulate in the net-exporting country. In practice, as reserves accumulate, they are invested in some way, for example, in bonds issued by the importing country. In this way the currency reserves earn some interest, rather than sit as paper scrip in a vault.

Beyond a certain point, however, accumulated reserves will be perceived as ‘excessive’ by some in the exporting country, in that they would prefer to purchase something with this accumulated savings instead. In this case they have a choice: either they can purchase more imports from the net-importing country, thereby narrowing the trade imbalance, or they can exchange their reserves with another entity at some foreign-exchange rate. For this reason, other factors equal, as reserves accumulate, the reserve currency will depreciate in value.

As trade imbalances and reserve balances grow, so does the natural downward pressure on the value of the reserve currency as described above. This leads to what Belgian economist Robert Triffin called a ‘dilemma’: for unbalanced trade to continue to expand, the supply of reserves must increase. Yet this implies a chronically weak reserve currency, which leads to price inflation. Indeed, under the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, the supply of dollar reserves grew and grew, price inflation increased and, eventually, as one European central bank after another sought to exchange its ‘excess’ dollar balances for gold, this led to a run on the official US gold stock and the demise of that particular monetary regime.

While hailed as an important insight at the time, Triffin was pointing out something rather intuitive: Printing a reserve currency to pay for net imports is akin to owning an international ‘printing press’, the use (or abuse) of which causes net global monetary inflation and, by association, some degree of eventual, realised price inflation.

‘CANTILLON EFFECTS’ AND THE NON-NEUTRALITY OF INTERNATIONAL RESERVES

Now let’s combine Triffin’s insight with that of Richard Cantillon, a pre-classical 18th century economist, that money is not ‘neutral’: new money enters the economy by being spent. But the first to spend it does so BEFORE it begins to lose purchasing power as it expands the existing money supply. The money then gradually permeates the entire economy, driving up the overall price level. Those last in line for the new money, primarily everyday savers and consumers, eventually find that, by being last in line for the new money, their accumulated savings are being de facto ‘diluted’ and the purchasing power of their wages diminished.

Extropolated to the global level, this non-neutrality of money implies that an issuer of a reserve currency is the primary beneficiary of the ‘Cantillon effect’. First in line for the new international money you have the owners of capital in the reserve issuing countries, who use the new money to accumulate more global assets, and at the end you have workers the world over who receive the new money last, after it has placed general upward pressure on prices. Greater global wealth disparity is the inevitable result.

Another way to think about the benefits of issuing the reserve currency is that it generates global seignorage income. Federal Reserve notes pay no interest. However, they can be used to purchase assets that DO bear interest. No wonder the Fed always turns a profit: it issues dollars at zero interest and collects seignorage income on the assets it accumulates in return.[2] But in a globalised economy, with the US a large net importer and issuer of the dominant reserve currency, this seignorage income is partially if indirectly sourced from abroad, via the external accounts.[3]

This becomes particularly notable in the event that domestic credit growth is weak relative to abroad. The Fed may print and print to stimulate domestic credit growth but if that printing does not get traction at home, it will instead stimulate credit growth abroad and, eventually, contribute to higher asset and consumer price inflation around the world.

Over time, this will impact the relative competitiveness of other economies, where nominal wage growth is likely to accelerate, eventually making US labour relatively more competitive. That may sound like good news, but all that is really happening here is that US wages end up converging on those elsewhere, something that should happen in any case, over time, between trading partners as their economies become more highly integrated. But to the extent that this wage convergence process is driven by reserve currency inflation, rather than natural, non-inflationary economic integration, the Cantillon effects discussed earlier result in wages converging downward rather than upward, implying a global wealth transfer from ‘owners’ of labour—workers—to owners of capital.

So-called anti-globalists disparaging of free trade are thus not necessarily barking mad—well, perhaps some are—but they are barking up the wrong tree. The problem is not free trade; the problem is trade distorted by monetary inflation. If you want workers around the world to get fairer compensation for their labour, shut down the reserve currency printing press. And if you also want them to have access to the largest possible range of consumer goods at the lowest possible cost, remove trade restrictions, don’t raise them.

RESERVE CURRENCIES: GOLD-BACKED, AND UNBACKED

Prior to the First World War, the bulk of the world was on the classical gold standard. Although the British pound sterling was the dominant reserve currency, it was not possible to print an endless amount of pounds to pay for endless imports, as external reserve currency balances were regularly settled in gold. The British pound thus held its value over time, as did other currencies on the gold standard, and there was not a ‘Triffin Dilemma’ resulting in growing, unsustainable trade imbalances. Moreover, absent monetary inflation, there were no insidious Cantillon effects taking place. Industrial wages were generally stable through these decades, which were characterised by mild consumer price deflation. This implied an increase in workers’ purchasing power and standards of living. So while there are certain similarities between sterling’s previous, gold-backed role as a reserve currency and that of the unbacked, fiat dollar today, there are even greater differences.

(For those curious how such a stable international economic order could break down so completely in such a short period of time, please turn to the extensive literature on the causes and consequences of WWI, arguably the greatest tragedy ever to befall western civilisation.)

Returning to the present, countries that have been exporting to the US and accumulating dollars in return are increasingly getting the joke, but they aren’t laughing. Hardly a week goes by without some senior official in an up-and-coming country rich in natural resources or with competitive labour costs criticising US monetary policy while suggesting that gold should play a greater role in international monetary affairs. The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, now joined by South Africa), individually and together, have already made numerous official, public statements to this effect.[4] One can only imagine what is being discussed in private, behind closed doors.

Recently, quite similar monetary concerns were expressed openly by Turkey, historically a ‘swing-state’ in its global orientation, yet currently a member of NATO and thus at least a nominal US ally. Prime Minister Erdoan, who is far more popular with the electorate in his country than most western leaders are in theirs, had this to say recently, in criticism of the International Monetary Fund (IMF):

The IMF extends aid on a who, where, how and on what conditions basis. For example, if the IMF is under the influence of any single currency then what, are they going rule the world based on the exchange rates of that particular currency?

Why do we not switch then to a monetary unit such as gold, which is at the very least an international constant and indicator which has maintained its honor throughout history. This is something to think about.[5]

Historians will note that once upon a time, France was a full member of NATO, but following President De Gaulle’s decision to challenge the dollar-centric Bretton Woods system in the mid-1960s, there erupted a series of dollar crises that culminated in the collapse of the Bretton Woods regime in the early 1970s. Is history about to repeat?

(Incidentally, history has already nearly repeated once before, in 1979-80. While the mainstream historical economic narrative about this period is that the Fed resorted to punitively high interest rates to fight the high rate of domestic price inflation, one look at the behaviour of the dollar in 1979-80 tells a different story, that the air of crisis at the time had an important international dimension. FOMC meeting transcripts also reinforce this arguably ‘revisionist’ view that the dollar’s reserve status was at risk.)

Clearly there is growing dissatisfaction with the current set of global monetary arrangements, which allow the US to print the global reserve currency to pay for imports, an ‘exorbitant privilege’ as it was termed by another French president, Valery Giscard d’Estaing. Under the Bretton Woods system, France, or any participating country for that matter, could choose to exchange its accumulated dollars for gold. As predicted well in advance by French economist Jacques Rueff, a contemporary of Robert Triffin, the eventual exercise of this choice to exchange dollars for gold by not only France but a handful of other countries led to a run on the US gold stock in 1971 and an end to the dollar’s gold convertibility.

THE RESERVE CURRENCY CURSE IN DISGUISE

Let’s now turn to the question posed at the beginning of this report. Is reserve currency status a blessing, or a curse? The answer may seem obvious. After all, isn’t it nice to hold the power of the global printing press? To enjoy relatively low borrowing costs? To possess the ‘exorbitant privilege’, as it were? On the surface yes, but what lies beneath?

As Lord Acton is purported to have said, power tends to corrupt. By corollary, absolute power corrupts absolutely. And to the extent that an economic power that is held nationally is exercised internationally, then the corruption thereof has a deleterious international economic impact.

In the case of an unbacked reserve currency, the ‘benefits’ of lower borrowing costs accruing to the issuing country appear to result in overborrowing and overconsumption relative to the rest of the world, eroding the domestic manufacturing base over time and widening the rich-poor gap to levels that are socially destabilising. Trade wars, currency wars or other forms of economic conflict are the inevitable result. In some cases, actual wars follow. In others, they don’t. But in all cases, the reserve currency curse is recognised only too late, when an economy begins consuming its own capital in a desperate and counterproductive attempt to maintain its previous standard of living. Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises described capital consumption as akin to “burning the furniture to heat the home.” Sure, it might work for a time, but what comes next? The floorboards? The walls? The roof?

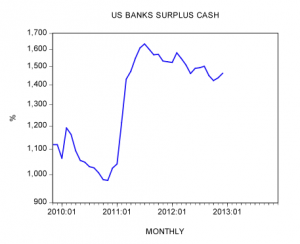

For those who think that a capitalist, free-market economy would never consume its own capital, outside of wartime, you may be right. But what of an economy that merely pretends to be capitalist and free market, but in fact sets the price of money by decree at an artificially low level so that there is little incentive to save? Well, take a look, this is what happens: Negative net investment!

US DOMESTIC INVESTMENT, NET OF DEPRECIATION, % OF GDP

It is highly intuitive to reason that, if an authority mandates a price ceiling below the natural, market-determined price for a given product, less of it will be produced and a shortage will result. Well here you see the empirical evidence: holding the ‘price’ of credit —the interest rate — artificially low over a sustained period of time leads to a shortage of savings, capital consumption and, therefore, a lower standard of living.

Notwithstanding basic economic common sense and clear evidence as presented above, the US Fed may still honestly believe that its neo-Keynesian models are right. Alternatively, like Galileo’s clerical inquisitors, it may be simply unwilling to admit that the models, or the entire theory, are wrong. The International Monetary Fund, for what it is worth, has already determined that its models are flawed, although they also admit they have little idea what to do about it other than to shoot in the dark, something that is not exactly reassuring.[6]

THE TURKEY IN THE GOLD MINE

Today, as the dollar is not convertible into gold, there could not be a run on the official US gold stock. But there is no reason why central banks around the world can not diversify out of dollars and into gold, something that would have much the same result: the dollar would decline versus gold and real assets generally, US imports would become more expensive and economic growth would be highly ‘stagflationary’, just as was the case during the 1970s, in the aftermath of a substantial dollar devaluation.

As it happens, these developments are already underway. According to recent reports, many central banks are accumulating gold, including Russia, China, Brazil, India, Bangladesh, Mexico, South Korea, Kazakhstan, Turkey and Indonesia.[7] While central banks must report their gold reserves to the IMF, the sovereign wealth funds of these countries are under no such obligation and, as sovereign wealth funds occasionally operate in effective if unofficial collaboration with their respective central banks, it is highly likely in my opinion that there is much more official gold accumulation taking place than is officially reported.

As they are not free-market, profit-maximising entities in the same sense as independent private investors, these official gold buyers are not as price sensitive. If they are instructed by their political leadership to diversify their reserves out of dollars in some amount, or at some regular rate, they are going to carry out that mandate, regardless of the price, until that policy changes. This is strategic, not tactical gold buying, as it were.

This is just one of many reasons why the gold price is going up. The most fundamental is simply that the values of currencies such as the dollar are going down as a result of endless quantitative easing (QE) or other forms of monetary expansion. That the agents swapping their dollars for gold happen in some cases to be price-insensitive official institutions is just one mechanism by which a global shift out of paper into hard assets is taking place.

I don’t pretend to know exactly what is going to happen from one day to the next. But when you step back and see the larger picture of one country after another expressing disapproval with the dollar reserve standard, you can’t help but notice that the game is changing. Central bank or other official forms of gold buying is but one aspect. Another is the growing official collaboration on monetary and other economic matters by the BRICS. Then there are the various bilateral currency arrangements between an increasing number of countries that allow them to reduce dependence on the dollar for bilateral trade.

At first glance, Turkey’s recent admission that it is paying for imports of Iranian natural gas with gold in order to avoid US sanctions may seem a small, insignificant development by comparison but within the larger context it could have a disproportionate impact.[8] Indeed, Turkey may be only one of several countries monetising gold for use in importing Iranian gas or other goods. As a canary signals danger in a coal mine, might Turkey be signalling something rather more significant for international monetary relations?

Quite possibly. Game theory is highly instructive as to how international policy regimes, once destabilised by changing conditions or incentives, can suddenly shift to, or collapse into, a new equilibrium, sometimes in response to seemingly insignificant developments. When countries that comprise in aggregate about 1/3 of all global trade flows express dissatisfaction with the dollar and the IMF, the current international monetary regime is clearly unstable. When a medium-sized player such as Turkey moves from one side of the game board to the middle, or to the other side, there is always a chance that this represents the proverbial ‘tipping point’ from one equilibrium to another. In this case, if history is a guide, then as the world moves away from the current, dollar-centric reserve standard system it will move to one based on mulitiple currencies, yet with some degree of explicit gold backing for major currencies.[9]

Why gold? Part I of my book, The Golden Revolution (available here), concludes with a discussion about why gold has by far the strongest claim to use as the future international monetary reserve replacement for the dollar. While historical precedent is important, there are also two important theoretical points to consider. First, there is no existing fiat currency alternative to the dollar at present, in the way that the US dollar provided an obvious alternative to the pound sterling following WWI. Second, given the increasingly obvious breakdown in cooperation in international monetary relations, it is highly unlikely that, as the dollar’s role diminishes, there could be a universal agreement about how to construct or implement a global currency alternative to the dollar. Yes, the IMF has proposed precisely this and (no surprise here) has put itself forward as the bureaucracy that could manage it, but as discussed above, Turkey, the BRICS and a handful of other nations don’t trust the IMF to act in their national interest. They apparently do trust in gold.

As a medium of exchange that cannot be printed or otherwise manipulated by any one country to somehow exploit another, gold holds more than just a historical claim to a future role as international money. It provides a basis for mutually-beneficial international trade when trust in monetary stability is lacking. The answer to the question of what currency or currencies can provide the future international reserve is thus as paradoxical as it is elegant: every currency, if linked to gold, and none, as gold itself provides the trust.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN FINANCIAL AND COMMODITIES MARKETS

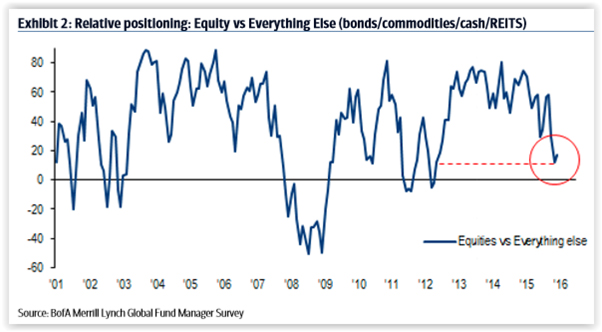

At time of writing, global equity markets have corrected modestly lower from the lofty valuations seen in early October. A series of corporate earnings disappointments and profit warnings was initially ignored but finally became so widespread across countries and industries that the selling pressure intensified sufficiently to reverse the big bull market that took place over the summer, in anticipation of yet another round of global monetary stimulus that arrived in September.

I expressed my concern with equity valuations back in October so I’m not exactly surprised by this development.[10] However, I am hardly omniscient and for all I know equity markets will begin to move right back up again for reasons that may have nothing to do with earnings, or profit expectations, or anything else that, in a normal world at least, would be expected to determine prices.

I have written variations on this theme many times but it seems entirely appropriate to revisit it again here: we do not live in a world in which financial asset prices are driven by sensible value judgements but rather speculation enabled and encouraged by policy makers in a growing number of ways. Applying a traditional, value-based investment approach in this environment is fraught with peril.

There are some things about which we can be relatively certain, however. If the dollar continues to gradually lose reserve currency status, or does so abruptly in a future financial crisis, it will reinforce the stagflationary economic conditions already prevailing in the US and in many other countries. Import prices will rise, yet growth will remain subdued given that the capital base is being consumed.

Of course there are things that US politicians could do to encourage savings and investment rather than consumption, but these things are politically unpopular. For example, neither of the two presidential candidates in the recent election advocated even a small reduction in the size of the federal budget, even though the deficit remains near record highs and the so-called ‘fiscal-cliff’ approaches. The ‘debate’ was so narrow relative to the vast scale of US economic problems that it seems a stretch to call it a ‘debate’ at all.

My impression is that the election was fought primarily on social issues. Now I don’t want to belittle those who feel strongly about social issues, but it seems a bit odd that these should determine the election result for the highest political office in a country founded on the principle that the federal government should stay out of social issues. One could be forgiven for thinking that the electorate is by comparision relatively unconcerned about the economy. I suppose Americans are schizophrenic, as many peoples seem to be.

Turning to Europe, I note that the political winds are now shifting decisively against those who would use the current crisis to centralise yet even more power in Brussels or in the ECB. This can be seen at both the regional level (eg Catalonia, Scotland) and the national (eg Greece, the UK, Ireland). At the margin, such sentiments make coordinated bailouts more difficult to implement. Although I am hardly supportive of bailouts for weak euro-area sovereign borrowers (or their lenders, if you prefer), if they are not forthcoming, this will deal a serious blow to European equity markets.

Speaking of political winds, there are also disturbing developments in France, where the government has recently threatened to nationalise corporate assets in the event that their owners seek to reduce capacity and fire workers in response to the economic slowdown well underway. This is not exactly going to attract foreign investment into the country. In any case, European economic growth is going to be unusually weak as long as the deleveraging continues, which might be rather a long time given the starting point.

I would like to remind readers that, during the stagflationary 1970s, major stock markets did not perform well. Yes, I know the conventional wisdom, that stock prices tend to rise with inflation, but then they can also perform rather poorly, in particular in real, inflation-adjusted terms.

Now it is the case that, in a historical comparision, stock market valuations in both the US and Europe are not particularly high. But really, given the context, why aren’t they particularly low instead? Sure in some countries, such as Spain, trailing P/Es and other classic valuation measures are essentially distressed, indicating good value. But today’s Spain is tomorrow’s… well, I don’t know. Pick a country, any country. There are plenty of candidates. So notwithstanding the modest correction of late I believe it is still too early for a general return to the equity markets.

Turning to bond markets, the outlook is inextricably linked to what happens with currencies, including of course the dollar. When a currency devalues for whatever reason, it takes its bond market with it. Yes, in practice it is not quite as simple as that, but when it comes to the most overpriced bond markets of today, such as those for US Treasuries, German Bunds, UK gilts or Japanese government bonds (JGBs), any devaluation in these currencies is likely to have an even greater impact on bond holders than on those sitting in cash instead. (That said, I believe there are pockets of value in distressed corporate debt and would recommend that readers familiarise themselves with some of the instruments available for getting some diversified exposure.[11])

Cash itself, of course, is at constant risk of devaluation, regardless of currency of denomination. Policymakers have made it abundantly clear that the value of cash is a policy tool, perhaps the single most important one there is. I regard it as highly unlikely that this thinking will change absent a future financial crisis that not only results in the death of the neo-Keynesian economic paradigm but also one that shows the current economic policy elite the door.

That leaves commodities. They may not be the stuff that powers Wall Street and credit creation but that is where the excessive leverage in the global financial system resides. Commodities cannot be arbitrarily diluted, devalued or defaulted on. They do not go bankrupt. They cannot be created by policymaker whim, although it is true that misguided regulations or price controls can create artificial scarcity, which is price supportive. That said, there is no certainty that commodity prices are going to rise, but if they don’t, this is unlikely to be the direct result of government action. Indeed, a general decline in commodity prices would be an indication that governments are finally backing away from inflationary policies, something that would, eventually, set the stage for a sustainable economic recovery built on savings, rather than on debt.

Well I’m not holding my breath. I fully expect governments to continue to implement misguided inflationary ‘solutions’ to economic problems themselves caused by inflation. And therefore I am over- rather than underweight commodities in my portfolio. Yes, some of these are likely to do better than others in the current global climate and I take that into account when managing positions. But much of investing remains a guessing game no matter what anyone tells you, including me.

The ultimate response to uncertainty, natural or man-made, is to diversify across a broad range of assets. What holds true for assets generally holds true for commodities specifically. I do have a soft spot for gold, but as all good traders know, emotions are distracting and dangerous. Fortunately, one doesn’t need to feel emotionally about gold to understand, entirely through logic and reason, that if the primary source of uncertainty in the world is the very future of money itself, then gold is likely to outperform in the event that such uncertainty continues to rise.

POST-SCRIPT: A BRIEF COMMENT ON RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE GOLD MARKET

As the topic of gold and gold investing has featured regularly in the Amphora Report, I am sometimes asked to comment on developments in the gold market. This has been unusually common of late, due to Germany’s decision to audit a portion of its gold holdings held abroad and Ecuador’s announcement that it will follow Venezuela’s initiative from last year and repatriate at least some portion of its gold reserves held in New York and London. (As an aside, don’t you ever find it ironic that those who shout the loudest that gold is but a ‘barbarous relic’ are those who live and work atop the bullion vaults under the NY Fed or the Bank of England, for example?)

Well, as it happens, I have long held that the act of physical repatriation of gold held on a custodial basis abroad is of more than just symbolic importance. As I wrote in an Amphora Report back in late summer 2011, following Hugo Chavez’s decision to repatriate Venezuela’s gold reserves:

Venezuela’s decision to take delivery of its gold places additional focus on the unique role that physical gold plays in the global economy. In recent months, the central banks of Mexico, South Korea, Bangladesh and Kazakhstan have bought gold on the open market. Others no doubt continue to accumulate gold less overtly. Why? If there was growing faith in the dollar-centric global financial system, would central banks be accumulataing gold reserves at the fastest pace since the 1970s?

No, on the contrary, this trend is a clear indication that global confidence in the dollar continues to erode. Should more countries line up to take physical delivery of their gold, rather than leave it in US custody, it would be a sign that confidence in the US itself, as a safe and reliable jurisdiction for global commerce, is also beginning to erode.[12]

Are we to interpret recent developments in the gold market as signs that “confidence in the US itself, as a safe and reliable jurisdiction,” is eroding? As with a handful of other things discussed in this report, I leave that to the reader to decide.

[1] I previously discussed at length the causes and consequences of the dollar’s loss of reserve currency status in IT’S THE END OF THE DOLLAR AS WE KNOW IT (DO WE FEEL FINE?), Amphora Report vol. 2 (May 2011), available here.

[2] Prior to the global financial crisis of 2008 the Fed purchased primarily US government bonds. However, it has since purchased a broad range of assets, including those that were part of the deal the Fed made with JP Morgan regarding its takeover of failing investment bank Bear Stearns.

[3] The Fed would be earning seignorage income directly rather than indirectly were it to purchase interest-bearing foreign securities instead of domestic ones. Note that the amount of seignorage income generated rises in proportion to the devaluation of the dollar relative to the currencies of US trading partners. That devaluation increases income is a simple accounting identity, although some Keynesians argue that this income is ‘real’. It is not. It is inflation.

[4] For a thorough discussion of the official BRIC position on these matters please see THE BUCK STOPS HERE: A BRIC WALL, Amphora Report vol. 3 (April 2012) available here.

[5] A recent article in the Turkish press detailing his comments on this topic can be found at the link here.

[6] For a discussion of the IMF’s recent reconsideration of some of their economic forecasting models, please see THE KEYNESIANS’ NEW CLOTHES, Amphora Report vol. 3 (2 November 2012). The link is here.

[9] For convenience purposes, smaller countries could always peg their currencies to that of a major trading partner and, in this way, indirectly back their currencies with gold.

This article was previously published in The Amphora Report, Vol 3, 27 November 2012.

Richard Cantillon is the key to a lot of this.

Sorry about that (big clumsy fingers).

Richard Cantillon is the key to a lot of this. At the end of a boom-bust event things are NOT what they would have been had the boom-bust had not happened.

It is NOT the case that there is a credit money boom, then the inevitable bust and “broad money” (bank credit) shinks back down towards the “monetary base” and everything returns to what it was. No – some people (normally wealthy and well connected people) are better off than they would otherwise have been (had no credit-money expansion happened) and a lot of other people are worse off than they would have been.

Overall the losses our greater than the gains – it is not a zero sum game, it is a negative sum game. The economy (the population) is worse off than it would have been (would have been had it been based on work and real savings – not a credit money bubble), but some people (a small but important minority) are better off than they would have been.

That is the key. Not the people who really believed in the fantasy that “money” could be lent out that no one really saved – but the people who knew the whole thing was a scam, but so organised their activity so that they (personally) would benefit from the scam.

Those are the sort of people who even after the scam has started to come apart will look you straight in the eyes and say “the money really existed and then the deflation destroyed it” and then they will pitch you their next scam (“to counter the deflation and restore the money supply”).

They are intelligent (some of the most intelligent people on the planet) and they know that just because you have conned someone previously does not mean you can not con them again. Shameless – but, sadly, it works.

Too harsh? No it is not too harsh – please observe how they are responding to the criminal behaviour of Central Banks in producing money (from nothing) and using it (directly or indirectly) to buy government (or sometimes even private) debt. They are celebrating this criminal behavour – and encouraging everyone to get back into the market (go buy shares and so on – they know that people who do such things are going to be wiped out in a few months).

“It is not criminal – because the government says it is legal, and a crime is just anything the government says is a crime and a legal thing is just whatever the government says is legal”.

Someone who comes out with that may call themselves a “Legal Positivist”, but actually they are just a crook. They may well make a lot of money – but they leave ruin and despair behind them.

It may be less difficult (due to the laws of the universe) to destroy than to create. But it is tragic that these people choose to use their intellegence (and their energy) to destroy rather than to create.

They could make money by creating (not destroying)- although, yes, it is harder (much harder), and slower (a lot slower), to make money that way.

“That said, there is no certainty that commodity prices are going to rise, but if they don’t, this is unlikely to be the direct result of government action. Indeed, a general decline in commodity prices would be an indication that governments are finally backing away from inflationary policies, something that would, eventually, set the stage for a sustainable economic recovery built on savings, rather than on debt.”

There is no way out for the Central Banks. You cannot have deflation with a fiat currency system, only disinflation.

If inflation rises, commodities (especially gold and silver) will rocket up in value.

If the Central Banks try and reverse now, the system will implode. A debt based monetary system is essentially a ponzi, where more units are needed to pay off the existing debts, that always rise faster than the ability to pay it off. When only the debt remains the system collapses, and the paper is worthless.

Government bonds are in a 200-300 year bubble. When the bubble pops, interest rates spike, the debt goes exponential, the system impodes, and the paper is worthless.

Commodities are 100% certain to increase in price. To have something tangible is better than to have nothing.

A country with a reserve currency is in exactly the same position as a bank. It can in effect hire out worthless bits paper.

So a country with a reserve currency ought to be able to make money out of that business. Unfortunately, the elite in such countries (politicians, central bank staff, etc) are normally too disorganised to run that “business” on a consistently profit making basis.

The way to make a profit is to arrange for inflation to slightly exceed the yield on the relevant government’s debt. That way those silly foreigners get a negative return (in real terms) on their investment. The US, Germany, UK and Japan have more or less done that in the last three years – but more by accident that design.

(As an aside, don’t you ever find it ironic that those who shout the loudest that gold is but a ‘barbarous relic’ are those who live and work atop the bullion vaults under the NY Fed or the Bank of England, for example?)

Yes, I bring it up all the time. The central banks’ hoarding of gold, and acceptance of the expense of protecting that element of limited use, is an obvious indication that ultimately even they don’t believe in fiat money.