“On October 15, the mark’s rate against the pound passed 18 milliards. On October 21, after the mark had moved in three days from 24 milliards to 80 milliards to the pound, Lord D’Abernon noted with some statistical glee that (at 60 milliards) this was ‘approximately equal to one mark for every second which has elapsed since the birth of Christ’. At the end of the month the banknote circulation amounted to 2,496,822,909,038,000,000 marks, and still everybody called for more.”

– From ‘When money dies: the nightmare of the Weimar hyperinflation’ by Adam Fergusson.

The internet has been nicely described by Lars Nelson of the New York Daily News as “a vanity press for the demented”.

Notwithstanding the bitter accuracy of this statement, we flit from time to time to sites like Twitter to attempt quixotically to redress the balance of popular opinion away from wrong-headed nonsense with regard to the financial world in favour of rational (perhaps even moral?) analysis. Last week we engaged in the following conversation:

Anonymized Tweeter: “are u a conspiracy theorist?”

Us: “No, I just believe in sound money and small government. And not in central bankers – who caused this depression too.”

AT: “we aren’t and never hv been in a depression. I’d also argue without current radical policy action from Bernanke we’d be MUCH worse off.”

Us: “If this ends in currency collapse, which I think it might, will we all be better off? Fed to blame in any case.”

AT: “Perhaps ud have preferred a much deeper recession / depression and full banking collapse Japanese style deflation over QE?”

Us: “I think I would rather have a nasty short term recession and bank nationalisations over a perma-depression.”

Admittedly, it’s not exactly War and Peace, but there you go.

The conventional reaction to the extraordinary economic and policy events of the last five years has been to accept an alphabet soup of trillions of dollars’ worth of taxpayer-funded inflationary monetary stimulus directed exclusively at banks as averting what would otherwise have been a nasty though perhaps relatively short-lived deflationary bust. As with the 1930s there is no counter-factual, so we will never know for sure. But we incline more towards Michael Lewis’s take on things. In this summary, our favourite brokerage firm and definitive non-bank Goldman Sachs can serve as the representative of broader banking interests:

Stop and think once more about what has just happened on Wall Street: its most admired firm conspired to flood the financial system with worthless securities, then set itself up to profit from betting against those very same securities, and in the bargain helped to precipitate a world historic financial crisis that cost millions of people their jobs and convulsed our political system. In other places, or at other times, the firm would be put out of business, and its leaders shamed and jailed and strung from lampposts. (I am not advocating the latter.)

Instead Goldman Sachs, like the other too-big-to-fail firms, has been handed tens of billions in government subsidies, on the theory that we cannot live without them. They were then permitted to pay politicians to prevent laws being passed to change their business, and bribe public officials (with the implicit promise of future employment) to neuter the laws that were passed — so that they might continue to behave in more or less the same way that brought ruin on us all.

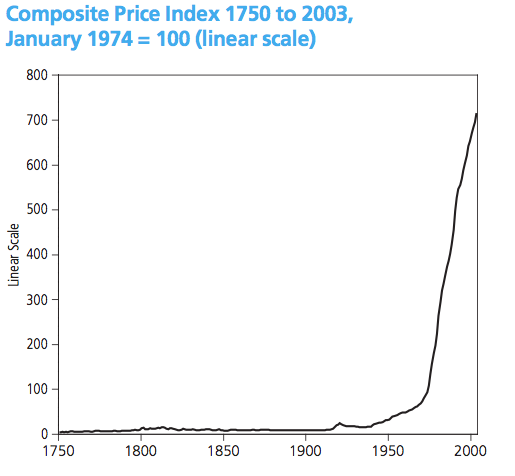

Like Michael Lewis, this commentator also once worked as a bond salesman – nobody’s perfect – so we claim a modest degree of informedness when it comes to the workings of the banking and investment banking business. So our take on things can perhaps best be summarised as follows. We are living through the tail end of a 40-year credit bubble that has reached the terminal phase of its expansion. As Herbert Stein rightly observed, if something cannot go on forever, it will stop. But bankers don’t want the music to stop, and they are perfectly willing to steal from taxpayers in order to pay the orchestra. Politicians cravenly obeying the unfit-for-purpose four- or five-year electoral cycle are now displaying the biggest tin ear in history to the ever-louder complaints of constituents of what remains of the real, productive economy as opposed to narrowly self-interested Big Finance.

The popular debate, if any, runs out of road once we start to discuss money itself – a critical component within the debate, but insufficiently understood by just about everybody. Why have the untold trillions of central bank ex nihilo base money not already triggered eye-watering levels of inflation? 1) Because they mostly sit inert (so far) as commercial bank reserves. 2) Because commercial banks’ balance sheets remain mostly upside down (i.e. the banks are still pretty much insolvent), so the last thing these firms are going to do is actually lend it out to anyone. 3) There is already uncomfortable inflationary leakage feeding into the prices of many financial assets, including the obvious usual suspects, stocks and bonds.

And so the economy, like that of Weimar Germany, remains moribund even as more and more money gets printed. At some point, which may be fast approaching, the marginal user of money is going to get fed up at this constant devaluation of their purchasing power, and the rush into hard assets will begin. As longstanding readers and our clients are well aware, we love hard assets. As one highly successful fund manager recently wrote to us, hard assets rock.

In the meantime, the financial media continue to prattle on about this mythical ‘Great Rotation’, whereby a polarised constituency of bond investors is mysteriously going to get religion and an overnight mandate change and pile into overpriced stocks instead. This theory is so absurd we won’t waste much more time on it. Suffice to say, if stocks are “attractive” primarily because of their valuation relative to bonds, their “attractiveness” breaks down when bond prices do, as they surely will at some point in the near to medium term. And bond prices are only where they are because of extraordinary monetary stimulus in the form of money which is being devalued on a daily basis. Did we mention hard assets?

Unfortunately, debate is useless because only politicians have sufficient clout to bang heads in the banking (and central banking) sector, and most politicians don’t appear to understand money creation (or destruction) either.

Back to Adam Fergusson:

What really broke Germany was the constant taking of the soft political option in respect of money. The take-off point therefore was not a financial but a moral one; and the political excuse was despicable, for no imaginable political circumstances could have been more unsuited to the imposition of a new financial order than those pertaining in November 1923, when inflation was no longer an option. The Rentenmark was itself hardly more than an expedient then, and could scarcely have been introduced successfully had not the mark lost its entire meaning. Stability came only when the abyss had been plumbed, when the credible mark could fall no more, when everything that four years of financial cowardice, wrong-headedness and mismanagement had been fashioned to avoid had in fact taken place, when the inconceivable had ineluctably arrived.

Money is no more than a medium of exchange. Only when it has a value acknowledged by more than one person can it be so used. The more general the acknowledgement, the more useful it is. Once no one acknowledged it, the Germans learnt, their paper money had no value or use – save for papering walls or making darts. The discovery which shattered their society was that the traditional repository of purchasing power had disappeared, and that there was no means left of measuring the worth of anything. For many, life became an obsessional search for Sachverte, things of ‘real’, constant value: Stinnes bought his factories, mines, newspapers. The meanest railway worker bought gewgaws. For most, degree of necessity became the sole criterion of value, the basis of everything from barter to behaviour. Man’s values became animal values. Contrary to any philosophic assumption, it was not a salutary experience.

What is precious is that which sustains life. When life is secure, society acknowledges the value of luxuries, those objects, materials, services or enjoyments, civilised or merely extravagant, without which life can proceed perfectly well but which make it much pleasanter notwithstanding. When life is insecure, or conditions are harsh, values change. Without warmth, without a roof, without adequate clothes, it may be difficult to sustain life for more than a few weeks. Without food, life can be shorter still. At the top of the scale, the most valuable commodities are perhaps water and, most precious of all, air, in whose absence life will last only a matter of minutes. For the destitute in Germany and Austria whose money had no exchange value left existence came very near these metaphysical conceptions. It had been so in the war. In All Quiet on the Western Front, Müller died ‘and bequeathed me his boots – the same that he once inherited from Kemmerick. I wear them, for they fit me quite well. After me Tjaden will get them: I have promised them to him.’

In war, boots; in flight, a place in a boat or a seat on a lorry may be the most vital thing in the world, more desirable than untold millions. In hyperinflation, a kilo of potatoes was worth, to some, more than the family silver; a side of pork more than the grand piano. A prostitute in the family was better than an infant corpse; theft was preferable to starvation; warmth was finer than honour, clothing more essential than democracy, food more needed than freedom.

We have been warned. And we have been here before. What really broke [Germany] was the constant taking of the soft political option in respect of money. Are our politicians, journalists and central bankers even listening? There are none so deaf as those who will not hear.

This article was previously published at The price of everything.

Why “bank nationalisations”?

If a bank goes bankrupt a bank goes bankrupt – it closes its doors and the people who intrusted money to it, lose that money.

If the government has a duty to step in (either with bailouts or with nationalisation) then banking is not really a private business at all, it is part of the government. And bankers should be on the minimum wage – or benefit level income.

As for Japan – its wild fiscal and monetary policies are very similar to those of Britain and the United States

Your suggestion on banker salaries is emotionally appealing but a pay scale based on civil service levels would seem to be both realistic and appropriate for relatively risk free employment.

Every credit-money boom in the United States (from 1819 to 1921) ended in a bust – but in very bust before 1929 the government allowed wages and prices to adjust (allowed markets to clear).

In 1929 the government of Herbert “The Forgotten Progressive” Hoover did not allow that. And the results of not allowing it were a mess.

There is the “counter factual”.

As for banks……

They should be a BUSINESS.

The business of lending out REAL SAVINGS.

If someone entrusts their savings to a bank (to be lent out) and the bank bankrupt then they should LOSE THEIR SAVINGS.

One can insure against fire, flood (and so on), but not against bad busines judgement.

Paul,

I agree with everything you wrote here except the last sentence:

“One can insure against fire, flood (and so on), but not against bad busines judgement.”

In fact, one can insure against anything that someone else is prepared to insure you against. This includes various forms of bad judgement (on the part of yourself and others).

What one can’t insure against is systemic failure that causes the insurers themselves to go bust.

Certain insurance policies are unlawful as against public policy, e.g. to insure against the consequences of committing crime, and therefore unenforceable. That apart, I doubt that anyone sells ‘bad business judgment’ insurance under whatever label, or that anyone would admit to buying it. “Come and insure your Betamax machines investment here.” “Can I insure myself against buying HMV because I think it is a money pit?”, as opposed to “Is this Algerian gas plant going to be a safe place?” and often insurers don’t cover war, insurrection, Acts of God etc.

There have been State-backed export credit guarantees, which is really re-inforcing failure by encouraging exports and then paying for them if the deal goes bad, reducing risk but with costs borne ultimately by taxpayers.

Herbert “The Forgotten Progressive” Hoover

Heh. Don’t you just love seeing Hoover described as the “arch-conservative” who did nothing while the country fell apart? Well, that’s their story and they’re sticking to it.

Mr Howard – the lies the left tell about the government increasing, taxation increasing, regulation crazy Herbert Hoover are astonishing.

The education system is a lie-fest of collectivist propaganda – which is exactly what one should expect (as H. Mann was inspired by Frederick the Great).

mrg – my apologies.

You (or anyone else) can, of course, use your own money to offer insurance against bad business judgement if you wish to do so.

My objection is to tax money (or Central Bank money) being used for this purpose.