Late last year, a group of institutional investors sent a letter to officials in Brussels, warning that European Union accounting standards are “destabilizing banks” and “damaging national economies.”

Accountancy may rhyme with geeky, but the investors were right and addressing the issue they highlighted is essential to restoring Europe’s financial health.

The European Commission officials were sufficiently worried by the U.K. investors’ charge — namely that because of EU accounting rules, banks may have systematically overstated their assets and distributed nonexistent profits as dividends and bonuses — that they said they would open an inquiry. Last week, the board that administers the rules put forward its own proposals. These are likely to perpetuate, not fix, the problem.

The rules concerned are called the International Financial Reporting Standards, and they’re used across the EU and in a growing number of other countries around the world. The potential misreporting involved is significant. In the case of just one U.K. bank, Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc, I and others calculated that IFRS rules resulted in the bank understating its 2011 losses by 19.5 billion pounds, or roughly twice the U.K. taxpayer bill for the 2012 Olympic Games.

Deceptive Flattery

If this is correct, then the state’s 45.5 billion-pound ($67.7 billion) bailout of RBS in 2008 and 2009 was calculated against a balance sheet that probably also flattered to deceive. The risk of such faulty numbers is clear: If RBS fails to recoup this hole in its accounts through genuine profits, then the U.K. taxpayer may be on the hook for about 20 billion pounds more than the government bargained for. Last week, RBS reported a larger than expected loss in 2012 of slightly less than 6 billion pounds.

Like the U.S. generally accepted accounting principles, better known as GAAP, Europe’s accounting standards are detailed guidelines for the presentation of financial information. Just as governments publish manuals on how to drive a car safely, so they have encouraged the production of accounting guidelines for financial reporting.

The legal impact of the guidelines differs widely in the two scenarios, however. Driver’s manuals are nothing more than that, manuals, which no court would substitute for the law. If a driver starts to brake at the correct distance from a stop sign, but still fails to stop, it is no defense to have followed the manual — he or she broke the law. Under European accounting law, following IFRS standards is a defense and the guidelines have been allowed to override national laws.

The rule that concerns investors the most restricts provisioning against expected future loan losses. Under IFRS, loss provisions can only be booked (thus reducing this year’s profits) if a loan event, such as a default, has occurred. The U.S. rule makers who oversee GAAP have refused to follow the IFRS in this. Talks aimed at converging U.S. and EU expected- loan-loss accounting rules ended without result last July.

It is misleading to shareholders and dangerous for the banking system if commercial banks can declare a profit when they expect a loss, as it perversely incentivizes bank executives to wreck their banks. This is because bank executives tend to prioritize short-term risks and rewards: If they know that any negative outcome of a loan decision can be parked in the blue yonder, delaying ill effects on the bank’s performance and bonus pool, they will be more likely to ignore the risks and make the deal.

Prudent Accounting

U.K. law deals with this issue in sections of the Companies Act, called the capital maintenance rules, which require that directors prepare “true and fair” accounts, guided by the conservative principle of “prudence.” This approach means that banks should report the value of each loan at the lower of either its original cost or current market value. Because of IFRS, however, this part of the Companies Act isn’t enforced.

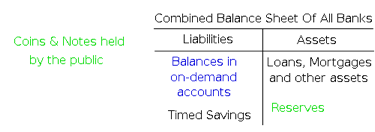

Equally dangerous is the effect on regulators. Working with accounts that underreport losses damages their ability to accurately assess the capital adequacy and stability of banks’ balance sheets.

Steve Baker, who in 2011 submitted draft legislation to Parliament to repeal the IFRS rules, puts the problem succinctly:

IFRS create a death spiral. Banks silently destroy their capital under the guise of profit, then they require taxpayer support, then the process starts again.

Defenders of IFRS say that these rules promote neutrality and objectivity — after all, if you estimate future losses for reporting purposes, why not future profits, too? They say the rules were changed to prevent “smoothing,” in which companies would time the recognition of income in order to create an artificially steady stream of profits. But surely smoothed profit streams cost shareholders and, in the case of a bailed- out bank, taxpayers less than exaggerated ones? Besides, profit smoothing was always illegal so long as laws were enforced.

What really changed in 2005, when the U.K. amended its laws to give banks the option to prepare accounts under IFRS rules, was that underprovisioning for losses became compulsory.

The evidence that revealed RBS’s Olympic-scale overvaluation came from the accounts of the U.K.’s bad-bank insurer, for which IFRS has different accounting rules. Unlike banks, insurers are required to value their assets and liabilities, taking into account probable future losses. This reporting difference highlighted the almost 20 billion-pound discrepancy in RBS’s 2011 accounts that the two sets of accounting rules produced.

Scrutiny Needed

Let’s hope that the European Commission will scrutinize the IFRS standards closely — it won’t be easy. The International Accounting Standards Board, which drew up the rules, doesn’t appear to accept the gravity of the problem. At a meeting last year, I explained to three senior board officials why profits calculated under the current rules aren’t safe for distribution. The officials acknowledged the problem, saying that banks should maintain two profit calculations, one for reporting to shareholders, and the other — not following IFRS rules — to determine distributions to shareholders. Surely this is false accounting?

Now the IASB has proposed a fix for the problem, recognizing that the delayed recognition of expected losses has proved “a weakness” during the financial crisis. Yet their proposed solution is to add more micro-rules that define the specific situations in which banks should be allowed to declare an impairment and book losses.

This approach is fundamentally wrong. The IFRS rules are the problem, because they interfere with enforcement of the law. Banks should decide when to provision for a loss, and the full force of the Companies Act should be used to punish them if they do so dishonestly. More detailed standards will just encourage more manipulation of them.

This article was previously published at Bloomberg.com.