On Thursday April 4 the Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Janet Yellen said in Washington the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) should be prepared to alter its $85 billion monthly pace of bond buying based on changes in the economic outlook.

Yellen’s comments support a proposal by St. Louis Fed President James Bullard to reduce the pace of purchases as the economy improves, or expand it if the economy weakens.

Also, the Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said last month the FOMC is considering this strategy to “appropriately calibrate” its policy.

The view that the Fed should calibrate its monetary policy in line with the likely state of the economy stems from the popular way of thinking that the role of the central bank is to make sure that the economy stays on a path of balanced economic growth.

According to this way of thinking the economy is seen as some kind of space ship that has deviated from its trajectory.

To bring it back onto the correct path, policy makers must give it an external push. So if the push in terms of loose monetary policy doesn’t produce the required results then policy makers must become more aggressive until the space ship is brought onto the desired path.

Conversely, if the economy, for whatever reason, is pushed onto the path of high inflation, then the central bank by means of a tighter monetary stance must bring the space ship onto the “correct” path.

Within this way of thinking, given that the economy is currently way below its right growth path there are plentiful of unemployed resources. Consequently, this permits policy makers to adopt a very aggressive loose stance without igniting inflation.

We suggest that this way of thinking is erroneous. An economy is about human beings and not about a space ship that follows along a growth path.

A policy that attempts to bring the economy onto the “correct” trajectory leads to a diversion of wealth from wealth generators to non–wealth-generating activities, thereby weakening the process of the wealth generation, i.e. it leads to an economic impoverishment.

In the meantime, the latest economic data seems to support the view that the Fed is unlikely to reverse its loose monetary stance soon.

The ISM manufacturing activity index fell to 51.3 in March from 54.2 in the previous month – whilst the ISM services index eased to 54.4 last month from 56 in the month before.

Non farm employment increased in March by 88,000 against the median forecast of economists for an increase of 190,000. Year-on-year employment increased by 1.91 million after rising by 2.027 million in February and an increase by 2.03 million in January. Additionally the diffusion index of employment in the private sector fell to 54.3 last month from 59.6 in February and 65.2 in December last year.

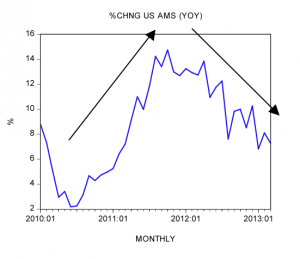

Elsewhere we have suggested that fluctuations in economic data are set in motion by fluctuations in the growth momentum of money supply as depicted by our monetary measure AMS.

After closing at 2.2% in June 2010 the yearly rate of growth of AMS climbed to 14.8% by October 2011.

Afterwards the yearly rate of growth has been following a declining path closing at 7.3% in March this year. (A change in the money supply rate of growth doesn’t affect all activities instantly – there is a time lag. For some activities the time lag is short while for others it is much longer).

We suggest that the fact that the growth momentum of AMS has been declining since October 2011 implies that downward pressure on economic activity has already been set in motion.

As time goes by the supporting effect on economic activity from the rising growth momentum of AMS during June 2010 to October 2011 is likely to weaken whilst the fall in growth momentum since October 2011 onward is likely to start to dominate the economic scene.

Based on the lagged growth momentum of real AMS (AMS adjusted for CPI) we suggest that the growth momentum of industrial production could come under strong pressure from the second half of this year. This is likely to undermine the growth momentum of employment (see chart).

We hold that massive monetary pumping by the Fed not only didn’t provide support to the economy but on the contrary has severely damaged the process of wealth generation. Elsewhere we have shown that it is the formation of real wealth that funds and thereby supports underlying economic growth.

This runs contrary to the popular way of thinking that loose monetary policy can somehow fund and grow an economy. All that loose monetary policy can do is to give rise to various non-productive bubble activities and thereby undermine underlying economic growth.

As long as the pool of real wealth is expanding loose monetary policies can give the impression that they grow the economy. Once however the pool becomes stagnant, or starts to decline, the economy follows suit.

In this case if central bank policy makers try to enforce aggressive monetary pumping this weakens the wealth generation process and weakens the pool of funding further. There are signs that this might be already happening. As a rule when the central bank pushes money into the banking system banks lend this money out thus boosting the money supply rate of growth and after a time lag this boosts the economic activity.

At present this mechanism is not working. Despite a massive increase in the Fed’s pumping as depicted by its balance sheet, banks so far have chosen to sit on the pumped cash rather than lend it out. In early April the Fed’s balance sheet stood at $3.2 trillion against $0.9 trillion in January 2008. Banks surplus cash jumped to $1.726 trillion in early April from $1.578 trillion in January. In January 2008 surplus cash stood at around $2.4 billion.

As the pool of real wealth comes under pressure banks find it much harder to acquire good quality borrowers, hence the supply of lending is slowing down. Now if the Fed were to attempt to force banks to increase lending this is not going to help real economic growth if the pool of funding is under pressure. The best thing the Fed could do to help the economy is to do nothing as soon as possible. This will strengthen wealth generators and in turn the wealth generation process.

Summary and conclusion

Some Fed officials have suggested that once the US economy gains strength it will be appropriate to reduce monetary pumping. The latest economic data seems to support the view that the US central bank is unlikely to reverse its loose monetary stance soon. The ISM manufacturing and services indexes have weakened last month whilst employment increased in March well below economists’ expectations. We suggest that the fact that the growth momentum of AMS has been declining since October 2011 implies that downward pressure on economic activity has already been set in motion. We also hold that the process of wealth generation was badly damaged by loose monetary policies of the Fed. This runs the risk of a prolonged economic slump. The best thing the Fed could do to help the economy is to do as soon as possible nothing.