In his New York Times article of May 7, columnist Bruce Bartlett laments that given the current state of economic affairs we need more Keynesian medicine to fix the US economy. According to Bartlett the core insight of Keynesian economics is that there are very special economic circumstances in which the general rules of economics don’t apply and are in fact counterproductive. This happens when interest rates and inflation rate are so low that monetary policy becomes impotent; an increase in the money supply has no boosting effect because it does not lead to additional spending by consumers or businesses. Keynes called this situation a “liquidity trap”. Keynes wrote,

There is the possibility, for the reasons discussed above, that, after the rate of interest has fallen to a certain level, liquidity-preference may become virtually absolute in the sense that almost everyone prefers cash to holding a debt which yields so low a rate of interest. In this event the monetary authority would have lost effective control over the rate of interest [1]

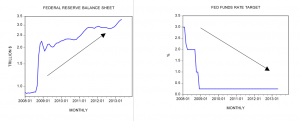

Bartlett holds that under such circumstances government spending can be highly stimulative because it causes money that is sitting idle in bank reserves or savings accounts to circulate and become mobilized through consumption or investment. Thus monetary policy becomes effective once again. Bartlett regards this as an extremely important insight that policy makers have yet to grasp. According to our columnist, despite massive monetary pumping by the Fed since 2008, it has produced very little boosting effect on the economy. The Fed’s balance sheet jumped from $0.897 trillion in January 2008 to $3.3trillion in early May 2013. The Federal Funds

Rate target stood at 0.25% in early May against 3% in January 2008.

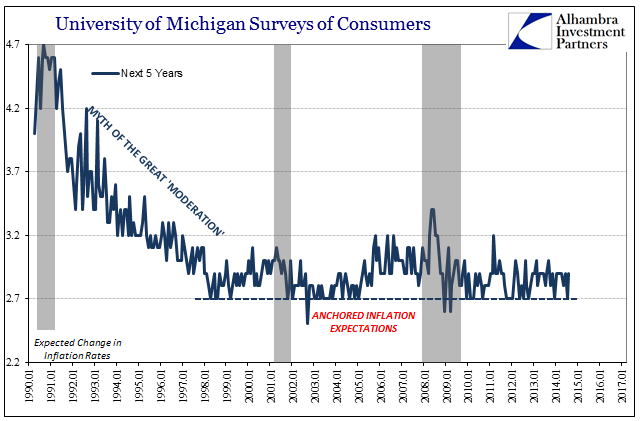

According to Bartlett, in normal times one would expect such an increase in money pumping to be highly inflationary and sharply raise market interest rates. That this has not happened says Bartlett, is a proof that we have been in a liquidity trap for several years. Bartlett concludes that we needed a lot more government spending than we got to get the economy out of its doldrums. Note also that Nobel Laureate in economics Paul Krugman holds similar views. For them what is needed is a re-activation of the monetary flow that for some unknown reasons got stockpiled in the banking system. Observe that in the Keynesian framework the ever-expanding monetary flow is the key to economic prosperity. What drives economic growth is monetary expenditure.

Why is money not the driver of economic growth?

Contrary to popular thinking monetary flow has nothing to do with an economic growth as such. Money is simply a medium of exchange and nothing more than that. Also, note that people don’t pay with money but rather with the goods and services that they have produced.

For instance, a baker pays for shoes by means of the bread he produced, while the shoemaker pays for the bread by means of the shoes he made. When the baker exchanges his money for shoes, he has already paid for the shoes, so to speak, with the bread that he produced prior to this exchange. Again, money is just employed to exchange goods and services. Being the medium of exchange, money can only assist in exchanging the goods of one producer for the goods of another producer.

What drives the economic growth is savings that are used to fund the increase and the enhancement of tools and machinery i.e. capital goods or the infra-structure that permits the increase in final goods and services i.e. real wealth to support people’s lives and well beings.

Contrary to popular thinking, an increase in the monetary flow is in fact detrimental to economic growth since it sets in motion an exchange of something for nothing – it leads to the diversion of real wealth from wealth generators to wealth consumers. This in the process reduces the amount of wealth at the disposal of wealth generators thereby diminishing their ability to enhance and maintain the infrastructure. This in turn undermines the ability to grow the economy.

What is behind the so called liquidity trap?

The fact that so far the Fed’s massive pumping has not resulted in a massive monetary flood should be regarded as good news. Imagine that if all that pumping were to enter the economy it would have entirely decimated the machinery of wealth generation and produced massive economic impoverishment. It seems that market forces have so far managed to withstand the onslaught by the US central bank. What allowed this resistance is not some kind of ideology against aggressive pumping by the Fed (in fact most experts and commentators are of the view that the Fed should push a lot of money in difficult times) but the fact that the process of real wealth generation has been severely damaged by the previous loose monetary policies of Greenspan’s and Bernanke’s Fed.

The badly damaged process of wealth generation has severely impaired true economic growth, and obviously this has severely reduced the number of good quality borrowers and so has reduced banks’ willingness to lend. Remember that in essence banks lend real wealth by means of money. They are just intermediaries. Obviously, then, if wealth formation is getting impaired, less lending can be done. We suggest that it is this fact alone that explains why all the pumping by the Fed has ended up stacked in the banking system. So far in early May banks have been sitting on over $1.7 trillion in surplus cash. In January 2008 surplus cash stood at $2.4 billion.

Given the high likelihood that the process of real wealth generation has been severely damaged this means that the pace of wealth generation must follow suit. Now, contrary to popular thinking an increase in government spending cannot revive the process of wealth generation, but on the contrary it can only make things much worse. Remember: government is not a wealth generating entity so in this sense increases in government spending generate the same damaging effect as monetary printing does (it leads to the diversion of wealth from wealth generators to wealth consumers). Observe that in 2012 US Government outlays stood at $3.538 trillion, an increase of 98% from 2000.

As long as the rate of growth of the pool of real wealth stays positive, this can continue to sustain productive and nonproductive activities.

Trouble erupts, however, when, on account of loose monetary and fiscal policies, a structure of production emerges that ties up much more wealth than the amount it releases.

This excessive consumption relative to the production of wealth leads to a decline in the pool of wealth.

This in turn weakens the support for economic activities, resulting in the economy plunging into a slump. (The shrinking pool of real wealth exposes the commonly accepted fallacy that loose monetary and fiscal policies can grow the economy.)

Needless to say, once the economy falls into a recession because of a falling pool of real wealth, any government or central-bank attempts to revive the economy must fail.

This means that a policy such as lifting government outlays to counter the liquidity trap will make things much worse.

Not only will these attempts not revive the economy; they will deplete the pool of real wealth further, thereby prolonging the economic slump.

Likewise any policy that forces banks to expand lending “out of thin air” will further damage the pool and will further reduce banks’ ability to lend.

Again the foundation of lending is real wealth and not money as such. It is real wealth that imposes restrictions on banks’ ability to lend. (Money is just the medium of exchange, which facilitates the flow of real wealth.)

Note that without an expanding pool of real wealth any expansion of bank lending is going to lift banks’ nonperforming assets.

Summary and conclusion

Contrary to various experts we suggest that in the current economic climate an increase in government outlays is not going to make Fed’s loose monetary policies more effective as far as boosting economic activity is concerned.

On the contrary, it will weaken the process of wealth generation and will retard economic growth.

What is needed to get the economy going is to close all loopholes for money creation and drastically curtail government outlays.

This will leave a greater amount of wealth in the hands of wealth generators and will boost their ability to grow the economy.

[1] John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, MacMillan & Co. Ltd. (1964), p. 207.

What economic doldrums? All stock market indices show that business is more profitable than ever. The only fly in the ointment is higher than normal unemployment, which leads to grumbling by the plebs. Central bank strategy of flooding the world with fiat currency is part of an attempt to fix interest rates, which, like fixing the price of any commodity, is destined to create market distortions. The housing bubble was the trigger that sent Spanish carpenters home and Irish carpet layers commiserating in the pub on rainy afternoons. Zero interest rates don’t seem to have affected the situation much.

I’m sure we’re all deeply grateful to Frank Shostak for his amazing insight to the effect that better or larger quantities of capital equipment promote economic growth. I’d guess the average fifteen year old has worked that out.

However, the problem addressed by Keynes was: what to do when consumers just aren’t minded to purchase goods and services in sufficient quantities to keep the workforce fully employed. That problem occurs when consumers save money instead of spend it (Keynes “paradox of thrift”).

The solution: supply consumers with more money. They’ll then go out and buy goods and services. And contrary to Shostak’s suggestions, there is no “wealth destruction” involved as long as those supplying those goods and services charge enough to pay for replacement of capital equipment. And I see no reason to suppose they won’t.

Of course there is a blindingly obvious potential problem with the above money creation policy, namely that sometime down the road the increased quantity of money might give rise to EXCESS spending and cause excess inflation. In that case government just has to raise taxes (and/or cut public spending) and withdraw money from the private sector. No government will ever get that high wire act right. But a bit of stimulus in a recession is better than doing nothing.

Re Chuck Martel’s point about interest rate adjustments, I agree with him. I.e. I favour stimulus in a recession, but not in the form of interest rate cuts.

what to do when consumers just aren’t minded to purchase goods and services in sufficient quantities to keep the workforce fully employed

I suppose even fifteen year old boys could also figure out that if consumers are in a mood to save that all is not lost. Entrepreneurs will then borrow those saved funds to invest in capital improvements that will improve the profitability of slower-growing consumer goods spending.

Mr. Keynes and, apparently, you miss the point that supplying consumers with more money will only result in the same amount of consumer goods being sold at a higher price. Sure, GDP increases [through the magic of government statisticians], but nothing really changes.

If entrepreneurs automatically borrowed and spent whatever consumers and others saved, there wouldn’t be a problem. But that’s exactly what DOESN’T HAPPEN. Corporations are sitting on record high cash piles at the moment, plus banks aren’t doing much lending at the moment: they’re hoarding much of what is deposited with them so as to get their balance sheets back into shape.

As to the idea that “supplying consumers with more money” automatically results in price rises, that’s not true either. If consumers are in cautious or subdued mode, as they are at the moment, they just don’t spend a significant proportion of any new money, so there is no effect on prices. David Hume pointed out 250 years ago in his essay “Of Money” that if people don’t do anything with a money supply increase, nothing happens to prices. His actual words were, “If the coin be locked up in chests, it is the same thing with regard to prices, as if it were annihilated.”

It is always in a governments interest to maintain the bubble fully blown however, when people stop spending it is almost certainly and always the most sensible thing to do and when governments decide to provide a counterbalance it is almost always certainly the most stupid thing to be doing.

Bad investments that cannot be sustained other than in a bubble of excessive credit must be allowed to liquidate in order that the economy is allowed to rebalance.

The Keynes solutions do not make any sense to anybody with an iota of common sense.

I see – so according to Bruce B. in the New York Times the United States needs even MORE government spending (on top of the record levels it already has).

These people are mad – stark, staring bonkers.

Whether it is the Cambridge “left” or the Peronist “right” (I see BNP Ralph is here again)they have not got a clue.

Indeed I doubt the distinction between the Cambridge left and the Peronist right is realy worth making. In many ways they are one and the same.

After all General Peron was an ardent Keynesian (he just cut private banks out of the loop and did everything via the government) and Keynes himself praised the totalitarian economic management of Nazi Germany in the introduction to the German edition of his “General Theory”.

I await the comming of some idiot who is going to say “print and spend works in Japan”.

It did not work in 1920s Japan (the refusal to allow a bust in 1921 – led to a breakdown in 1927 two years before the Wall Street Crash), contrary to the international establishment (including Conservative party supporting outlets such as the British Spectator magazine) it did NOT work in 1930s Japan, and it has not worked over the last two decades either.

Spot on article. Another title could have been “its the production stupid”. For British readers, during the Clinton/Bush-the-elder campaign, the slogan of the Clinton campaign was “its the economy stupid”.

Hyperinflation exploded in Germany when the Belgian and French troops occupied the German industrial sector to take their reparations out directly from German industrial production. The German factory and mine workers walked out in protest. Fearing increased unrest, the German government accelerated the printing of money to pay the workers even though they still had not gone back to work. So a big chunk of PRODUCTION stopped, but the money did not. That’s when hyperinflation exploded.

Money creation is always inflationary and not a good thing, but if production continues or increases, its effect is greatly lessened. But when you get both a reduction in production and increase in money supply, look out.

Great article. We are taught as a first principle that money is a medium of exchange…and then it seems we forget.

Money is the servant of production and not its master. Print whatever you like but you will not cause increased production because the new money is no more than transitory and whilst it may well blow up a few bubbles they are not a permanent feature and will soon disappear.

Because of its transitory nature the new money cannot remain as an increase real in the money supply for long enough to stimulate an increase in production although it may well remain long enough to result in an increase in imports.