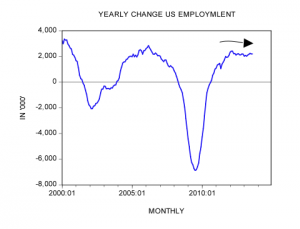

On September 17-18 US central bank policy makers are likely to decide on the reduction in their monthly purchases of bonds by between $10 billion to $15 billion. A major determining factor on the size of the reduction is going to be set by their view regarding improvements in the labour market. On this the yearly change in employment stood at 2.2 million in August against the same figure in the month before.

Most experts are of the view that given the still subdued growth momentum of employment Fed policy makers are likely to announce that the US central bank is going to keep its near zero interest rate policy for a prolonged period of time. This, it is held, should prevent negative side effects coming from the reduction in bond purchases.

For instance, in 1994 when the Fed started a tightening cycle the federal funds rate rose from 3.05% in January 1994 to 6.04% in April 1995. This, it is held, caused a sharp fall in the pace of economic activity. The yearly rate of growth of industrial production fell from 7% in December 1994 to 2.7% by December 1995.

We suggest that it is changes in money supply rather than changes in interest rates that drive economic activity as such. Interest rates are just an indicator as it were.

A fall in the growth momentum of industrial production during December 1994 to December 1995 occurred on account of a sharp decline in the yearly rate of growth of AMS from 13.7% in September 1992 to minus 0.3% in April 1995.

This sharp fall in the growth momentum of AMS has weakened the support for various bubble activities that sprang up on the back of the previous rising growth momentum of AMS.

(Now even if the Fed would have kept the fed funds rate at a very low level what would have dictated the pace of economic activity is the growth momentum of AMS).

Note that a fall in the growth momentum of AMS was in line with the fall in the growth momentum of the Fed’s balance sheet – the yearly rate of growth of the balance sheet fell from 12.7% in June 1993 to 4.4% by December 1995.

What ultimately limits the pace of growth of AMS is the growth momentum of bank inflationary lending. The yearly rate of growth of inflationary bank lending fell from 23.3% in September 1992 to minus 0.7% by July 1995 – note that a fall in the growth momentum of the Fed’s balance sheet during June 1993 to December 1995 exacerbated the decline then in the growth momentum of banks inflationary lending.

Contrary to the 1993 to 1995 period, this time around the Fed’s monetary pumping as depicted by the growth momentum of its balance sheet has been ineffective in boosting the growth momentum of money supply given the banks reluctance to aggressively expand lending. (Bank’s lending growth at present doesn’t respond to changes in the Fed’s balance sheet).

The yearly rate of growth of the Fed’s balance sheet stood at 29.8% so far in September versus minus 1.4% in September last year.

Despite this pumping banks have chosen to accumulate cash rather than lending it out and are sitting on $2.1 trillion in cash. Given banks reluctance to aggressively expand lending the yearly rate of growth of AMS fell from 14.8% in October 2011 to 7.7% by August 2013.

We suggest that it is this fall in the growth momentum of AMS that will dictate the future pace of economic activity regardless of what the Fed is going to do.

(Note that the effect of changes in money supply on economic activity works with a time lag. It takes time for changes in money supply to diffuse its effect on the various parts of the economy).

We need to add to all of this the possibility that the pool of real wealth might be currently in difficulties on account of the Fed’s reckless policies.

(The near zero interest rate policy has caused a severe misallocation of scarce real savings – it has weakened the wealth generation process and thus the economy’s ability to support stronger real economic growth).

If our assessment is valid on this, we can suggest that a stagnant or declining pool of real wealth is likely to put more pressure on banks’ lending. Remember that it is the state of the pool of real wealth that dictates banks ability to lend without going belly up.

We can conclude that regardless of changes in the Fed’s balance sheet it is a fall in the growth momentum of AMS since October 2011 that will determine the pace of economic activity irrespective of the planned actions by the Fed. Given the possibility that the pool of real wealth might be in trouble this could put further pressure on the growth momentum of bank lending and thus the growth momentum of money supply.

Totally agree that it is the ‘supply’ of money and not the cost of money that determines the level of economic activity and therefrom wage and employment levels that matter to real people.

But I feel the following statement continues to dis-inform people about the nature of CB activities in a debt(paper) based system f money.

“Despite this pumping banks have chosen to accumulate cash rather than lending it out and are sitting on $2.1 trillion in cash.”

That a misleading use of the term ‘cash’.

There isn’t $2.1 Trillion in cash in existence that anyone knows of – and since a good portion of existing cash is in our pockets, the banks cannot be holding case.

Again, in a debt(paper) based system of money, all the reserves used by the central bank to balance deposit accounts and provide for payments, are considered to be – for CB-DI interaction purposes ONLY – cash equivalents.

Since there is an ‘owning’ cost for real cash in the money system, and an owning premium paid on all reserves in the system, had banks $2.1 Trillion in ‘cash’, there would be policy-based incentive for the banks to lend that cash out.

With $2.1 Trillion in reserves, the policy incentive is reversed.

The solution does not lie in policy, but in structural, institutional reform that ends the debt(paper) based system of money.

Thanks.

Seems the Fed don’t agree with this anymore

http://www.europac.net/commentaries/markets_focused_wrong_target

Perhaps all monetary stimulae is simply a question of causing a measure of temporary growth at one end of the spectrum whilst causing an equal contraction at the other end a little later on.

There is no such thing as a free lunch and this applys to increasing the fiat medium of exchange in the hope of increasing sustained production.