According to the popular way of thinking, bubbles are an important cause of economic recessions. The main question posed by experts is how one knows when a bubble is forming. It is held that if the central bankers knew the answer to this question they might be able to prevent bubble formations and thus prevent recessions.

On this, at the World Economic Forum in Davos Switzerland on January 27, 2010, Nobel Laureate in Economics Robert Shiller argued that bubbles could be diagnosed using the same methodology psychologists use to diagnose mental illness. Shiller is of the view that a bubble is a form of psychological malfunction. Hence the solution could be to prepare a checklist similar to what psychologists do to determine if someone is suffering from, say, depression. The key identifying points of a typical bubble according to Shiller, are,

- Sharp increase in the price of an asset.

- Great public excitement about these price increases.

- An accompanying media frenzy.

- Stories of people earning a lot of money, causing envy among people who aren’t.

- Growing interest in the asset class among the general public.

- New era “theories” to justify unprecedented price increases.

- A decline in lending standards.

What Shiller outlines here are various factors that he holds are observed during the formation of bubbles. To describe a thing is, however, not always sufficient to understand the key factors that caused its emergence. In order to understand the causes one needs to establish a proper definition of the object in question. The purpose of a definition is to present the essence, the distinguishing characteristic of the object we are trying to identify. A definition is meant to tell us what the fundamentals or the origins of a particular entity are. On this, the seven points outlined by Shiller tell us nothing about the origins of a typical bubble. They tell us nothing as to why bubbles are bad for economic growth. All that these points do is to provide a possible description of a bubble. To describe an event, however, is not the same thing as to explain it. Without an understanding of the causes of an event it is not possible to counter its emergence.

Defining bubbles

Now if a price of an asset is the amount of money paid for the asset it follows that for a given amount of a given asset an increase in the price can only come about as a result of an increase in the flow of money to this asset.

The greater the expansion of money is, the higher the increase in the price of an asset is going to be, all other things being equal. We can also say that the greater the expansion of the monetary balloon is, the higher the prices of assets are going to be, all other things being equal. The emergence of a bubble or a monetary balloon need not be always associated with rising prices – for instance if the rate of growth of goods corresponds to the rate of growth of money supply no change in prices will take place.

We suggest that what matters is not whether the emergence of a bubble is associated with price rises but rather with the fact that the emergence of a bubble gives rise to non-productive activities that divert real wealth from wealth generators. The expansion of the money supply, or the monetary balloon, in similarity to a counterfeiter, enables the diversion of real wealth from wealth generating activities to non productive activities.

As the monetary pumping strengthens, the pace of the diversion follows suit. We label various non-productive activities that emerge on the back of the expanding monetary balloon as bubble activities – they were formed by the monetary bubble. Also note that these activities cannot exist without the expansion of money supply that diverts to them real wealth from wealth generating activities.

From this we can infer that the subject matter of bubbles is the expansion of money supply. The key outcome of this expansion is the emergence of non wealth generating activities.

It follows that a bubble is not about strong asset price increases but about the expansion of money supply. In fact, as we have seen, bubbles – i.e. an increase in money supply – can take place without a corresponding increase in prices. Once we have established that an expansion in money supply is what bubbles are all about, we can further infer that the key damage that bubbles generate is by setting non-productive activities, which we have labelled as bubble activities. Furthermore, once it is established that formation of bubbles is about the expansion in money supply, obviously it is the central bank and the fractional reserve banking that are responsible for the formation of bubbles. As a rule, it is the central bank’s monetary pumping that sets in motion an expansion in the monetary balloon.

Hence to prevent the emergence of bubbles one needs to arrest the monetary pumping by the central bank and to curtail the commercial banks’ ability to engage in fractional reserve banking – i.e. in lending out of “thin air”. Once the pace of monetary expansion slows down in response to a tighter central bank stance or in response to commercial banks slowing down on the expansion of lending out of “thin air” this sets in motion the bursting of the bubbles. Remember that a bubble activity cannot fund itself independently of the monetary expansion that diverts to them real wealth from wealth generating activities. (Again bubble activities are non-wealth generating activities).

The so-called economic recession associated with the burst of bubble activities is in fact good news for wealth generators since now more wealth is left at their disposal. (An economic bust, which weakens bubble activities, lays the foundation for a genuine economic growth). Note again that it is the expansion in the monetary balloon that gives rise to bubble activities and not a psychological disposition of individuals in the market place.

Psychology and economics

Psychology was smuggled into economics on the grounds that economics and psychology are inter-related disciplines. However, there is a distinct difference between economics and psychology. Psychology deals with the content of ends. Economics, however, starts with the premise that people are pursuing purposeful conduct. It doesn’t deal with the particular content of various ends.

According to Rothbard,

A man’s ends may be “egoistic” or “altruistic”, “refined” or “vulgar”. They may emphasize the enjoyment of “material goods” and comforts, or they may stress the ascetic life. Economics is not concerned with their content, and its laws apply regardless of the nature of these ends.[1]

Whereas,

Psychology and ethics deal with the content of human ends; they ask, why does the man choose such and such ends, or what ends should men value?[2]

Therefore, economics deals with any given end and with the formal implications of the fact that men have ends and utilize means to attain these ends. Consequently, economics is a separate discipline from psychology. By introducing psychology into economics one obliterates the generality of the theory, and renders it useless. The use of psychology is counterproductive as far as economic analyses are concerned.

Summary and conclusions

Contrary to Shiller, in order to establish that a bubble is forming we don’t need to apply the same methodology employed by psychologists. What we require is the establishment of a correct definition of what bubbles are all about. Once it is done, one discovers that bubbles have nothing to do with some kind psychological malfunction of individuals – they are the result of loose monetary policies of the central bank.

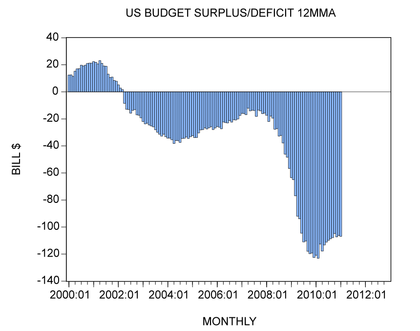

Furthermore, once we observe an increase in the rate of growth of money supply we can confidently say that this sets the platform for bubble activities – for an economic boom.

Conversely, once we observe a decline in the rate of growth of money supply we can confidently say that this lays the foundations for the burst of bubble activities – an economic bust.

You are quite right in pointing out the difference between description and cause in phenomena (bubbles) relating to the economy. Looked at in a slightly different way, the description of a bubble (as illustrated by the list of bubble characteristics listed by Shiller) can be thought of as symptoms of an underlying malady of a complex system.

Looked at in this way, it becomes apparent that the expansion of the money supply might also be a symptom rather than a cause. Therefore, it might be fruitful to consider the causes of monetary expansion. Might I suggest this may have something to do with the expanding role of the state? Isn’t it here where so much of the wealth creating activity is being diverted?

Rather than considering psychological approaches to understanding bubbles, wouldn’t it be more appropriate to view the state in terms of a mis-functioning of a complex system – much the same as a cancer is a mis-functioning element of the complex system of the human body?

It is quite true that a credit bubble (i.e. loans that are not from REAL SAVINGS) can be created without a Central Bank.

However, Central Banks do NOT (as is so often claimed) limit the folly of private banks – on the contrary they expand the folly (the credit bubble – the loans that do not come from REAL SAVINGS) to a level vastly greater than private banks would on their own.

Dr. Shostak,

As a devotee of your writing, I know you know the difference between money and currency and warehouse receipts. I see you are using the common definition of money, but let me test with a re-write:

“Now if a price of an asset is the amount of fiat currency paid for the asset it follows that for a given amount of a given asset an increase in the price denominated in fiat currency can only come about as a result of an increase in the flow of fiat currency to this asset.”

Now I think my re-write is technically correct, plus it avoids the confusion as to whether it is even possible inflation could happen if we actually used money, properly defined.

And I realize the rewrite, if correct, becomes esoteric. But the loose use of the term “money” makes progress unlikely since debaters are talking past each other, given profoundly different definitions of the term.

Might you school a devotee on this point, as to whether we should abide by strict definitions?

John Spiers

“Now if a price of an asset is the amount of fiat currency paid for the asset it follows that for a given amount of a given asset an increase in the price denominated in fiat currency can only come about as a result of an increase in the flow of fiat currency to this asset.”

I am certainly not Dr. Shostak, but for the purposes of this discussion, I think that a distinction without merit. The origin of money matters not if it can all be spent on the same stuff.

Hey Craig,

There is the problem. In the 1960s one could buy a gallon of gas with 2 dimes (which were silver at the time). Today a gallon is like $3.50 in fiat currency notes. You can still get a gallon of gas for 2 silver dimes, if you convert the dimes to fiat currency at a coin dealer. Silver dimes today bought what they did 50 years ago, but fiat currency does not.

Yes, money, no matter the origin, can be spent on the same stuff, but fiat currency is not money. Every fiat currency in history has failed, without exception. The dollar and pound will too. When it does, it can be spent on nothing, let alone the same stuff.

When the system goes down, who can articulate repair if unsecured derivatives, fiat currency, thin-air credit, asset backed credit, and who knows what is all called “money?” (And gold and silver deemed “not money!”)

Each of those instruments behave independently and uniquely, confounding any discussion of money.

It seems to me a bloody-minded discipline specifying exactly what is what may be very difficult, but not too difficult, and crucial. Maybe someone should catalog each instrument misnamed money, and then outline its behaviour in the wild.

Didn’t the Philosopher say something about first, define your terms?

John Spiers

Ron Paul used a very similar example during one of last’s year’s Republican debates – I forget which. Though I was at home watching on TV, based on the applause, I had the distinct impression that I was the only one (besides the good Doctor) who understood his point. Good to know there are others.

All of this however I would question whether FRB is a contributor to bubbles per se or whether Paul Markes oft repeated comment that (bank) loans should be from “real savings” is correct.

Banks do not practice “lending out of “thin air”.” as you suggest; banks have a deposit base, the aggregate of which in large part never gets repaid and much of which is interest free. This is not thin air, it is a highly illiquid practice but these are dormant resources that can be put to productive use.

In much the same way as a saver is normally one whose current income is more than is necessary for his current consumption and who can then pass the savings via a bank intermediary to one who has a need for current consumption beyond his current ability to produce, the banks are able to mibilise the dormant resources to productive sectors in the economy.

Look at it this way: A cheese warehouse has in aggregate a warehouse full of cheese at any one time. Cheeses come in and cheeses go out every day but in aggregate the warehouse is full.

The local bakery want to modernise and need a warehouse of cheese to barter for the bakery machinery and the cheese warehouse obliges. A great “liquidity” risk but the benefit to the economy of releasing the otherwise dormant resource is, more cheese on the market sends the price of cheese lower and more bread on the market makes bread cheaper.

What’s not to like?

waramess – “what is not to like” is that there is no such thing as a free lunch (although Milton Freidman lost sight of that himself).

If someone wants to spend to (for example) modernise a bakery then someone must SACRIFICE CONSUMPTION to enable this to happen.

If you try and finance the modernisation of the bakery without either the baker or some other REAL SAVER sacrificing consumption (clue – sacrificing consumption is what “saving” really means) then you have a CREDIT BUBBLE.

And the credit bubble must burst – the Gods of the Copybook Headings will not be denied.

There are no free lunches – reality is not optional.

As for whether “fractional reserve banking” should be legal (where the “fraction” is not nine tenths, as people seem to be believe – but rather NINTY TENTHS or NINE HUNDRED TENTHS of the real savings the bank has) that is a legal question – not a question of economics.

As long as the credit bubble banks are allowed to go BANKRUPT (no “suspension of cash payments” or other government backed legal trickery) I do not care whether FRB is legal or not.

“sacrifice consumption” is a bit emotional. I prefer to look at savings as income exceeding expenditure with the excess being passed (through bank intermediation)) to someone whose expenditure exceeds their income (a nice zero sum game).

There is little difference between a “savings account” and the amount of short term money (however short) that remains in aggregate on the banks’ books in perpetuity (an aggregate sacrifice, if you like), save that the latter might be there for longer.

This is not an exercise in free lunches it is instead how to make the most of the existing lunch, ie don’t leave the pie crust on the side of your plate.

You can see from the cheese example that initially the influx of new credit results in devaluation of the cheese (use gold or even money as a substitute example) but once done, because it is an existing resource, it is a once and for all effect but the benefit to production will be continual and capable of infinite repetition without an inflationary effect.

Since bamks are not able to create money (only the Central Bank has that ability) the process of creating credit from short term deposits has only a positive effect. The use to which it is put is an entirely different matter.

Friedmans error was to assume that an increase in money would inevitably lead to an increase in production. Now that certainly looks like someone looking for a free lunch and would certainly result in inflation.

Short version.

If someone shows you a new investment (or a new piece of consumption) there must be the question of “what was sacrificed to pay for this?”

If the answer is “nothing was sacrificed” – then one is in the presence of a con.

Certainly total production can be increased (wealth is not a fixed pie) – but investment can only take place if there is a sacrifice of consumption.

And (or course) all consumption (including all that house buying the government loves) has to be paid for also.

“sacrifice consumption” is not “emotional” – it is what real saving happens to be.

You might as well say “liquid is wet” is an “emotional” statement – and offer me a solid dry material as “liquid”.

As for the claim that the “creation of credit” (OVER AND ABOVE real savings) is a “positive” act……

If by “positive” you mean “to the long term benefit of the economy” then you are wrong – flat wrong.

The creation of credit (over and above real savings) is the creation of a credit bubble – and boom-bust is not to the long term benefit of the economy.

I repeat…..

If you want to borrow money (either for consumption or for investment)then someone else must save (really save) that money – i.e. SACRIFICE CONSUMPTION.

If you try and finance borrowing by “credit expansion” you are engaging in folly.