“Let us learn our lessons. Never, never, never believe any war will be smooth and easy, or that anyone who embarks on that strange voyage can measure the tides and hurricanes he will encounter. The statesman who yields to war fever must realise that once the signal is given, he is no longer the master of policy but the slave of unforeseeable and uncontrollable events.

“Antiquated War Offices, weak, incompetent or arrogant commanders, untrustworthy allies, hostile neutrals, malignant fortune, ugly surprises, awful miscalculations – all take their seats at the Council Board on the morrow of a declaration of war. Always remember, however sure you are that you can easily win, that there would not be a war if the other man did not think he also had a chance.”

Winston Churchill, ‘My Early Life’, quoted by Charles Lucas in a letter to the FT, 23rd July 2014.

And there is a war being conducted out there in the financial markets, too, a war between debtors and creditors, between governments and taxpayers, between banks and depositors, between the errors of the past and the hopes of the future. How can investors end up on the winning side ? History would seem to have the answers.

For history, read in particular James O’Shaughnessy’s magisterial study of market data, ‘What Works on Wall Street’ (hat-tip to Abbington Investment Group’s Peter Van Dessel). O’Shaughnessy offers rigorous analysis of innumerable equity market strategies, but we are instinctively and philosophically drawn most strongly towards the value factors highlighted hereafter.

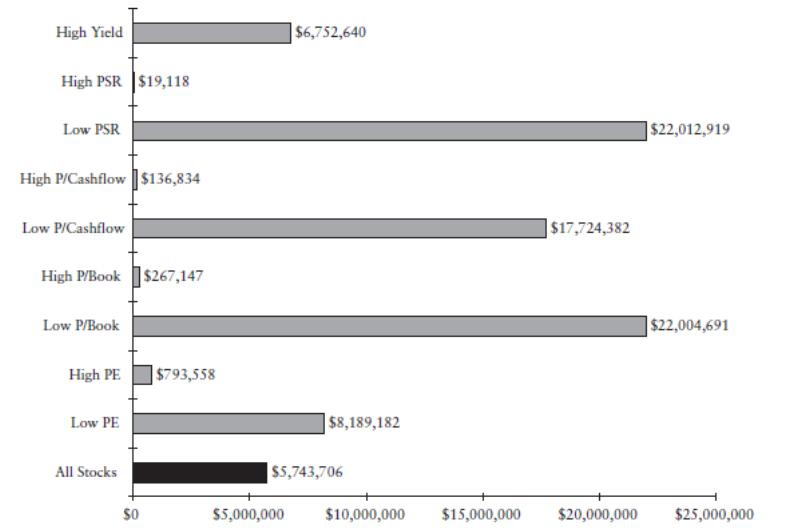

The chart below shows the results accruing to various strategies across the All Stocks universe – all companies in the Standard & Poor’s Compustat database with market capitalisations above $150 million, a dataset which comprises between 4,000 and 5,000 individual companies. The analysis takes in over half a century’s worth of data.

Making the (fairly reasonable) assumption that the data in this study is sufficiently broad to mitigate the effects of shorter term market “noise”, the results are unequivocal. Buying stocks with high price-to-sales (PSR) ratios; buying stocks with high price / cashflow ratios; buying stocks with high price / book ratios; buying stocks with high price / earnings (PE) ratios; all of these are disastrous strategies relative to the performance of the broad index itself. Caution: these all happen to be ‘growth’ strategies.

Value of $10,000 invested in various strategies using the All Stocks universe, from January 1951 to December 2003

(Source: What Works on Wall Street by James P. O’Shaughnessy, Third Edition, McGraw-Hill 2005)

But the converse is also true – in spades. Buying stocks with low price-to-sales ratios; buying stocks with low price / book ratios; these are both outstandingly successful strategies over the longer term, converting that initial $10,000 into over $22 million in each case. Buying stocks on low price / cashflow ratios is also a winning strategy. The relatively simple ‘high yield’ and ‘low p/e’ strategies also comfortably outperform the broad market. Note that these are all ‘value’ strategies.

This leads O’Shaughnessy to question the legitimacy of the so-called Capital Asset Pricing Model, in which investors are compensated for taking more risk:

“..the higher risk of the high P/Es, price-to-book, price-to-cashflow, and PSRs went uncompensated. Indeed, each of the strategies significantly underperformed the All Stocks Universe.”

Perhaps the market is indeed less efficient than certain academics would have us believe. The world’s most successful investor, Warren Buffett, would seem to think so. As he was quoted in a 1995 issue of Fortune magazine,

“I’d be a bum on the street with a tin cup if the markets were always efficient.”

And note that careful addition of the word “always”. Buffett wasn’t even going so far as to suggest that the markets are never efficient, but rather that the patient investor can take advantage of Mr. Market’s occasional lapses into the realms of absurdity, whether in the form of bullishness or outright despair.

O’Shaughnessy frames the returns from these various ‘growth’ and ‘value’ strategies more explicitly in the chart below.

Compound average annual rates of return across various strategies for the 52 years ending in December 2003

(Source: What Works on Wall Street by James P. O’Shaughnessy, Third Edition, McGraw-Hill 2005)

Special pleaders on the part of ‘growth at any cost’ might argue that the time series is insufficient. But if 52 recent years – easily an investor’s lifetime – taking in at least two grinding bear markets are not enough, how much would be ?

Again, the conclusions are clear. Buying stocks on low price-to-sales ratios is a winner, tying with stocks on a low price-to-book ratio with an annualised return over the longer term of 15.95%. Low price-to-cashflow is also a stellar performer. Buying stocks with a high yield also beats the broad market, as does buying stocks with low price / earnings ratios. Again, these are all explicit ‘value’ strategies.

Since we appear to be living through something of a speculative bubble (a bubble inflated quite deliberately by explicit central bank action), it is worth recalling one prior instance of ‘growth’ outperforming. As O’Shaughnessy points out,

“Between January 1, 1997 and March 31, 2000, the 50 stocks from the All Stocks universe with the highest P/E ratios compounded at 46.69 percent per year, turning $10,000 into $34,735 in three years and three months. Other speculative names did equally as well, with the 50 stocks from All Stocks with the highest price-to-book ratios growing a $10,000 investment into $33,248, a compound return of 44.72 percent. All the highest valuation stocks trounced All Stocks over that brief period, leaving those focusing on the shorter term to think that maybe it really was different this time. But anyone familiar with past market bubbles knows that ultimately, the laws of economics reassert their grip on market activity. Investors back in 2000 would have done well to remember Horace’s Ars Poetica, in which he states: “Many shall be restored that are now fallen, and many shall fall that are now in honour.”

“For fall they did, and they fell hard. A near-sighted investor entering the market at its peak in March of 2000 would face true devastation. A $10,000 investment in the 50 stocks with the highest price-to-sales ratios from the All Stocks universe would have been worth a mere $526 at the end of March 2003..

“You must always consider risk before investing in strategies that buy stocks significantly different from the market. Remember that high risk does not always mean high reward. All the higher-risk strategies are eventually dashed on the rocks..”

This might seem to imply that there is safety simply in the avoidance of explicitly high-risk strategies, but we would go further. We would argue today that central bank bubble-blowing has made the entire market high-risk, with a broad consensus that with interest rates at 300-year lows and bonds hysterically overpriced and facing the prospect of interest rate rises to boot, stocks are now “the only game in town”. We concede that by a process of logic and elimination, selective stocks look way more attractive than most other traditional assets, but the emphasis has to be on that word “selective”. We see almost no attraction in stock markets per se, and we are interested solely in what might be called ‘special situations’ (notably, in ‘value’ and ‘deep value’ strategies) wherever they can be identified throughout the world. We note, in passing, that markets such as those of the US appear to be virtually bereft of such ‘value’ opportunities, whereas those in Asia and Japan seem to offer them in relative abundance. In this financial war, we would prefer to be on the side of the victors. If history is any guide, the identity of the losers seems to be self-evident.