“Anything can happen in stock markets and you ought to conduct your affairs so that if the most extraordinary events happen, you’re still around to play the next day.”

Warren Buffett.

Vice Admiral James Stockdale has a good claim to have been one of the most extraordinary Americans ever to have lived. On September 9th, 1965 he was shot down over North Vietnam and seized by a mob. Having broken a bone in his back ejecting from his plane he had his leg broken and his arm badly injured. He would spend the next seven years in Hoa Lo Prison, the infamous “Hanoi Hilton”. The physical brutality was unspeakable, and the mental torture never stopped. He would be kept in solitary confinement, in total darkness, for four years. He would be kept in heavy leg-irons for two years, on a starvation diet, deprived even of letters from home. Throughout it all, Stockdale was stoic. When told he would be paraded in front of foreign journalists, he slashed his own scalp with a razor and beat himself in the face with a wooden stool so that he would be unrecognisable and useless to the enemy’s press. When he discovered that his fellow prisoners were being tortured to death, he slashed his wrists to show his torturers that he would not submit to them. When his guards finally realised that he would die before cooperating, they relented. The torture of American prisoners ended, and the treatment of all American prisoners of war improved. After being released in 1973, Stockdale was awarded the Medal of Honour. He was one of the most decorated officers in US naval history, with 26 personal combat decorations, including four Silver Stars. Jim Collins, author of the influential study of US businesses, ‘Good to Great’, interviewed Stockdale during his research for the book. How had he found the courage to survive those long, dark years ?

“I never lost faith in the end of the story,” replied Stockdale.

“I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining moment of my life, which in retrospect, I would not trade.”

Collins was silent for a few minutes. The two men walked along, Stockdale with a heavy limp, swinging a stiff leg that had never properly recovered from repeated torture. Finally, Collins went on to ask another question. Who didn’t make it out ?

“Oh, that’s easy,” replied Stockdale. “The optimists.”

Collins was confused.

“The optimists. Oh, they were the ones who said, ‘We’re going to be out by Christmas.’ And Christmas would come, and Christmas would go. Then they’d say, ‘We’re going to be out by Easter.’ And Easter would come, and Easter would go. And then Thanksgiving. And then it would be Christmas again. And they died of a broken heart.”

As the two men walked slowly onward, Stockdale turned to Collins.

“This is a very important lesson. You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end – which you can never afford to lose – with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

As Collins’ book came to be published, this observation came to be known as the Stockdale Paradox. For Collins, it was exactly the same sort of behaviour displayed by those company founders who had led their businesses through thick and thin. The alternative was the average managers at also-ran companies that enjoyed average returns at best, or that failed completely.

At the risk of stating the blindingly obvious, this is hardly a ‘good news’ market. Ebola. Ukraine. Iraq. Gaza. In a more narrowly financial sphere, the euro zone economy looks to be slowing, with Italy flirting with a triple dip recession, Portugal suffering a renewed banking crisis, and the ECB on the brink of rolling out QE. If government bond yields are a reflection of investor confidence, the fact that two-year German rates have gone below zero is hardly inspiring.

And we have had interest rates held at emergency levels for five years now – gently igniting who knows what form of as yet unseen problems to come. In Europe interest rates seem set to stay low or go even lower. But in the UK and the US, the markets nervously await the first rate hike of a new cycle while central bankers bluster and dither.

What are the implications for global asset allocation and stock selection ?

Both in absolute terms and relative to equities, most bond markets (notably the Anglo-Saxon) are ridiculously overvalued. Since the risk-free rate has now become the return-free risk, cash now looks like the superior asset class diversifier.

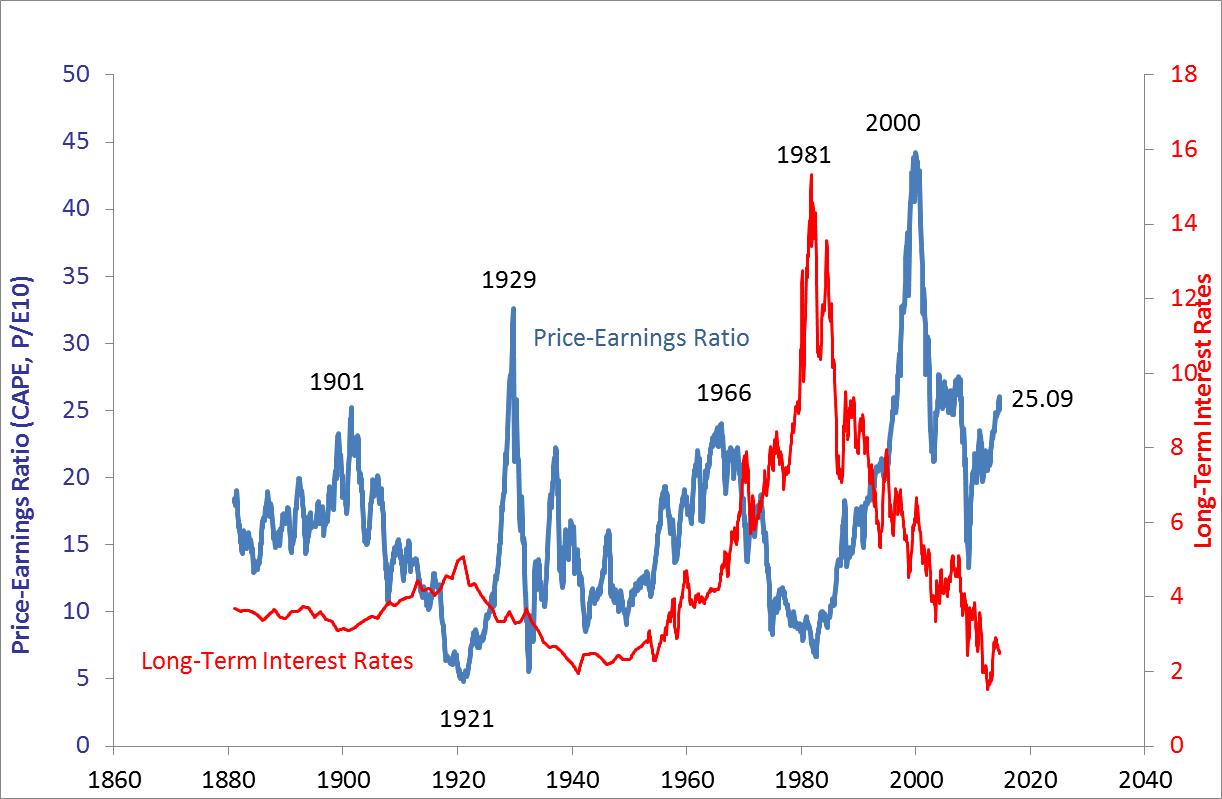

As regards stock markets, price is what you pay, and value (or lack thereof) is what you get. On any fair analysis, the US market in particular is a fly in search of a windscreen. Using Professor Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price / earnings ratio for the broad US stock market, shown below, US stocks have only been more expensive than they are today on two occasions in the past 130 years: in 1929, and in 2000. The peak-to-trough fall for the Dow Jones Industrial Average from 1929 equated to 89%. The peak-to-trough fall for the Dow from 2000 equated to “just” 38%. Time will tell just how disappointing (both by scale and by duration) the coming years will be for US equity market bulls.

But we’re not interested in markets per se – we’re interested in value opportunities incorporating a margin of safety. If the geographic allocations within Greg Fisher’s Asian Prosperity Fund are any guide, those value opportunities are currently most numerous in Japan and Vietnam. In the fund’s latest report he writes:

“Interestingly, and despite China’s continued underperformance, the Asian markets in aggregate have done better at this stage in 2014 than last year, while other global markets have fared less well. In our view the reason is simple – a combination of more attractive valuations than western markets, especially the US, but also, compared with 12-18 months ago, recognisably poor investor sentiment and consequently under-positioning in Asia, leading to the chance of positive surprises.”

Cylically adjusted price / earnings ratio for the S&P 500 Index

Source: www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data/ie_data.xls

The Asian Prosperity Fund is practically a poster child for the opportunity inherent in global, unconstrained, Ben Graham-style value investing. Its average price / earnings ratio stands at 9x (versus 18x for the FTSE 100 and 17x for the S&P 500); its price / book ratio stands at just one; historic return on equity is an attractive 15%; average dividend yield stands at 4.2%. And this from a region where long-term economic growth seems entirely plausible rather than a delusional fantasy.

Vice Admiral Stockdale was unequivocal: while we need to confront the “brutal facts” of the marketplace, we also need to keep faith that we will prevail. To us, that boils down to avoiding conspicuous overvaluation (in most bond markets, for example, and a significant portion of the developed equity markets) and embracing equally conspicuous value – where poor sentiment is likely to intensify subsequent returns. In this uniquely oppressive financial environment, with the skies darkening with the prospect of a turn in the interest rate cycle, we think optimism could be fatal. Or as Warren Buffett once observed,

“You pay a very high price in the stock market for a cheery consensus.”