One of the great economic myths of our time is Japan’s “lost decades.” As Japan doubles-down on inflationary stimulus, it’s worth reviewing the facts.

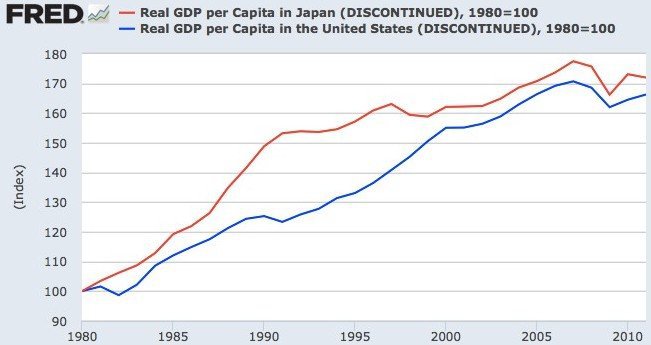

The truth is that the Japanese and US economies have performed in lock-step since 2000, and their performances have matched each other going as far back as 1980.

Either Japan’s not in crisis, or the US has been in crisis for a good thirty-five years. You can’t have it both ways.

Here’s a chart of per capita real GDP for both Japan and the US from 2000 to 2011. Per capita real GDP is the GDP measure that best answers the question: “is the typical person getting richer?”

The two curves look like they came from the same country:

Next, we can go back to 1980, to see where the myth came from. Japan was just entering its “bubble” decade:

We can see what happened here: Japan had a boom in the 1980s, then Japan busted while the Americans had their turn at a boom. By 2000 the US caught up, and Japan and the US synched up and shadowed each other, reflecting boom followed by the inevitable bust.

The only way you can get to the “lost decades” story is if you start your chart exactly when Japan was busting and America booming. Unsurprisingly, this is standard practice of the “lost decades” storytellers.

Of course, this would be like timing two runners, and starting the clock when one of them is on break. It’s absurd, but it gives the answer they want.

Things get worse when you include the artificial effects of inflation and population. Higher inflation and population growth both make the economy appear bigger without making people richer. If America annexed Mexico tomorrow, the US economy would grow by 30 percent. But that’s not going to make the average American 30 percent richer.

Adjusting for inflation and population is Macro 101. It’s so basic, in fact, that we might wonder if the “lost decades” macroeconomists are being intentionally forgetful. Why on earth would they do that?

Who Benefits from the “Lost Decades” Myth?

Who promotes the “lost decades” myth? Are the storytellers trying to make Japan look bad, or the US look good?

I suspect it’s a little of both: politicians in Japan need the sense of crisis to push their vote-buying schemes. It’s a lot easier to sell harmful policies if you can just convince the voters that everything’s already fallen apart. They’ve got nothing to lose at that point. In a crisis we are all socialists.

This cynical PR campaign is bearing fruit already, as Japanese voters accept inflationary policies from their new prime minister. In the name of reviving an economy that’s supposedly on its death-bed. Hard-working Japanese are losing their savings through low rates and inflation, but honor demands sacrifice so long as the future of the children supposedly hangs in the balance.

In reality, the re-telling of Japan’s myth reminds one of a doctor who lies to a patient so he can sell a cure that harms the patient.

On the American side, the myth of Japan’s “lost decades” is similarly useful: it makes our economic overlords seem like they actually know what they’re doing. And it serves to warn the naysayers: the “lost decades” myth is a bogeyman waiting to pounce if we ever falter from our bail-outs and vote-buying stimulus.

The truth, hidden in plain view, is that Japan’s not bad enough to be a battering ram for Japan’s Keynesian vote-buyers, and the US economy isn’t good enough for our home-grown vote-buyers to keep their jobs.

What a reveleation!

What it tells us is to be very careful to check the facts – always.

So a zero inflation rate is not harmful after all?