“Je ne suis pas Charlie. I am not Charlie, I am not brave enough.

“Across the world, and certainly across Twitter, people are showing solidarity with the murdered journalists of satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo, proclaiming in black and white that they too share the values that got the cartoonists killed. Emotionally and morally I am entirely with that collective display — but actually I and almost all those declaring their solidarity are not Charlie because we simply do not have their courage.

“Charlie Hebdo’s leaders were much, much braver than most of us; maddeningly, preposterously and — in the light of their barbarous end — recklessly brave. The kind of impossibly courageous people who actually change the world. As George Bernard Shaw noted, the “reasonable man adapts himself to the world while the unreasonable man persists in trying to adapt the world to himself”, and therefore “all progress depends upon the unreasonable man”. Charlie Hebdo was the unreasonable man. It joined the battle that has largely been left to the police and security services..

“It is an easy thing to proclaim solidarity after their murder and it is heart-warming to see such a collective response. But in the end — like so many other examples of hashtag activism, like the #bringbackourgirls campaign over kidnapped Nigerian schoolchildren — it will not make a difference, except to make us feel better. Some took to the streets but most of those declaring themselves to be Charlie did so from the safety of a social media account. I don’t criticise them for wanting to do this; I just don’t think most of us have earned the right.”

“But the rest of us, like me, who sit safely in an office in western Europe — or all those in other professions who would never contemplate taking the kind of risks those French journalists took daily — we are not Charlie. We are just glad that someone had the courage to be.”

– Robert Shrimsley in the Financial Times, 8 January 2015.

“Your right to swing your arms ends just where the other man’s nose begins.”

– Zechariah Chafee , Jr.

“I do not agree with what you have to say, but I’ll defend to the death your right to say it.”

– Voltaire.

On All Saint’s Day, 1st November 1755, an earthquake measuring roughly 9 on the Richter scale struck the Portuguese capital, Lisbon. At least 30,000 people are estimated to have perished. A little over half an hour after the original quake, a tsunami engulfed the lower half of the city. Those not affected by the quake or the tsunami were then beset by a succession of fires, which burned for five days. 85% of Lisbon’s buildings were destroyed. Ripples from the earthquake were felt far afield. Finland and North Africa felt aftershocks; a smaller tsunami made landfall in Cornwall.

Such destruction had a follow-on impact, in both philosophical and theological terms. In June 1756, the Inquisition responded with an auto-da-fé – a witch-hunt, effectively, for heretics.

One, much-loved, novel happens to cover both of these events, along with a third, from March 1757, when the British Admiral John Byng was executed for cowardice in the face of the French enemy at the battle of Minorca. This inspired the famous line, “Dans ce pays-ci, il est bon de tuer de temps en temps un amiral pour encourager les autres”: “In this country, it is wise to kill an admiral from time to time to encourage the others.”

That novel was written by a Frenchman, François-Marie Arouet, in 1758. We know him better today by his nom de plume: Voltaire. And his satirical magnum opus that catalogued these various disasters was called ‘Candide’.

‘Candide’ is a triumph of the style of novel best described as ‘picaresque’. It’s crammed with eminently quotable lines – the ‘Pulp Fiction’ of its day, if you will. Candide himself is a naïf who wanders with wide-eyed innocence through a savage and corrupt world. But in its Professor Pangloss it offers us the perfect encapsulation of today’s rogue economist, the unworldly and confused academic whose misguided practice of a false science has dreadful implications for the rest of us. A good modern-day example would be Martin Wolf, the FT’s chief economics correspondent, who on Friday complained about the UK’s property planning regime being “Stalinist”. Mr Wolf should try looking in the mirror more often – he is an ardent supporter of Stalinist monetary policy, for example.

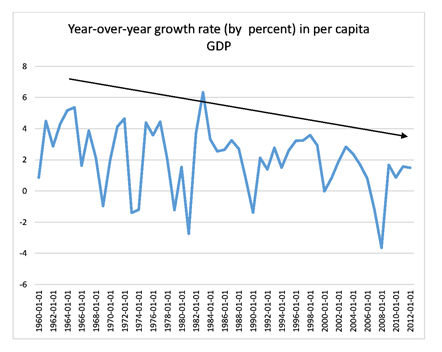

As investors we are all now the subjects of a grotesque monetary experiment. This experiment has never been tried before, and its outcome remains uncertain. The unproven thesis, however, runs something like this: six years into a second Great Depression, the only “solution” is for central banks to print ever greater amounts of money. Somehow, gifting free money to the banks that helped precipitate the crisis will lead to a ‘trickle down’ wealth effect. Instead of impoverishing those with savings, inflation will be some kind of miraculous curative, and it must be encouraged at all costs.

It bears repeating: we are in an extraordinary financial environment. In the words of the fund managers at Incrementum AG,

“We are currently on a journey to the outer reaches of the monetary universe.”

On January 25th, Greece goes to the polls. Greek voters face the unedifying choice of re-electing the buffoons who got the country into its current mess or electing rival buffoons issuing comparably ridiculous economic promises that cannot possibly be fulfilled. Voltaire would be in his element. But Greece is hardly alone. Just about every government in the euro zone fiddled its figures to qualify for membership of this not particularly exclusive club, and now the electorate of the euro zone is paying the price. Not that any of this is new news; the euro zone has been in crisis more or less since its inception. If it hadn’t been for sterling’s inglorious ethnic cleansing from the exchange rate mechanism in September 1992, the UK might be in the same boat. Happily, for once, the market was allowed to prevail. The market triumphed over the cloudy vision of bewildered politicians, and the British chancellor ended up singing in the bath. (That he had been a keen advocate of EMU and the single currency need not concern us – consistency or principles are not necessarily required amongst politicians.)

But the market – a quaint concept of a bygone age – has largely disappeared. It has been replaced throughout the West by bureaucratic manipulation of prices, in part known as QE but better described as financial repression. Anyone who thinks the bureaucrats are going to succeed in whatever Panglossian vision they’re pursuing would be well advised to read Schuettinger and Butler’s ‘Forty centuries of wage and price controls’. The clueless bureaucrat has a lot of history behind him. In each case it is a history of failure, but history is clearly not much taught – and certainly not respected – in bureaucratic circles these days. The Mises bookstore describes the book as a “popular guide to ridiculous economic policy from the ancient world to modern times. This outstanding history illustrates the utter futility of fighting the market process through legislation. It always uses despotic measures to yield socially catastrophic results.”

The subtitle of Schuettinger and Butler’s book is ‘How not to fight inflation’. But inflation isn’t the thing that our clueless bureaucrats are fighting. The war has shifted to one against deflation – because consumers clearly have to be protected from everyday lower prices.

Among the coverage of last week’s dreadful events in Paris, there has been surprisingly little discussion about the belief systems of religions other than Islam. We think that Stephen Roberts spoke a good deal of sense when he remarked to a person of faith:

“I contend that we are both atheists. I just believe in one fewer god than you do. When you understand why you dismiss all the other possible gods, you will understand why I dismiss yours.”

There is altogether too much worship of false gods in our economy and what remains of our market system. Some hubris amongst our technocratic “leaders” would be most welcome. Until we get it, the requirement to concentrate on only the most explicit examples of value remains the only thing in investment that makes any sense at all.

Love para 10…