Chapter 2

Extreme inequality is the main economic, political and cultural evil of our times. This chapter is about how bank-credit, as money newly-allocated and carrying an interest charge, increases inequality, transferring wealth and power from ordinary people to governments and the very rich. It is an old story, investigated in detail by the early American economists John Taylor, Daniel Raymond and William M. Gouge, but long since buried under arguments between competing advocates for big-State and big-business. Somewhere, the economics of what we live for in the West – freedom, democracy, equality, justice – have got lost.

The top dogs of wealth and power today are big state, big business – and finance, which once was just the ‘waggly tail’ but which increasingly wags both dogs. Inequality, and the sufferings of others, brings in consideration of ethics and justice. There is indeed an ethic supporting the new hierarchy, which says: ‘It is right that the few have so much money; they are the cleverest among us; their management of money amounts to genius and what’s more, they increase the overall prosperity of humanity’. The corollary of this is: ‘At the bottom of society are the feckless, the lazy, the incompetent, the stupid.’

Entirely buried under this ethic is the fact that the ultra-rich are beneficiaries of the ‘greatest system of theft and kleptocracy ever made legal and foisted upon the human race’ – a description of our monetary system provided for me by a leading banking lawyer. As outlined in the last chapter, this system consists of giving certain institutions the privilege of creating money in a way that profits and advantages the powerful. The losers are those who, for whatever reason, don’t join, serve or profit from this system: they may be inclined to live in freedom, morally and independently. After 300 years of circulating credit, this has become difficult.

One of the stranger things (of these strange times we live in) has been to watch governments, in a crisis caused by too much money in the wrong hands, pouring money into the same wrong hands via ‘quantitative easing’.

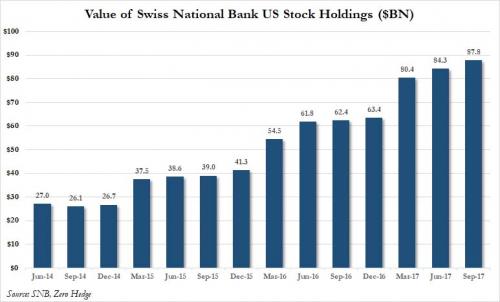

In quantitative easing, governments create brand-new money and use it to buy government debt (bonds) from large non-bank corporations (e.g. pension funds and insurance companies). The money (in the U.K. 375 billion; in the U.S. 3.5 trillion) does three things. First, by buying back government debt, the new money gives governments more leeway to spend. Second, it gives companies ready cash to buy other assets (stocks, corporate bonds, shares, buildings); this raises the price of capital assets generally, making rich individuals and corporations richer. Third, it gets banks out of trouble by refilling their ‘reserves’ free of charge when the company deposits its brand-new money: this makes it easier for banks to lend. In theory, banks will lend to businesses producing goods that people want to buy; but in our post-crunch world, most people have little excess money for spending and ‘productive enterprise’ is less profitable as a result, so most bank-lending goes to rich people to buy more assets. The price of those assets increases, and banks and investors again get richer.

Helped on by ‘quantitative easing’, inequality has now risen to almost incredible levels. There is a choice of statistics to express this inequality, most of them mind-boggling. An example: according to an Oxfam report (‘Working For The Few’, Jan 2014) the richest 85 individuals in the world are worth more than the poorest 3.5 billion. Another example: 25,000 people die from hunger each day, while a new billionaire is created every second day. From another angle: in 1983, the poorest 47% of America had $15,000 per family (2.5 percent of the nation’s wealth): in 2009, the poorest 47% of America owned zero percent of the nation’s wealth (their debts exceeded their assets).

The concentration of power and wealth in a very few individuals signifies a new social order. No rich individual is capable of day-to-day management of his/her own affairs: they are served by hierarchies of people and corporations. Many levels and branches of human and corporate ‘persons’ devote their working lives to maximising wealth at the tip. Laws are manipulated, taxes avoided, costs are cut, workers shed, regulations ‘captured’, environments destroyed, etcetera.

The poor are treated more and more exploitatively – and yes, with more and more contempt. Distant orders are given by departments devoted to cost-cutting and ‘efficiency’ – meaning more profit to shareholders; the state picks up the cost of these ‘efficiencies’. Overarching decisions affecting millions of lives are made at greater and greater remove by people who never have to witness the suffering and death they cause. This ‘remove’ is perhaps the most important factor in human affairs: if you are not close to the death or suffering your activities require, you can easily ignore it.

The bizarre and morally repulsive doctrine known as ‘austerity’ means cutting back on essential state-provided services. Poor and independent people, already bled into penury by the financial system, are deprived of the very basics of compensatory provision, and move from poverty to desperation so that kleptocrats may continue to get richer.

Perhaps just as strange, the alternatives offered by political parties in countries suffering economic devastation (Greece, Portugal, Italy) are reminiscent of left- and right-wing totalitarianisms of the last century. Extremist parties propose a greater role for the state in creating and controlling credit, taking it out of private hands. The outcome of this was well-demonstrated by the many and various communist and fascist regimes of the 20th century. The fifth plank of the communist manifesto was ‘Centralization of credit in the banks of the state, by means of a national bank with state capital and an exclusive monopoly’. The Nazis also sidelined commercial banks and created a State credit agency: it operated on Hjalmar Schacht’s premise: ‘quantity is hardly a problem in making credit available, as long as the credit-standing of the debtor, that is, his ability to make efficient use of the borrowed funds, is carefully considered.’ The result was on most counts, to coin a phrase, not good.

And all this is now taking place in what we like to call ‘democracies’!

There is a simple reason why no significant ‘just and reasonable’ alternative is on offer. The fundamentals of the financial system are far beneath the radar of public perception and debate; meanwhile, more and more complex ‘financial instruments’ grow from the fertile ground of ‘fictitious credit’ with the result that the visible manifestations of the system are more-or-less incomprehensible.

The American founding fathers were aware of much of this. John Adams wrote, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson: “All the perplexities, confusion and distresses in America arise not from defects in the constitution or confederation, nor from want of honor or virtue, as much from downright ignorance of the nature of coin, credit, and circulation.” How much more relevant are those words today!

The system today is similar to how it was in Adams’ day, only worse. Credit is 97% of money, whereas in his day it was considerably less than half. Chapter One examined the evolution of our bizarre system. Put simply, the government creates digital money (reserves) which the banks buy at auction. The banks then create claims on this digital money, and those claims – now called ‘credit’ – are rented out and become 97% of our money supply. To complete the picture, it is necessary to add that notes and coins are part of ‘reserve money’, purchased by banks and released to the public as a service to attract and keep customers. Otherwise, reserve money stays entirely within the banking system; only ‘credit’ may be owned outside it.

The main features of the system which contribute to inequality are these:

- 97% of our money supply is lent at interest. The profit goes to banks and spreads out, via investors, to increase the price of other capital assets (i.e. to making the rich richer). Again simply put (by John Taylor, friend and colleague of Jefferson and Adams) the interest paid to banks on our money supply is a ‘tax raised by the rich and powerful on the poor and the productive’.

- Governments borrow money (newly-created for them) from banks, by negotiation only with the banks themselves. The deal for the banks is: governments commit their citizens to pay interest, and to repay the loan at some time in the future. When the loan is repaid, the credit-money disappears, allowing the bank room to make a new loan. The new money gives spending-power to governments, which they allocate to whom they please, to political ‘friends’ and to buy voters, at the expense of productive citizens who must pay the price in taxes.

- The availability of borrowed money, newly-created in large amounts upon mere promise of a return, means that large corporations, which avoid paying taxes and influence law-making, borrow to prey on smaller, more efficient enterprises made vulnerable by the effects of (1) and (2).

The result has been a relentless growth in the dependence of citizens on large powers – on governments and private corporations. As the poor are reduced to below subsistence levels, so the government steps in to intervene and win votes. But the drift to inequality cannot be stopped without reforming the system; nor can independence, equity and justice be restored without the same.

Bank-currency has ramifications in many different areas of our lives. It not only relocates wealth; it relocates it to a specific type of person. Just as medieval feudalism gave power to individuals in every society devoted to war, so bank-currency gives it to individuals devoted to getting more money. Keynes looked optimistically to a world governed by a different, more equitable social ethic:

‘When the accumulation of wealth is no longer of high social importance, there will be great changes in the code of morals… The love of money as a possession – as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life – will be recognised for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity, one of those semi-criminal, semi-pathological propensities which one hands over with a shudder to the specialists in mental disease. All kinds of social customs and economic practices, which we now maintain at all costs because they are tremendously useful in promoting the accumulation of capital, we shall then be free, at last, to discard.’

Hip hip, hooray! But not yet.

When the system was just beginning, its character was obvious for all to see. It was praised by some and deplored by others – for identical reasons. It was ‘an excellent way to fund wars’: approved by some, deplored by others. It enabled financiers to ‘engrosse the commodities and merchandises of their own and other countries, so that none can be had but at the second hand’: approved by some, deplored by others. It lowered the interest rate at home, allowing capitalists to lend fictitious credit at higher rates abroad: ditto. It allowed ‘boundless power’ to financiers to lend to the government, thereby giving ‘boundless power’ to government too: ditto.

The predatory powers of created capital are as much at work between nations as they are inside nations. A country devoted to efficiency and production, and with an efficient banking system, lends money created out of nothing to a foreign government, which distributes it among voters and ‘friends’ to buy goods from the creditor country. Government is corrupted and voters get into debt along with all other citizens except a few ‘friends’ and pilfering government officials (who may relocate vast sums of money, perhaps to London, England or Florida – or anywhere else of their choice). Whole peoples become indebted and find their assets swallowed up by financial speculators: Greece is selling its temples and beaches, Italy is selling its marble mountains. A world-wide system of legalised robbery – of theft backed up by force of law – has been created by banking privilege.

As mentioned in the first chapter, the system was established internationally by laws ‘annexing certain privileges, benefits, and advantages to Promissory Notes… in order to promote public confidence in them, and thus to insure their circulation as a medium of pecuniary commercial transactions’. These ‘privileges, benefits and advantages’ may just as easily be taken away again, but only if citizens become familiar with reality. Three hundred years of history have shown that elites are happy for the truth to be buried deeper and deeper, not so much with lies as with a blind spot in public recognition, so that eventually it is never noticed at all.

Since banking practice was made legal, its workings have been overseen by regulators, not the justice system. Financial operators only come up against the law if their robbery oversteps the privileges already granted them and strays into legally-recognised fraud. The justice system is then obliged to confront some of the complexity which emerges once deceptive practices are legitimised. Two hundred years ago, the learned judge Lord Eldon had to decide between competing claims based on fictitious paper assets. ‘I must say that the speculations about paper certainly outran the grasp of the wits of courts of Justice,’ he remarked with lovely English understatement. The puzzle of how to deal with illegal fraud in the context of so much legal fraud is still with us: most perpetrators get off scot-free.

Very few people in a normal state of mind jump with excitement at the chance of learning about bank-money. But the system has transitioned from empire-building, oligarchy-creating to world-destroying, end-of-time stuff. It is time for reform. A terrible gap has opened up between the wonderment we could have created on Earth and the present situation, which can only be compared with the dream related by Procopius towards the end of the Roman Empire: the Emperor first consumes all that is good in the world and spews it out as excrement; then he consumes his own excrement, too.

But reform must be the subject of another chapter.

Ivo Mosley starts with the claim that private bank created money promotes inequality. He then launches forth on the subject of QE and the evils thereof. Well that doesn’t support the idea that privately created money promotes inequality – except for Ivo’s claim that QE increases bank reserves, which allegedly helps them lend. Unfortunately the latter idea is widely regarded as nonsense nowadays: Google the phrase “bank reserves” and “lend” and you’ll find dozens of articles debunking the claim that shortage of reserves constrains bank lending.

Ivo then claims that the interest charged by banks promotes inequality. Well if banks didn’t exist, the rich would still lend to the poor at interest, so it’s far from clear that banks actually PROMOTE inequality.

Well I’m half way thru Ivo’s article and I’m not impressed. That dissuades me from bothering with the second half.

My claim is that QE fills up bank reserves for free. If banks have no reserves, they cannot lend or engage in any kind of business. Normally they have to buy reserves. It sounds like you stopped at the right place – to avoid the discomforting obvious!