When even the eminent lawyer, Christine Lagarde, interrrupts her incessant calls for more ‘stimulus’ to confess that yes, peut-être, we ought to be on the look out for a bubble or two, you know things have reached a pretty pass.

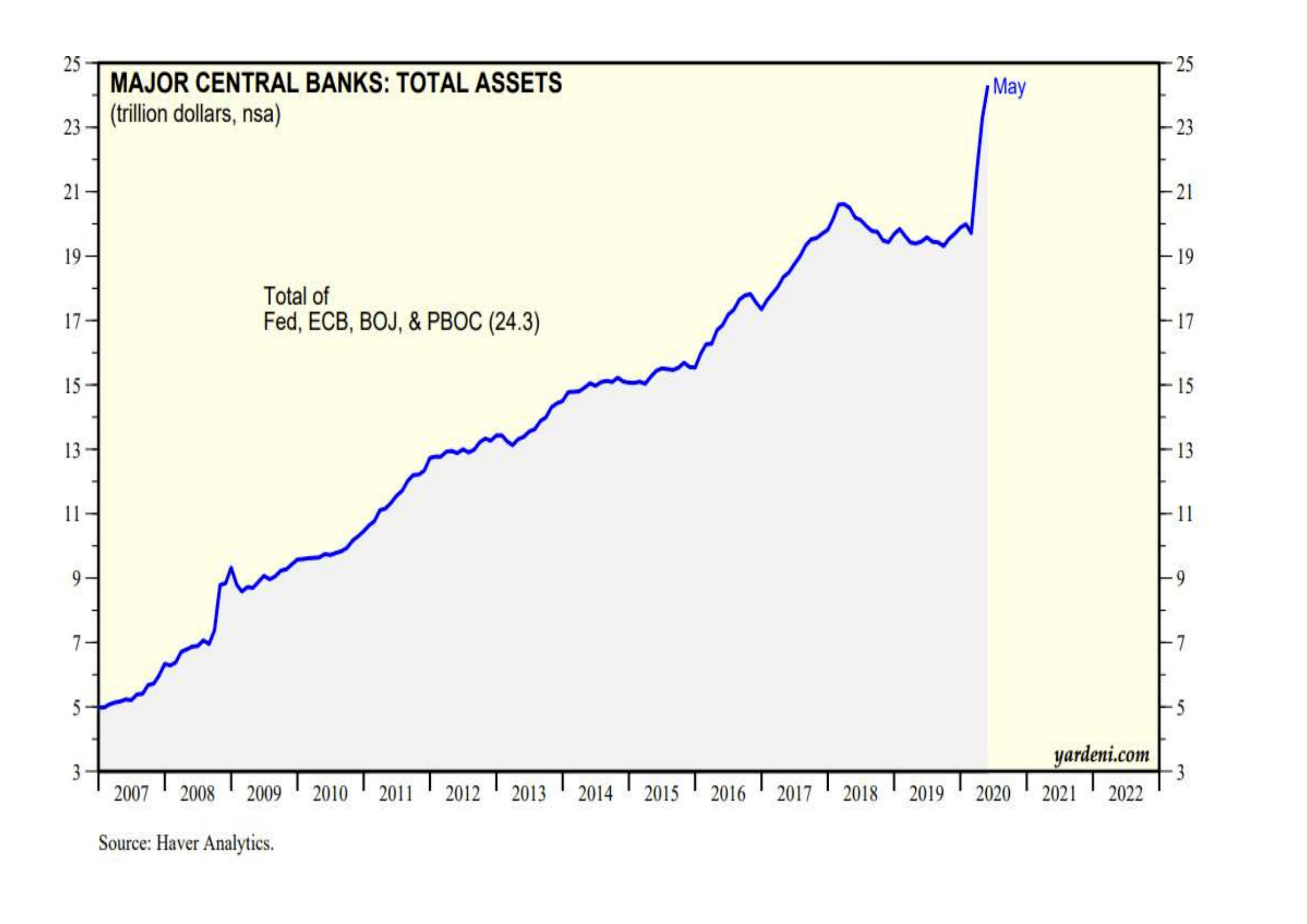

In truth, the awful effects of monetary overkill on the part of the major central banks seems finally to have reached a critical juncture, with asset markets everywhere spiralling rapidly out of control. We can only shudder to think what will await us if the inflationary spark ever manages to jump the firebreak of bad banks, zombiefied overcapacity, and ruined balance sheets and sets light to the markets for goods and services, too.

As regular readers know, our constant refrain has been that QEuro was a case of ‘too much, too late’. We said this not only because we deemed it utterly incapable of serving any practical purpose – since its one possible justification, that of thwarting a panicky threat to bank solvency, had long been absent from the stage – but also because we rightly feared it was far too pro-cyclical in financial market terms, where the quest for a one-way bet, carry-trade was already well advanced before Mario stepped up to deliver twos and twenties galore to the sharp-suited stewards of the plutocrats’ booty. [Claudio Borio at the BIS would clearly agree]

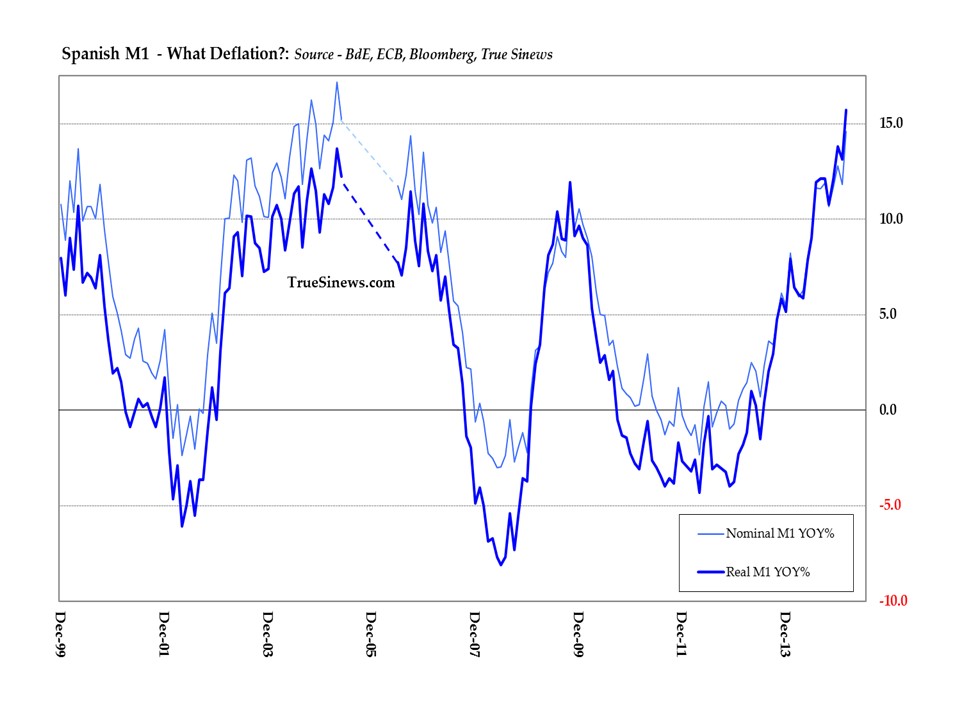

Even before Draghi lit the blue touchpaper, money supply was accelerating markedly everywhere except in poor old Greece. Across the Zone as a whole, the rise through the second half of last year and up to February was a gangbusters 15.5% annualized – a pace never exceeded in the history of the single currency and only once outmatche in the 35 years that the ECB back-calculates the series.

And, as we say, this has not been a phenomenon linked to the healthier of the economies alone. Look at what is happening in Spain where the increase in nominal M1 is at a 10-year high and that in real M1 is setting records. No wonder there has been a marked improvement (albeit from low levels) in general activity in the country.

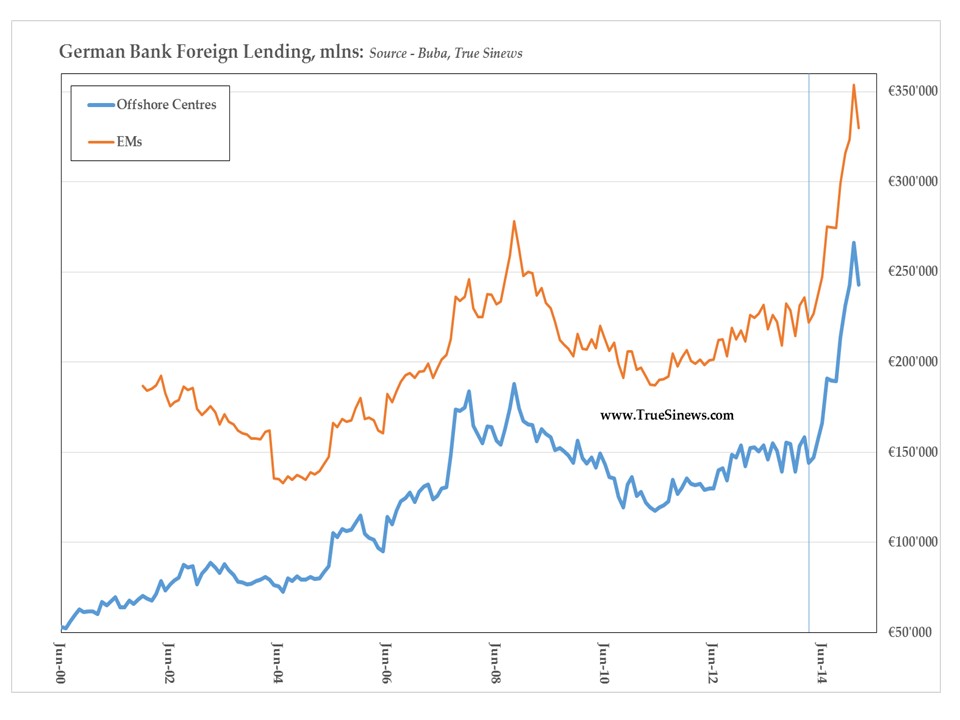

What is more, a good deal of money was already pouring out of the Zone and further boosting financial hyperactivity around the globe, long before te ECB decided to widen the global GINI coefficients. For example, between March last year and February this, German banks greatly increased their lending to regions outside the Eurozone. In fact, they channeled €120 billion to the hedge fund haven of the Cayman Isles – a region in which they hold as many assets as they do in France and Luxembourg – for a total which outstrips the funds lend to the US proper and which is second only to those parked in that other powerhouse of hot finance, the UK.

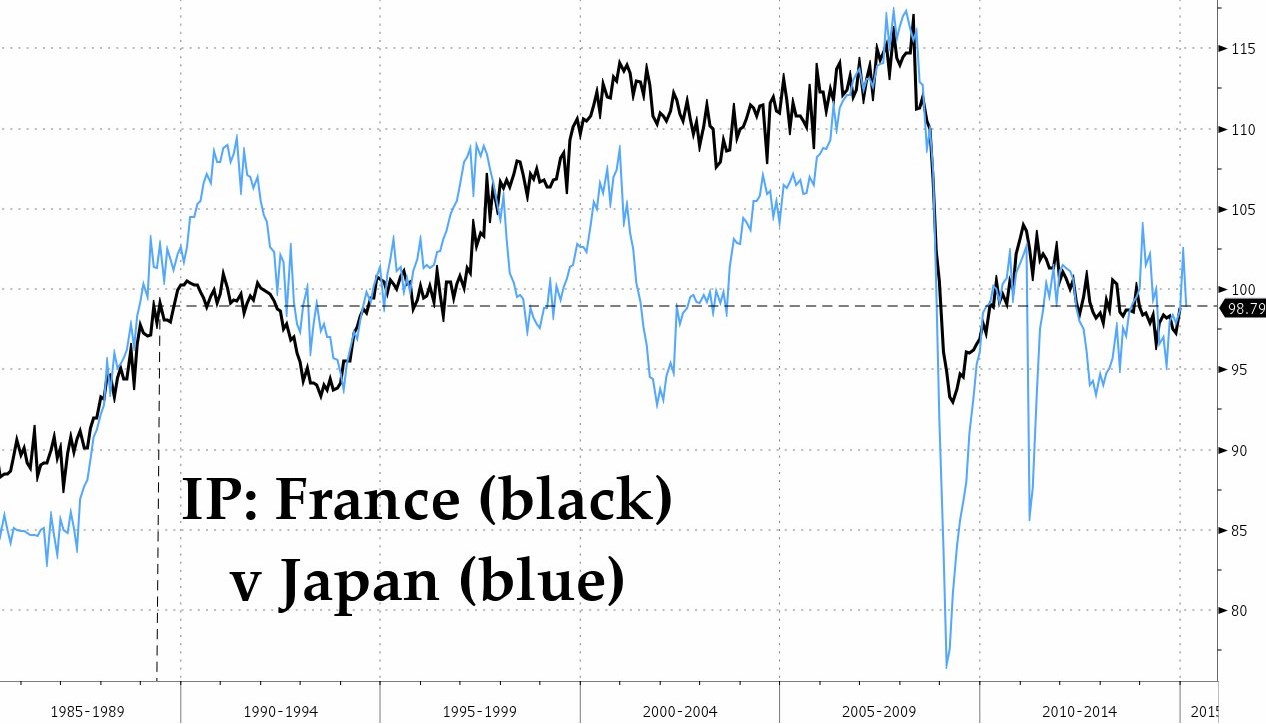

As ever, little of the new money is helping lubricate the wheels of industry. While orders, sales, and output in Germany are undeniably close to their highs (especially, but not only, if measured in a shrinking currency), they are fairly stagnant on that plateau. Even that is much better than the likes of France where – though decidedly less volatile – the trace of industrial production over the lost generation years has matched that seen in the archetypal basket case of Keynesian concrete-pouring, Japan.

Not that things are much better outside the Zone where, in the case of that Earthly Paradise of high-tax, purportedly functional egalitarianism, Sweden, a similar stagnation has set in – for reasons which still elude both Larry Summers and Ben Bernanke (and with which we shall deal in a forthcoming commentary).

In passing, Sweden is another case of that malaise where a tripling of the supply of money these past 16 years has accompanied zero overall increase in industrial output and where exports (adjusted for the fall in the krona) are again where they were back in 2007, so matching the performance during the slump which followed the banking crisis and the EMU conniptions of the early 90s.

To our mind, there is a demonstrable general tendency at work by which when liquidity improves (which we measure by looking at the relation between money and bank credit), revenue flows more directly to cash (rather than to accounts receivable and the like), business sentiment improves, and an enhanced level of real activity follows. Yet, worringly, over that same period of stasis, the ratio of Swedish M1 to the credit liabilities which make up the higher aggregates has increased 2 1/2 fold – all to little avail.

Never mind, though! Who needs dirty, smelly, old school entites like industries, anyway, when house prices are up by a quarter and the stock market is 80% higher? Who cares about actual wealth production?

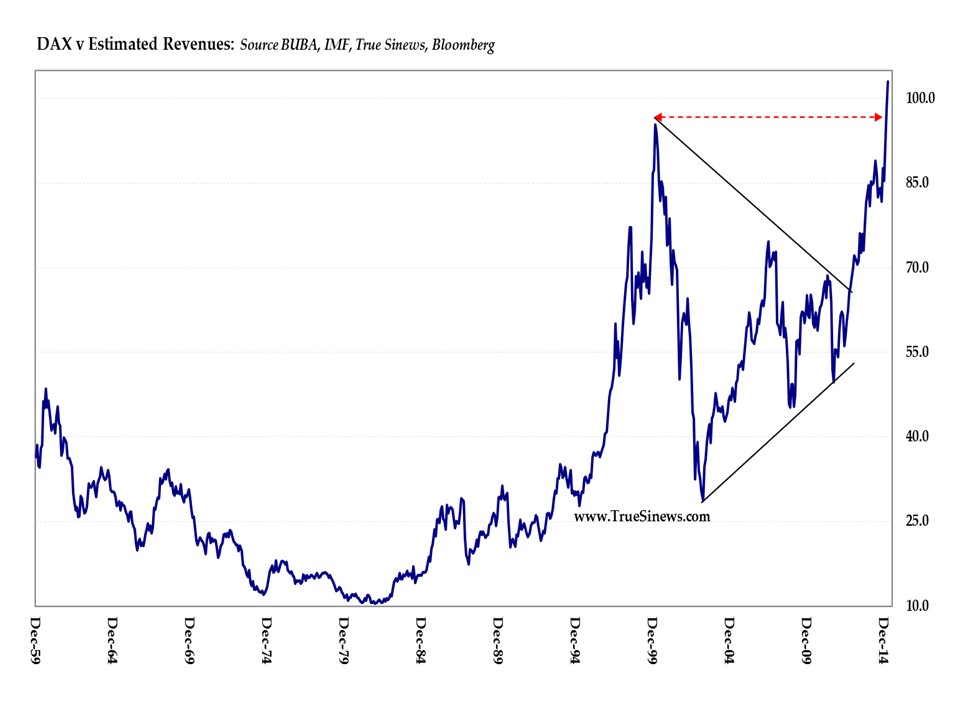

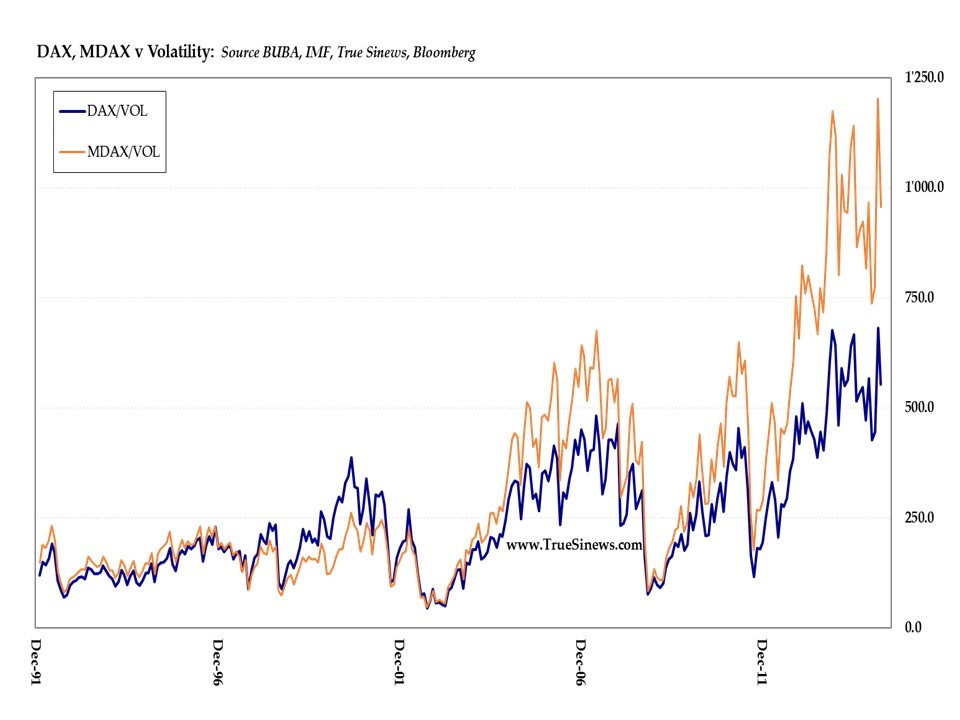

Not that the latter, Cantillonesque disconnect between nominal asset-collateral values and real income generation is a trait wholly confined to the Scandinavians. The same is true across much of Europe, sad to relate. Under the pernicious influence of artifically low bond yields, German equities, for example, are not only pushing the envelope in terms of pirce/earnings and price/book, but also in relation to the price people want to pay to protect against any possible setback in the market.

With all this frenzied buying going on, it is testimony to the degree of ECB overkill that the attraction of a stock market which is not only rising but which is still ostensibly less rich than its US counterpart has not been enough to prevent the euro from falling hard, once more, even absent any dramatic rise in the macroeconomic temperature of the States.

Were the present decline to break through the levels plumbed a month ago (around 1 1/2 big ones blow those prevailing at the time of writing), it would be significant indeed, marking a breech of the long-term channel/trend, the mean, and the mid point of the entire (top-heavy) distribution laid down by the DM, then the euro, since the break-up of Bretton Woods.

Were that to occur, we could soon see the linear fib at 9450 or even the geometric mid-point, Down at 9275, before very much longer.

Nice one, Mario!