There is a common view in financial markets that credit deflation is bad for gold prices, because gold nowadays is regarded as an asset to be sold in the scramble for cash when people are forced to pay down their debts.

When asked by Congressman Ron Paul his opinion on gold four years ago, Ben Bernanke replied it was not money, just another asset, appearing to confirm this view.

Doubtless Bernanke’s view is shared by nearly all other central bankers in the advanced economies and by executives in the banks which have profited handsomely from monetary and credit inflation. But it is not shared by the majority of ordinary savers around the world who see it still as the ultimate store of value at a time of fiat currency inflation. For them, gold is the money to save, driven out of circulation by inferior currencies. We know this to be true throughout Asia where the bulk of the world’s population lives; but even millions of ordinary Americans continue to accumulate silver eagles because they still recognise the monetary attributes of precious metals.

Crucially, the assumption in capital markets that gold is no longer money but just an asset or commodity has all but destroyed our understanding of its monetary relationships. Financial analysts fail to appreciate the difference in behaviour of sound money compared with that of unsound money during a contraction of bank credit. This can be empirically established by looking at the relationship between gold and the US dollar in the great depression, when bank credit contracted substantially after the Wall Street crash, and gold was then revalued upwards by 69% to $35 in 1935. The whole point of unsound money is that it can be devalued relative to sound money, as it was at that time, in order to stabilise prices that would otherwise fall; a policy option that is not available to central banks adhering to a gold standard.

In the days of a gold – or more correctly – a gold exchange standard, the collapse of excessive bank credit was always sudden, and vicious in proportion to the previous expansion. Since credit was expanded out of thin air by banks without underlying stocks of gold to cover it, inevitably slumping prices became associated with bank failures, and central banks were set up to insulate commercial banks from this brutal reality. Saving over-extended banks always requires the artificial lowering of interest rates and the expansion of the money quantity to restrain the currency’s purchasing power from rising against declining commodities. Gold therefore remains a store of value for savers because it cannot be devalued in this way by a central bank.

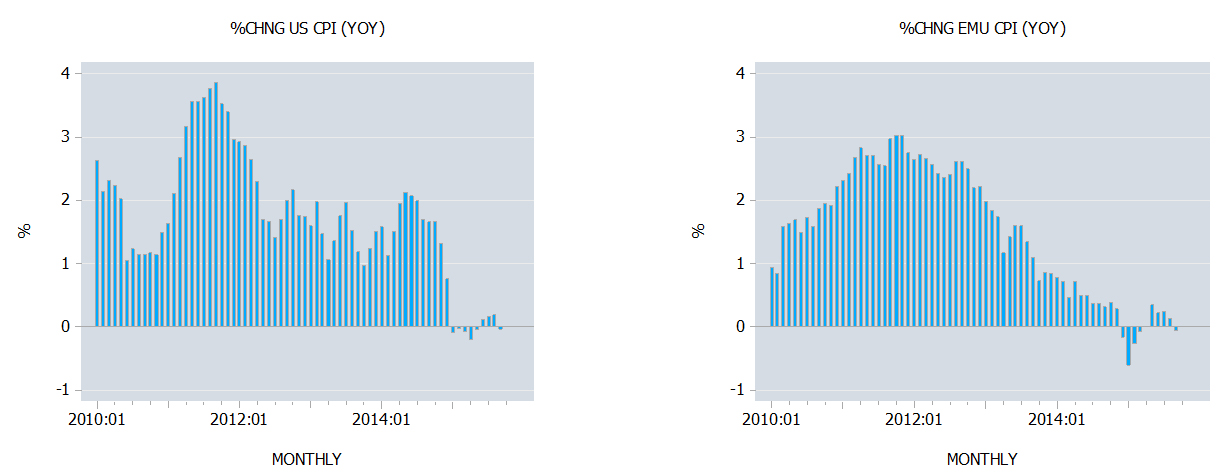

This is becoming relevant again given that the escalating credit problems in China appear to be leading towards a 1929-style stock market crash, which if it follows the well-established playbook, will be followed by an economic slump. Today China is the largest commercial consumer of commodities, just as America was in the late 1920s, and her slowing economy is putting downward pressure on commodity prices, pushing up the purchasing power of money of the other major currencies. Put another way, falling energy and commodity prices in yuan are forcing deflation upon the rest of us. So even though investors in gold have seen its dollar price trade broadly sideways for the last three years, its purchasing power measured against most commodities has actually been rising. More recently, gold has also been an effective store of value against weaker currencies, notably the euro and yen.

Now that China’s credit deflation is beginning to be exported to the US through lower commodity prices, there is a growing assumption that the dollar will strengthen further. This has encouraged hedge funds to sell gold futures to capture the dollar’s rise. In terms of purchasing power it is certainly true that the currency has a deflationary element in it. However, if the Federal Reserve refused to expand the quantity of dollars in circulation, abandoning commercial banks to face the full force of a credit contraction, the purchasing power of the dollar would rise as if it were sound money. But the Fed was set up to do the exact opposite, so it has a clear duty to weaken its currency in this event. Therefore, when the balance of risk swings towards a credit contraction in the US, gold will rise against the dollar because the Fed through its monetary policy is certain to ensure it does so.

This will also surprise market traders who think that a continuing collapse in Chinese stock markets will force liquidation of gold holdings by the Chinese public. There is little doubt that distressed speculators will come under pressure to sell gold if they own it, but this argument ignores the certainty that during a credit contraction government-issued currencies always weaken against gold. So having acquired substantial quantities of gold for itself and having also ensured it is widely held by its public, the Chinese government is arguably in a more compelling position to encourage a gold revaluation as a means of stabilising her economy in a credit crisis than America was eighty years ago. It will be China’s only option, and if the government doesn’t go for it, China’s middle classes certainly will.

We are already seeing the People’s Bank of China engaging in reflationary policies to contain the stock market crash. This is a normal central bank response. Doubtless it will maintain the managed peg against the US dollar, partly because China is committed to building confidence in her own currency as a replacement for the dollar in international settlements, and partly because currency devaluation would be seen in the markets as a failure of economic policy. Furthermore, China can reasonably expect US monetary policy to do some of its reflationary work for it.

Therefore, instead of devaluing against the dollar, a rise in the yuan gold price is almost certain to occur. Of course, whether or not China revalues her gold reserves remains to be seen, but allowing the price to rise fits in with the logic of the relationship between sound and unsound money when a credit contraction threatens to become a serious issue.

This simple fact could override all the geostrategic considerations upon which China-watchers have tended to focus. A gold revaluation would be presented to the world as bound up with China’s domestic economic problems, instead of an act aimed at undermining the dollar’s reserve status: a solution that is less confrontational than outright disagreement with Western central banks over gold’s role in the international monetary order.