Source: http://bawerk.net/2015/08/15/that-70s-show-episode-2/

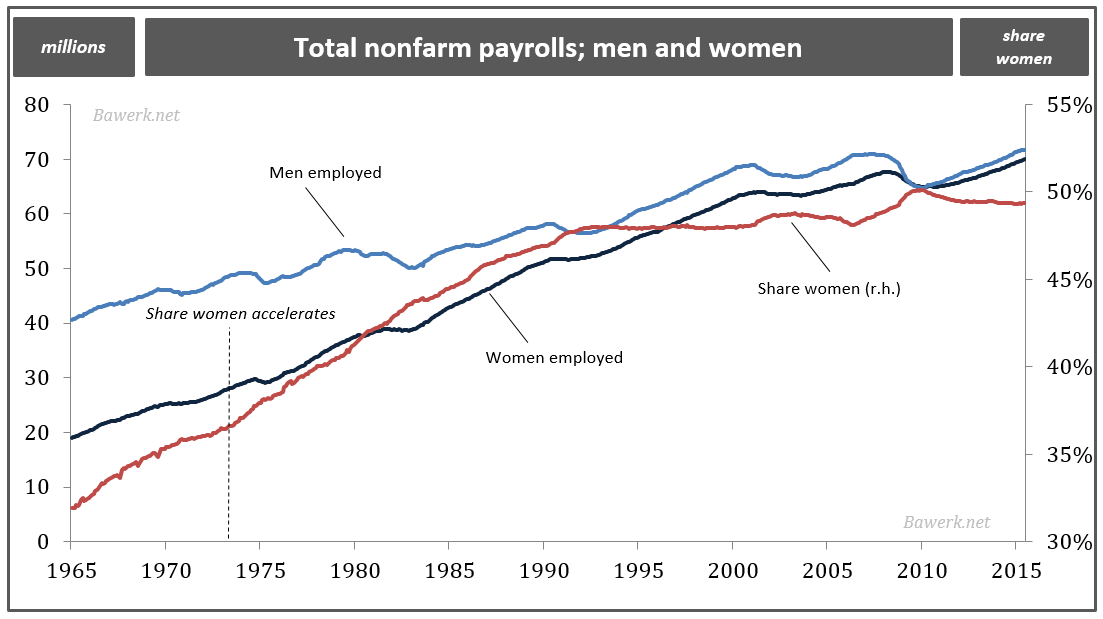

In Episode 1 we showed how the US labour market changed dramatically from the 1970s on back of excess money printing which allowed Americans to buy tradable goods on the international market, hollowing out its own manufacturing base, and essentially creating an unsustainable consumer driven economy where the broad masses get their employment within service sector.

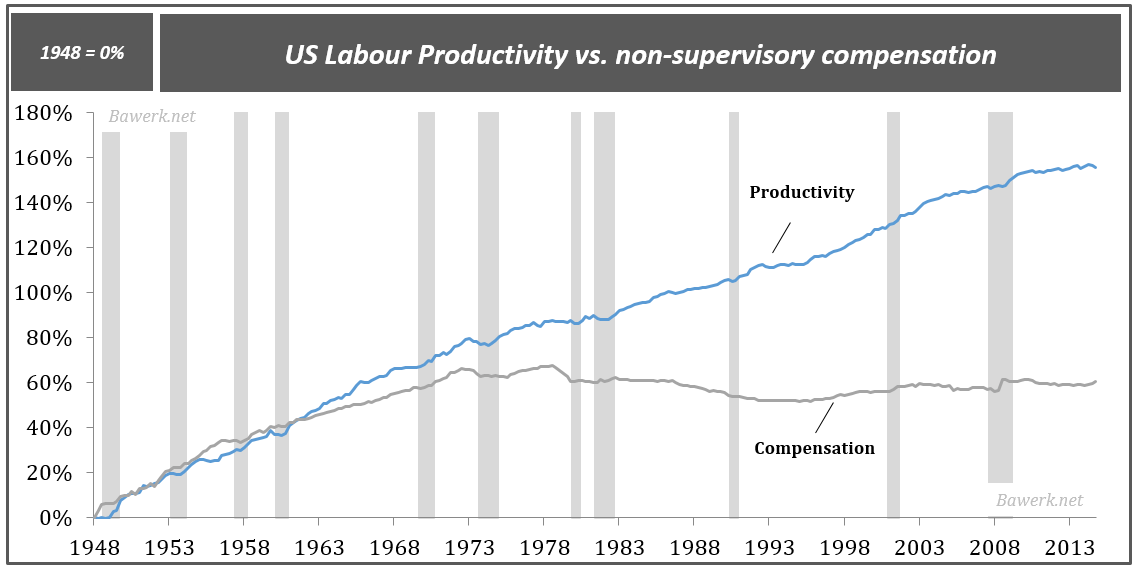

We will now take that a step further and look at what this has meant for the US worker. As our first chart shows, non-supervisory real wages stagnated in the early 1970s and has essentially remained flat ever since.

Measured labour productivity on the other hand continued upward, but its rate of growth shifted down. More on this in our next blog post.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Bawerk.net

The American middle class, i.e. the non-supervisory workers, managed to grow their consumption in the midst of stagnating wages through

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Bawerk.net

Source: Federal Reserve – Flow of funds Z.1, Bawerk.net

It should be clear that when the share of women in the labour force has reached 50 per cent and further leverage of a shrinking household income has become counterproductive the end-game has started. The only way to increase living standards from here will be the old fashioned way; consume less than you produce and productively invest the surplus.

This brings us back to the previous post, where we suggested the end-game will be one where global manufacturing powerhouses such as China, Japan and Germany will discover their overexposure to exports to the same extent that the US is overexposed to its service sector. As Americans start to save more, invest it domestically and rebuild their manufacturing base global exporters will be forced to do the opposite. Needless to say, this change will not come voluntarily, but through recession, financial crisis and necessity. Excesses must be liquidated at some point, no matter.

But why did US wages stagnate? Simple, through a Faustian bargain they traded highly productive jobs in the manufacturing sector for low productive jobs in the service sector. While it felt great at the time – we are all amazed to see the convenient lifestyle Americans live – it came with long term consequences.

As the US employment changed toward part-time, low benefit, low paid service sector jobs the quality in the overall labour market deteriorated. We have made a job quality index to depict just this. Unsurprisingly, this index, along with so many, peaks right after Bretton-Woods collapses. And the really scary thing is how it has completely fallen off a cliff in the period after the financial crisis.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Bawerk.net

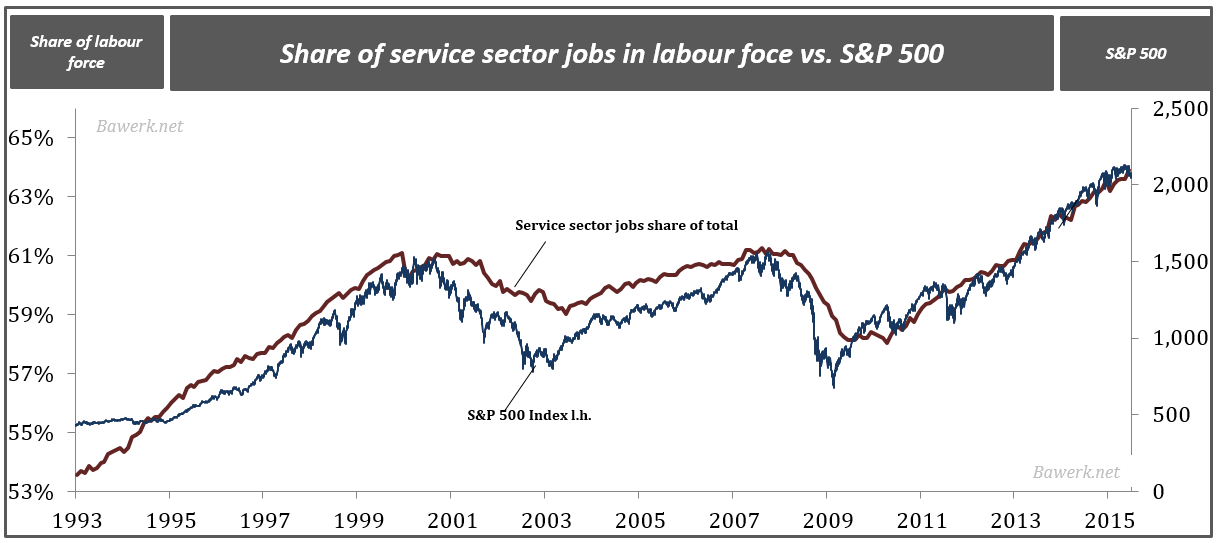

And while we could conclude this missive here, we will repeat an argument we made in How the FOMC got institutionally corrupt because it is a direct result of the changes that has occurred in the US labour market.

The so-called wealth effect that rules today’s macroeconomic model output brings quacks and charlatans like Greenspan to claim that stock market gains cause economic growth; perversely enough they are semi-right due to faulty concept of GDP and the way inflated asset values in the US can be used as leverage to purchases tradable goods on the international market. The last chart today talks volumes about what is going on in US policy circles, and why things have become as confused as they are.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Federal Reserve of St. Louis, Bawerk.net