To be sure, we’ve long contended that official data on bad loans at Chinese banks is even less reliable than NBS GDP prints. Indeed, the lengths Beijing goes to in order to obscure the extent to which banks’ balance sheets are in peril is truly something to behold and much like the deficient deflator math which may be causing the country to habitually overstate GDP growth, it’s not even clear that China could report the real numbers if it wanted to.

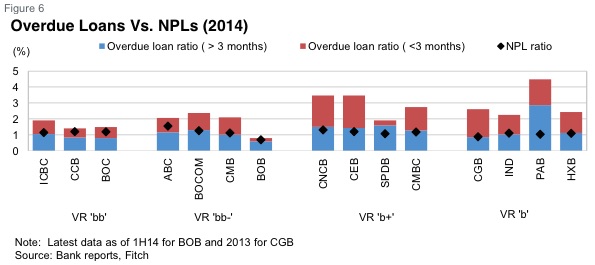

We took an in-depth look at the problem in “How China’s Banks Hide Trillions In Credit Risk: Full Frontal”, and we’ve revisited the issue on a number of occasions noting in August that according to a transcript of an internal meeting of the China Banking Regulatory Commission, bad loans jumped CNY322.2 billion in H1 to CNY1.8 trillion, a 36% increase. Of course that’s just the tip of the iceberg. In other words, that comes from a government agency and although the scope of the increase sounds serious, it still translates into an NPL ratio of just 1.82%. Here’s a look at the “official” numbers (note that when one includes doubtful accounts, the ratio jumps to somewhere in the neighborhood of 3-4%):

Source: Fitch

There are any number of reasons why those figures don’t even come close to approximating reality. For instance, there’s Beijing’s habit of compelling banks to roll over bad loans, and then there’s China’s massive (and by “massive” we mean CNY17 trillion) wealth management product industry which, when coupled with some creative accounting, allows Chinese banks to hold some 40% of credit risk off balance sheet.

Well as time goes on, and as market participants scrutinize the data coming out of the world’s second most important economy, quite a few analysts are beginning to take a closer look at the NPL data for Chinese banks. Indeed, if Beijing continues to move toward “allowing” defaults to occur (even at SOEs) and if China’s transition from smokestack economy to a consumption and services-driven model continues to put pressure on borrowers from the manufacturing sector, the situation is likely to deteriorate quickly. If you needed evidence of just how precarious things truly are, look no further than a recent report from Macquarie which showed that a quarter of Chinese firms with debt are currently unable to cover their annual interest expense (as you might imagine, it’s even worse for commodities firms).

Just two weeks after we highighted the Macquarie report, we took a look at research conducted by Hong-Kong based CLSA. Unsurprisingly, it turns out that Chinese banks’ bad debts ratio could be as high 8.1%, a whopping 6 times higher than the official 1.5% NPL level reported by China’s banking regulator.

We called that revelation China’s “neutron bomb” but it turns out we may have jumped the gun. According to Hong Kong-based “Autonomous Research”, the real figure may be closer to 21% when one takes into account the aforementioned shadow banking sector. Here’s more from Bloomberg:

Corporate investigator Violet Ho never put a lot of faith in the bad loan numbers reported by China’s banks.

Crisscrossing provinces from Shandong to Xinjiang, she’s seen too much — from the shell game of moving assets between affiliated companies to disguise the true state of their finances to cover-ups by bankers loath to admit that loans they made won’t be recovered.

The amount of bad debt piling up in China is at the center of a debate about whether the country will continue as a locomotive of global growth or sink into decades of stagnation like Japan after its credit bubble burst. Bank of China Ltd. reported on Thursday its biggest quarterly bad-loan provisions since going public in 2006.

Charlene Chu, who made her name at Fitch Ratings making bearish assessments of the risks from China’s credit explosion since 2008, is among those crunching the numbers.

While corporate investigator Ho relies on her observations from hitting the road, Chu and her colleagues at

Autonomous Research in Hong Kong take a top-down approach. They estimate how much money is being wasted after the nation began getting smaller and smaller economic returns on its credit from 2008. Their assessment is informed by data from economies such as Japan that have gone though similar debt explosions.

While traditional bank loans are not Chu’s prime focus — she looks at the wider picture, including shadow banking — she says her work suggests that nonperforming loans may be at 20 percent to 21 percent, or even higher.

“A financial crisis is by no means preordained, but if losses don’t manifest in financial sector losses, they will do so via slowing growth and deflation, as they did in Japan,” said Chu. “China is confronting a massive debt problem, the scale of which the world has never seen.”

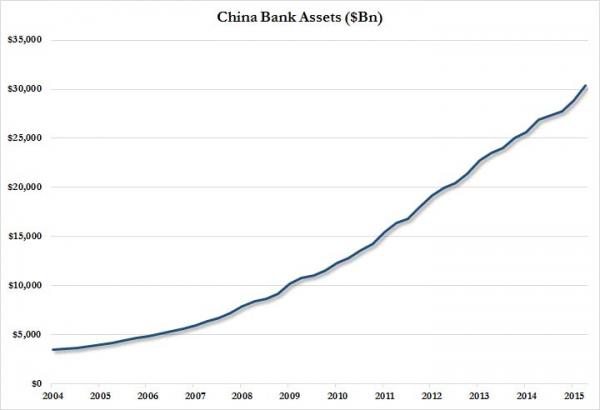

As a reminder, here’s a look at the scope of the “problem” Chu is describing:

And here’s a bit more on special mention loans and the ubiquitous practice of “evergreening”:

Slicing and dicing the official loan numbers, Christine Kuo, a senior vice president of Moody’s Investors Service in Hong Kong, focuses on trends in debts overdue for 90 days, rather than those classified as “nonperforming.” Another tactic some analysts use is to add nonperforming debt to “special mention” loans, those that are overdue but not yet classified as impaired, yielding a rate of 5.1 percent.

Banks’ bad-loan numbers are capped by “evergreening,” the practise of rolling over debt that isn’t repaid on time, according to experts including Keith Pogson, a Hong Kong-based senior partner at Ernst & Young LLP. Pogson was involved in restructuring debt at Chinese banks in 1998, when their NPL ratios were as high as 25 percent.

So let’s just be clear: if 8% is a “neutron bomb”, a 21% NPL ratio in China is the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. Here’s why:

If one very conservatively assumes that loans are about half of the total asset base (realistically 60-70%), and applies an 20% NPL to this number instead of the official 1.5% NPL estimate, the capital shortfall is a staggering $3 trillion.

That, as we suggested three weeks ago, may help to explain why round after round of liquidity injections (via RRR cuts, LTROs, and various short- and medium-term financing ops) haven’t done much to boost the credit impulse. In short, banks may be quietly soaking up the funds not to lend them out, but to plug a giant, $3 trillion, solvency shortfall.

In the end, we would actually venture to suggest that the real figure is probably far higher than 20%. There’s no way to get a read on how the country’s vast shadow banking complex plays into this but when you look at the numbers, it’s almost inconceivable to imagine that banks aren’t staring down sour loans at least on the order of a couple of trillion.

To the PBoC we say, “good luck plugging that gap” and to the rest of the world we say “beware, the engine of global growth and trade may be facing a pile of bad loans the size of Germany’s GDP.”

We close with the following from Kroll’s senior managing director in Hong Kong Violet Ho (quoted above):

“A credit report for a Chinese company is not worth the paper it’s written on.”