One can understand the Fed’s frustration over the failure of its interest rate policy, and its desire to escape the zero bound.

However, since the FOMC has all but said it will increase rates at its December meeting, events have turned against this course of action. The other major central banks are in easing mode, and the slowdown in China has further undermined both world trade flows and commodity prices. The result has been a strong dollar, which has effectively eliminated any perceived need for higher dollar interest rates. Meanwhile, the US’s non-financial economy remains subdued.

Last August, a similar situation existed, when the FOMC signalled that a rise in the Fed Funds Rate might be announced at its September meeting. Ahead of it, China revalued the dollar by announcing a small devaluation of its own currency, taking the wind out of the Fed’s sails. While the talking heads saw this as a failure of Chinese financial policy, it was nothing of the sort. Given the US was dragging its feet over the yuan’s inclusion in the SDR, it was a salvo in the financial war between the two states, and the Fed found itself in the firing line.

Since then the pressure has been mounting from the IMF for the US to back down over the SDR issue. The result was announced only this week, with the dollar content hardly changing and the yuan being accommodated mostly at the expense of the euro from September next year. However, despite the SDR issue having been dealt with for now, the Fed appears to have very little room for manoeuver before higher interest rates will give rise to a new financial crisis.

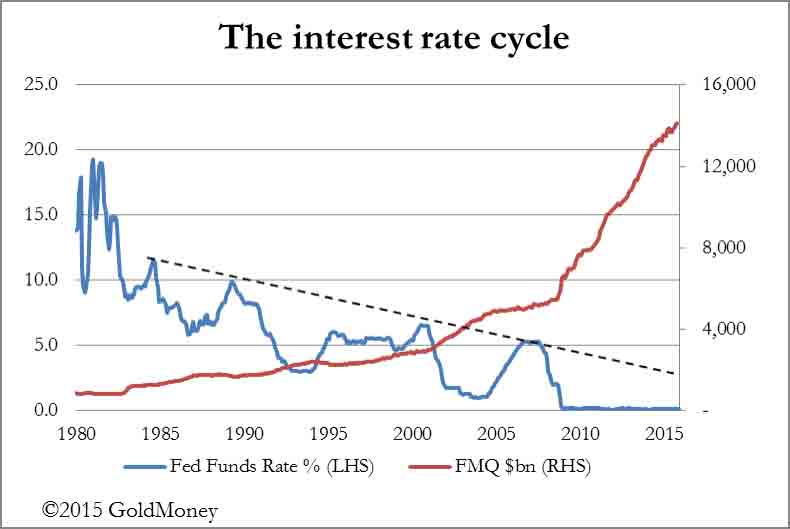

The chart below illustrates the problem. It is of the Fed Funds Rate since 1980 and the Fiat Money Quantity, which simply put is the sum of the commercial banks’ reserves at the Fed, plus cash and sight deposits held at the banks.

From the mid-eighties, successive interest rate peaks (the pecked line) have declined to the point, which if the trend continues, would indicate a Fed Funds Rate peak today of roughly 3%. It is clear that the reason for this declining trend is the increase in bank-related debt, the principal counterpart to FMQ, and the interest burden it places on borrowers.

This trend of declining interest rate peaks was established before the Lehman crisis, when the Fed’s response was to rapidly expand its balance sheet. The result is FMQ growth accelerated from a compounding annual rate of 5.8% to 14%, taking FMQ to 70% above the previous long-term trend today. It would therefore require a far smaller increase in interest rates than indicated by the pecked line to tip the monetary system into a crisis, perhaps a Fed Funds Rate of as little as 1%.

The idea that we can be so precise about interest rate levels is obviously nonsense. If the Fed increases the Fed Funds Rate even slightly, non-financial borrowers often end up paying a significantly higher rate that includes a larger interest rate spread. The spread between interbank and corporate borrowing rates becomes an important indicator of financial stress, and junk bonds are already signalling deteriorating borrowing conditions. Just the threat of higher interest rates could turn out to be destabilising for the financial sector.

A problem of the financial sector’s own making

The key metric which has permitted debt to increase at such a pace is the declining rate of price inflation. This rate has not responded to monetary inflation as one would expect, having continually fallen from the high rates of the late ‘seventies, while the quantity of money and credit has increased significantly. The reason the rate of price inflation has declined is that by taking over the securities industry in the 1980s, the banks have been able to combine their licence to create credit out of thin air with the direct application of this credit into financial instruments. The result has not only been extremely profitable for the banks, but it has diverted excess credit from less profitable non-financial activities.

This partly explains why banks have increasingly neglected commercial and retail customers, concentrating capital allocation into investment banking. The effect has been to generally confine price inflation to assets, such as stocks, bonds and property. At the same time consumers have been packaged through securitised bulk lending for mortgages, student loans, credit cards and motor loans. Any pretence that banks exist to provide a service for customers has flown out of the window.

At the same time, this credit and securities duopoly has given the banks the ability to magically create paper substitutes for physical commodities through the futures markets, suppressing prices to levels below where they would otherwise be. In turn, this has reduced the pressure on price inflation for consumer goods. The decline in price inflation over the last thirty-five years is therefore the combined result of suppressed commodity prices, the reduced expansion of credit available to non-financial sectors, as well as favourable changes in statistical methods.

vA declining trend of interest rates has been crucial for the profitable expansion of financial activities for their own sake. Since assets are valued with reference to interest rates, the falling trend in interest rates since the mid-eighties has delivered large profits to the banks and their financial customers.

The ground-level which inhibits further credit expansion is zero interest rates, a condition that has existed for seven years. Despite talk of negative rates, the impetus lower interest rates give to expansion of the financial side of the economy has already come to an end. Attempts by the Fed to raise interest rates, even slightly, should be considered in this light.

The next financial crisis could manifest itself in the coming months. The time-line of monetary expansion reflected in the chart above is at risk of being terminated by events. It so, it will mark the end of current central bank monetary policies and state control of markets, as free markets reassert realistic pricing. Government bond yields will normalise, stock markets will fall, and banks will almost certainly fail. Supressed commodity prices will rise as banks, short through paper contracts, will be forced to close their positions. Credit default swaps, where the banks are collectively exposed to losses when interest rates rise, will be a further source of grief.

When something as epochal as this happens, we can expect the macroeconomic establishment to be clueless with respect to the problem itself and its scale. Central banks will naturally revert to the Lehman remedy of further monetary expansion to cover the losses, whose enormous scale will not be apparent at the outset. This time, not only will the fiat money quantity accelerate into hyper-drive, it will be impossible to maintain the purchasing-power of the world’s reserve currency, therefore threatening that of all the others.

This month’s FOMC rate decision will not change this outlook, but it could bring forward the timing.

This 1% figure as a tipping point is close to my own – that is if those other tipping points do not click in first.

Check out what happened when the BoE raised rates by 1.25% in circa 2004.

Best wishes,

Edward