The majority of economists view deflation as a general decline in prices of goods and services. This is viewed as a major threat to the public’s well being for deflation is seen as a major factor that plunges the economy into an economic depression. Most of them are of the view that central banks and governments’ world wide must aggressively fight the possible emergence of deflation. We suggest that this way of thinking stems from an erroneous view of what deflation is. As a result it is overlooked that it is not deflation but rather monetary pumping which is the root of economic hardship.

Is inflation about price increases?

According to Mises (Human Action, p. 432), “What many people today call inflation or deflation is no longer the great increase or decline in the supply of money, but its inexorable consequences, the general tendency toward a rise or fall in commodity prices and wage rates.”

Once inflation is defined as a general rise in prices, then anything which contributes to price rises is called inflationary and therefore must be guarded against. It is no longer the central bank and fractional-reserve banking that are the sources of inflation, but rather various other causes. In this framework, not only has the central bank nothing to do with inflation, but on the contrary: the bank is regarded as an inflation fighter.

A fall in unemployment or a rise in economic activity are all seen as potential inflationary triggers and therefore must be restrained by central-bank policies. Some other triggers like rises in commodity prices or workers wages are also regarded as potential threats and therefore must be always under the watchful eye of the central bank.

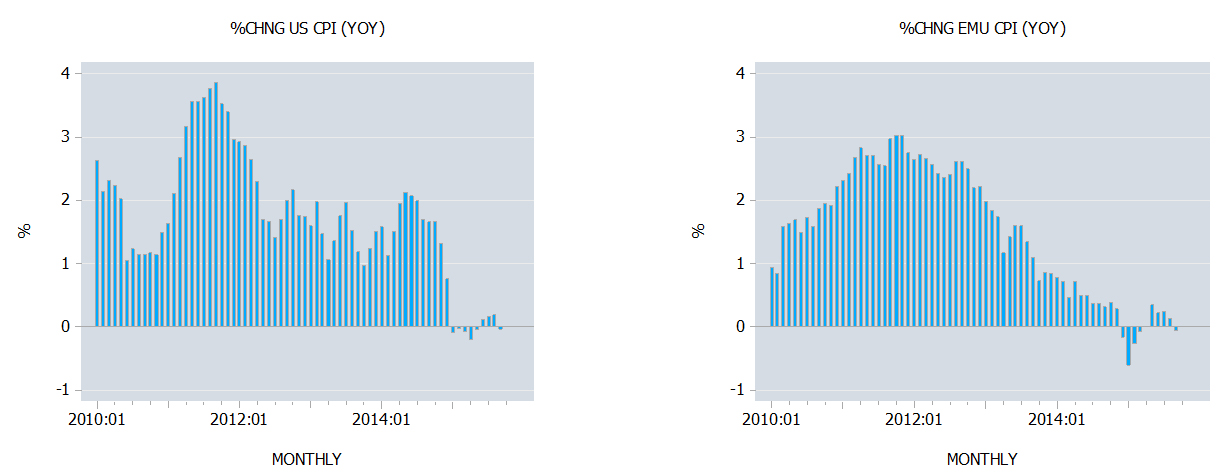

Most commentators hold that inflation is a general rise in prices that can be captured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), but they disagree about the causes of inflation.

In one camp the monetarists, argue that changes in money supply cause changes in the CPI. In the other camp, we have economists who argue that inflation is caused by various real factors. These economists are having doubts about the proposition that changes in money supply cause changes in the CPI. They believe that it is likely to be the other way around.

Contrary to the accepted view inflation is not a general rise in prices, caused either by money supply growth, or by real factors. It is simply an increase in the money stock.

Pay attention to what we are not saying. We don’t say, as monetarists do, that inflation is rises in prices caused by rises in the money supply. All that we suggest is that an increase in the money stock is what constitutes inflation.

Looking at inflation this way makes it very clear why it is bad news. When money is increased there are always first recipients of money who can buy more goods and services at still unchanged prices.

The second recipients of money also enjoy the new money. However, the successive recipients derive less benefit as prices of goods and services begin to rise. (Note that a price of a good is the amount of money paid per unit of a good).

So long as the prices of goods they sell are rising much faster than the prices of goods they buy, the successive recipients of new money still benefit.

The sufferers are those individuals who get the money last or not at all. They find that the prices of goods they buy have increased while the prices of goods and services they offer have hardly moved.

On a closer inspection we can also establish that monetary injections give rise to demand for goods and services, which is not supported by the production of goods and services. It results in the transfer of wealth from wealth generators to non-wealth generating activities, or bubble activities.

While increases in money supply (i.e. inflation) are likely to be revealed in price increases registered by the CPI, this need not always be the case. Prices are determined by real and monetary factors.

Consequently it can occur that if the real factors are pulling things in an opposite direction to monetary factors no visible change in prices might take place. Whilst money growth is buoyant i.e. inflation is high, prices might display low increases. (Remember a price is the amount of money per unit of something).

Clearly, if we were to regard inflation as rises in the CPI, we would be reaching misleading conclusions regarding the state of the economy.

On this Rothbard wrote (America’s Great Depression, p. 153), “The fact that general prices were more or less stable during the 1920’s told most economists that there was no inflationary threat, and therefore the events of the great depression caught them completely unaware.”

Is deflation the root of all the evils?

So while inflation is rises in the money stock, deflation can be seen as the opposite, which is the fall in the money stock. Or we can say that whereas monetary expansion gives rise to a bubble, the monetary contraction leads to the deflation of the bubble. It seems therefore that deflation in this sense must be preceded by inflation.

Following the views of the famous American economists Irving Fisher most economists regard deflation as bad news. Irving Fisher labelled deflation the root of almost all the evils (Irving Fisher, Booms and depressions, London: George Allen, p. 39).

We suggest that deflation is the beginning of the process of economic healing. Deflation arrests the transfer of wealth from wealth producers to various non productive bubble activities caused by the prior monetary inflation. By arresting the transfer it arrests the process of economic impoverishment. Contrary to mainstream thinking then, deflation of the money stock strengthens the producers of wealth, thereby revitalizing the economy.

On this Rothbard wrote (AGD, p. 24), “deflationary credit contraction greatly helps to speed up the adjustment process, and hence the completion of business recovery, in ways as yet unrecognized.”

Obviously the side effects that accompany monetary deflation are never pleasant. These bad side effects are not caused by deflation but rather by the previous monetary inflation. All that deflation does is to shatter the illusion of prosperity created by monetary inflation. Deflation removes various bubble activities thereby strengthening the process of wealth generation.

The popular belief that a fall in the money stock leads to general economic impoverishment emanates from a view that money can grow the economy. What however, enables economic growth is not more money but more capital goods per capita. Furthermore, economists who regard a general fall in prices as an important cause of depression overlook the fact that what matters for business is not the general behavior of prices, but the price differentials between selling prices and costs.

A general fall in prices need not be always in response to monetary deflation. For instance, for given money stock an increase in the demand for money can take place on account of a growing economy and rising living standard. This in turn will lead to a general fall in prices and hence will be labeled as deflation.

Should then this fall in prices be regarded as bad? In the market economy a fall in prices in response to an increase in real wealth is a mechanism through which wealth expansion permeates throughout the economy. With the increase in the purchasing power of money people can now secure for themselves a greater amount of goods and services.

Does money disappearance cause depression?

In his writings professor Milton Friedman blamed the central bank policies for causing the Great Depression. According to Friedman the Federal Reserve failed to pump enough reserves into the banking system to prevent the collapse in the money stock. For Friedman, the failure of the US central bank is not that it caused the monetary bubble but that it allowed the deflation of the bubble. Murray Rothbard, while agreeing with Friedman that the money stock fell sharply, found that the Federal Reserve had been aggressively pumping reserves into the banking system. Notwithstanding this pumping, the money stock continued to fall. The sharp fall in the money stock, contrary to Friedman, is not indicative of the Federal Reserve’s failure to pump the money supply. It is indicative of the shrinking pool of real wealth brought about by previous loose monetary policies of the central bank and the resulting strong increases in the money supply rate of growth.

The existence of the central bank and fractional reserve banking permits commercial banks to generate credit which is not backed up by real wealth i.e. credit out of “thin air.” Once the unbacked credit is generated it creates activities that the free market would never approve, i.e. these activities are consuming and not producing real wealth. As long as the pool of real wealth is expanding and banks are eager to expand credit various false activities continue to prosper.

Whenever the extensive creation of credit out of “thin air” lifts the pace of real-wealth consumption above the pace of real-wealth production the flow of real savings is arrested and a decline in the pool of real wealth is set in motion. The performance of various activities starts to deteriorate and bank’s bad loans start to rise. In response to this, banks begin to call back their loans and this in turn sets in motion a decline in the money stock. (Remember that here we have credit that banks have created out of “thin air”. This type of credit never had a proper owner. Once it is repaid to the bank and the bank doesn’t create new loan it must disappear. This is not the case when the loan is fully backed by real wealth – once it is repaid it goes via the bank to its original owner i.e. lender. The bank here is just an intermediary.

We can thus conclude that depression is not caused by the collapse in the money stock as such, but in response to the shrinking pool of real wealth, which also causes the disappearance of money out of “thin air.” Even if the central bank were to be successful in preventing the disappearance of money, this would not be able to prevent a depression if the pool of real wealth is declining.

Also, even if loose monetary policies were to succeed in lifting prices and inflationary expectations, this couldn’t revive the economy as long as the pool of real wealth is declining.

We can conclude that it is the loose monetary policies of the central bank and fractional reserve banking that causes a persistent misallocation of resources, which in turn weakens the flow of real savings and hence weakens the process of real wealth formation. This in turn implies that the primary causes of depression are loose monetary policies of the central bank and fractional reserve banking. A fall in prices is just a symptom as it were.

There are some well made points here but there is also some real confusion and some (universal) ignorance for which the writer cannot be blamed.

This stems from a universal level of ignorance by economists everywhere.

We are talking about base money stock and pure credit stock, (or fiat money stock).

For an economy to prosper there has to be enough liquidity – money stock in circulation and available for spending.

Hoarding of money stock goes in cycles as people save more or spend more than they earn. Other cycles occur as people import more and spend less locally or they borrow less and spend less locally and then reverse that pattern.

So we have three spending cycles, and three liquidity cycles.

Each of these cycles affects the level of liquidity but as spending slows less liquidity is needed locally. A constant total stock of money may look healthy from that viewpoint – without numbers to back it up.

In fact what we have is an imbalance between true credit and base money.

When the stock of money is low for whatever reason – population growth, greater wealth, too much savings and too little borrowing, or a downwards spiral in spending which remains a serious potential problem during spending cycles, etc. it does n necessarily mean that we need more pure credit. It does not mean that people should be forced to borrow more so as to provide more pure credit. We need the right balance.

What has happened because of a lack of creation of base money is that pure credit now provides far too much of the money stock. Rather than the ratio of credit to base money being ten times more of pure credit (fiat) than base money it might be better to have the ratio tilt towards having more base money than pure credit money in circulation. Then people do not have to be forced to borrow in order to maintain or increase liquidity. They will have more choice in aggregate.

There is also the point, well made by the writer above, that the first recipients of new money benefit at the expense of others. What was not said was that:

#1 When new base money is created everyone can be given some of it. So you provide me with some free services and I provide you with some free services. That is fair. And we now have enough stock of money.

#2 When pure credit is repaid more pure credit may be needed to keep the balance of spending in all sectors of the economy undisturbed by that.

The pure credit can also be created centrally and issued to the market. The central bank is the first recipient and it earns interest at market rates on the money created. This income can be fed back to the fiscus and so benefit the whole community. Prices of capital goods purchased will not inflate because the money is a replacement to keep spending levels steady. Those first getting the new pure credit from the central bank will not benefit in that way.

What really matters are two things:

#a That there is always enough liquidity in the economy so that people do not have to wait to be paid. Or to buy cash to spend by borrowing or paying more for it (as is reportedly happening in Zimbabwe where $1 cash reportedly costs $1.07 currently in some places)

#b Because no one ever knows how much liquidity is needed there should generally be a surplus rather than a deficit.

From those two things we must accept a variable level of inflation, not of prices as the writer correctly pointed out, but in terms of the falling value of money which as the writer said, is not the same thing. We can have both of course.

Now when new money is created it can have a stimulative effect and if it is distributed in a way which increases spending that will happen. Thus we can avoid downwards spirals without having to create a whole lot of government borrowing to be spent on special projects and trickle down.

Cur VAT and give the new money to the fiscus to replace lost revenue. Everyone has more money to spend at month end. and the more they spend the more of it they get. All sectors get a boost.

Finally we need to address the structure of the economic framework which is a whole new story. I cannot give much space to here.

Keynes tried to manage the rate o inflation without first creating a framework for pricing in the economy which would follow Adam Smith’s laws of supply and demand. Whereas

Chapter 1 page 1 paragraph 1: In his ‘A Tract on Monetary Policy’, first published by Macmillan in 1923 J, M Keynes wrote:

“If, by a change in the established standard of value [of money], a man received and owned twice as much money as he did before in payment for all rights and for all efforts, and if he also paid out twice as much money for all acquisitions and for all satisfactions, he would be wholly unaffected”

But Keynes did not address this part of the problem. All kinds of prices do not follow that rule of Adam Smith’s. If they did then this result of people hardly being affected by the falling value of money would take place. And I can show how this can be done. See below.

For example, as Keynes himself observed, fixed interest bonds repay money not value, plus interest. I add that currencies are not adjusting properly, interest rates are managed, and the cost of monthly repayments in the housing sector do not follow these rules either. We need to know how to repay value not purchasing power, and currently there is no good measure for that in the literature except in my own.

A WASTED CENTURY

Economist have wasted the best part of a century ignoring all this and instead of removing the problems they have attempted to address the consequences with interventions including in interest rates. These confuse people and their financial plans, and they re-distribute wealth too. They do not create any wealth.

If you want to know more I am writing all of this up in a book and there are also my websites starting here:

http://macr-economic-design.blogspot.com