It’s easy to criticise the Fed for its failures, because its successes have been only one in number: kicking the can down the road.

But we should spare a thought for the difficulties policy-makers now face. So what would you do if you were on the Open Markets Committee?

Repeatedly kicking that can has so far succeeded, but economic conditions are changing all the time, throwing up new challenges. The next chart dramatically exposes the one issue that historically would have determined interest rate policy in advance, but is being widely ignored, even by the FOMC.

Simply subtracting M2 money from M1 money gives a running indication of bank lending. And as the chart shows, it has been growing above trend since mid-January, followed by a sudden spurt timed from early July. This requires, on the face of it, an immediate normalisation of interest rates to bring the expansion of bank credit back towards its established trend.

The source of this increase in bank lending can be attributed in some measure to a draw-down of bank reserves held at the Fed. Controlling the release of excess reserves was always seen as the eventual challenge for the Fed, when it expanded its balance sheet in the wake of the Lehman crisis, and that moment seems to have arrived. Since March, total reserve balances have declined just $150bn, which when geared up through a modest fractional reserve multiplier, easily accounts for the spurt in bank credit. It requires an increase in the Fed Funds Rate to slow down the outflow.

The question then arises, who is borrowing this money? If other information available to the FOMC reveals a developing appetite from the non-financial sector, and which can also be taken to indicate an improvement in business conditions, then the Fed Funds Rate should be increased without delay. Credit being applied to the non-financial economy is bound to lead to higher prices, meaning that the CPI target could be exceeded much sooner than anyone thinks is likely.

It may still be too early to judge the price inflation effect of an above-trend increase in bank lending, based on the lack of response to increased amounts of money supply since the Lehman crisis. Before then, it was thought that the link was strong between changes in the money quantity and changes in the general price level, albeit with a time-lag. The Fed’s post-Lehman experience and also that of Japan and the Eurozone suggests otherwise, so the FOMC is unconcerned. Instead it is paying more attention to other matters.

The greatest threat to the US economy is likely to be external, with the Committee being forced to pay increasing attention to non-domestic issues. With both Japan and Europe struggling to avoid recession, export markets for American goods and services are fragile, and the last thing that’s needed is a monetary policy that drives the dollar higher against other currencies. Furthermore, the European banks are in a deepening crisis, which would probably become globally systemic if rising US interest rates undermined European bond markets. The reality is the Fed finds it extremely difficult to raise interest rates when the other major central banks are still reducing theirs.

Domestically, the economy appears reasonably stable, but as yet, it is too early to say the increase in bank lending is leading to an increasing rate of economic growth, except perhaps for one other key indicator, and that is LIBOR.

There has been a sharp rise in dollar LIBOR rates, which may or may not be financing growing demand. Market participants are attributing it to a one-off regulatory effect on money-market funds, driving money out of prime lending into government-oriented funds. This creates a shortage of finance for non-government entities, hence the increase in LIBOR. The effect is shown in our second chart, which is of 3-Month LIBOR.

But hold on a minute. LIBOR has been rising for the last two years, not just in recent months. If the chart was of a stock, you would see a share price heading for the moon. The assumption that it is a shortage of finance from money-market funds driving LIBOR higher has attractions, but there must be a deeper reason. Regulatory changes are only part of it.

It seems that despite the Fed’s interest rate stance, the market has been moving interest rates higher for some time. Taken together with the evidence of an increase in bank lending, it appears likely that LIBOR is reflecting an increase in genuine demand for money from the non-financial sector. All this is in sharp contrast with developments elsewhere in the world, with negative interest rates and sub-zero bond yields in Europe and Japan all failing to generate a scintilla of economic demand.

With government bond yields elsewhere diving into negative territory, there is little doubt that bond prices are discounting global interest rates not rising for a considerable time. Monetary policy has contributed to a world-wide bubble of unprecedented proportions, fuelled by risk aversion by the banks and central bank buying. Ideally, monetary policy should seek to deflate this bubble gently, without causing undue investor distress and triggering systemic problems. Addressing this issue should now be a growing priority for all the major central banks, not just the Fed.

Perhaps a modest rise in the Fed Funds Rate, in order to take the steam out of the bond market, appeals in this context, but that can only be certain to affect the short end of the yield curve. However, the likely currency effect on the dollar versus the euro of raising dollar interest rates could squeeze American exporters badly. Then there’s those pesky Chinese.

On several occasions, when the FOMC has been ready to raise the Fed Funds Rate, China has devalued the yuan by enough to undermine the Fed’s economic predictions. She has clearly signalled that she does not want rising dollar interest rates. Furthermore, if the Fed was to raise rates, the losses on China’s portfolio of US Treasuries could be immense, and it is not known how she might respond.

Also, not only are the known knowns conducive to inaction, but as Donald Rumsfeld famously had it, there are the unknown knowns and unknown unknowns leading to policy paralysis as well. The solution for central planners probably lies not with monetary policy, which has clearly run its course, but with fiscal policy. The US Government is increasingly being encouraged to take advantage of ultra-low bond yields to initiate an infrastructure development programme, following the precedent of the New Deal in the 1930s. That might satisfy portfolio demand from the pension funds and insurance companies for long-dated bonds, and at the same time would be expected to underwrite future economic growth, allowing an eventual return to interest rate normality.

President Trump would probably do it, and so would President Hillary, but they will not be in office until 20th January next year. All things considered, perhaps it’s time for yet more inaction and to hope for the best. Only, that is, so long as banks don’t draw down their reserves at the Fed to profit from higher LIBOR, and LIBOR normalises after the October regulatory deadline.

Taking a step back…

We have just described the surreal world in which FOMC members now find themselves. It is abundantly obvious that the entire central banking community has lost its way, and is clueless as to where it has all gone wrong. The fault, as they see it is not with monetary policy, but lies in the unpredictability of free markets. Like kids from Brooklyn lost in the Amazon jungle, they are in unfamiliar territory, imagining anacondas and jaguars behind every tree.

The FOMC released its minutes for the July meeting last night (Wednesday). A word-search reveals no mention of M2, M1, or LIBOR. The only reference to bank lending was in connection with a loan officer opinion survey. It appears the FOMC is either incompetent in missing the connection between an increase in bank lending and an increase in LIBOR, or chose to keep quiet about it.

Ever since Paul Volcker wrested control of interest rates from the market in 1981, Fed policy alone, and not the availability of savings, has set interest rates. Having taken full control of interest rates and deregulated the banks, the consequence has been excessive growth of dollar-denominated debt, requiring lower and lower interest rates in order for accumulating debt to be serviced without default. And where the Fed has gone, in the name of currency stability other central banks have also ventured.

It is hardly surprising that with what amounts to the elimination of the role of genuine savings as the principal stabilising factor in the economy, monetary policy since Volcker’s action has finally led us to the logical conclusion of zero interest rates. And here is the problem: there can be no increase in interest rates from this end-point without triggering a credit crisis. The rise in LIBOR better be temporary, or else.

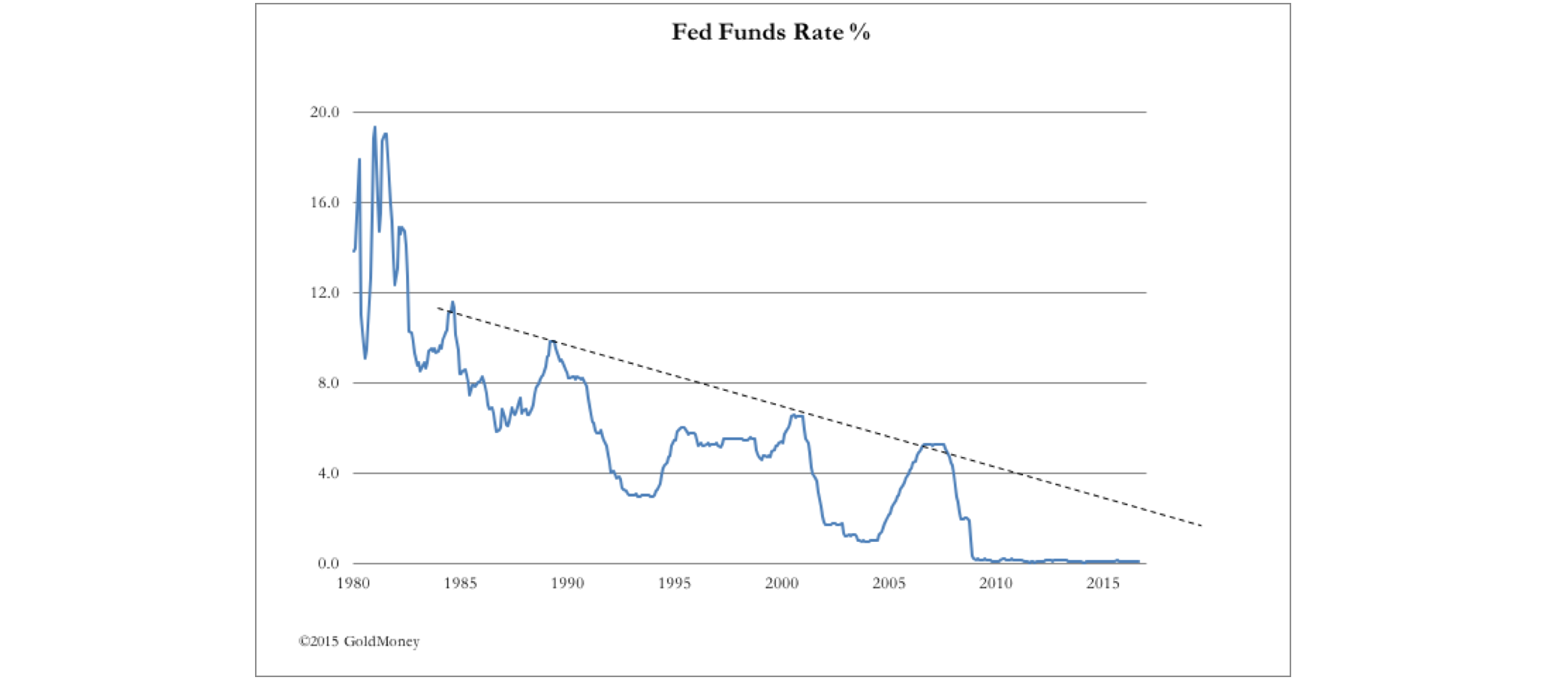

This is confirmed by a descending interest rate ceiling from the 1980s, that marks lower and lower rate peaks required to trigger widespread bankruptcies, and we are getting close to it. Such a scenario is illustrated in our last chart, which confirms this danger.

The dotted line links interest rate peaks that in the past triggered slumps in business activity and threatened waves of bankruptcies on successive credit cycles. The pace of its decline is a reflection of the total accumulation of private sector debt, and any attempt to raise rates close to the dotted line will almost certainly be enough to trigger a new credit crisis. As of now, a Fed Funds Rate of not much more that 2% will be enough to collapse the economy. The private sector’s debt burden is simply too large for it to be sustained with money-market rates much higher than that.

That declining trend line hangs over us like the sword of Damocles. We are waiting for the next credit crisis to be triggered, and 3-Month LIBOR rates appear to be taking us in that direction. The one-year rate, at 1.5% is even closer. There can be little doubt that the world of dollars is far more precarious than the Fed realises or would admit. Yet given the growth in bank lending shown in the first chart, the Fed should raise interest rates, significantly and soon. On the balance of probabilities, they will shy away from raising rates to the level required to subdue future price inflation, though smaller, insufficient rises are likely when the FOMC wakes up to the inflationary danger.

The similarity with the way conditions developed in the 1970s, the decade of stagflation, is remarkable. Interest rates rose over the course of that decade, but never enough to persuade people to hold on to their money rather than spend it before it bought less. When people know prices are rising, they reduce their preference for holding money en masse, pushing prices up even more. Economists find that something is happening which in their book shouldn’t: price inflation accelerates despite rising unemployment.

The scale of each succeeding credit crisis is increasing as well, most noticeably from the dot-com boom onwards. The Greenspan put rescued us from that one. The Lehman crisis that followed was magnitudes larger than the bursting of the dot-com bubble, so the Bernanke put was larger than Greenspan’s. How big will the Yellen put have to be? It is clear that accelerating debt levels, far from being a solve-all solution in the past, have themselves become the problem.

This week is the forty-fifth anniversary of the end of the Bretton Woods agreement, when in August 1971 President Nixon refused to accept dollar redemptions for gold. It is no coincidence that price inflation increased alarmingly over the rest of that decade, and that the gold price rose from $43 to over $800. The reason the gold price rose so strongly was the Fed chose to keep interest rates lower than required to maintain the dollar’s purchasing power. And that is where we appear to be today.

The betting must be that the Fed will once again be reluctant to protect the purchasing power of the dollar, for all the reasons stated in this article. Indeed, an inflation target of 2% confirms the direction of their thinking in this matter. When the CPI is rising by over 4% annually, does anyone think the Fed will raise rates enough to stop the CPI rising any faster?

The Fed’s primary mission is to kick that can down the road, not to protect the dollar. It will only be as a belated response to price inflation getting out of control, that the FOMC will be forced to raise interest rates. Always too little, too late.

So what would you do if you were on the Open Markets Committee?

Resign!