“Sir,

“Most of the commentary in the UK press since the announcement of the “merger” of Standard Life with Aberdeen has focused on job losses in the City or the degree of power each set of shareholders might have. What about the most important people affected by this deal, the investors whose money both manage?

“Little” Aberdeen is well known for its dominance in Asian markets, but it already has a reputation for being too large to manoeuvre. This is widely believed to be one of the factors in the withering of its performance in recent years and other managers have frequently gained by avoiding stocks dominated by the behemoth funds. Now it is to add yet more firepower, controlled by fewer minds in concentrated groupthink. How can this improve performance? And what of client servicing? If your fund manager has £600bn under management, how large does your own personal portfolio need to be for the company to care if you are displeased with them in some way?

“The City agonises about how it might restore ethical behaviour to its participants. Well, here is a suggestion: block this merger and make all future ones consider the impact on fund performance across the majority of accounts by client numbers (not assets under management, which favours just a few sovereign wealth funds).

“The money we manage is people’s hopes and dreams. We seem to have forgotten this. If we keep allowing mergers to create groups so large that they are unable to perform and simply dismiss their real owners, we can only dash those hopes and trample on those dreams.”

- Letter to the Financial Times from Sally Macdonald, Stevington, Bedfordshire, UK, 18 March 2017.

Another letter to the Financial Times this weekend also makes for interesting reading. A correspondent “looking for suitable funds to invest in” asks Lucy Warwick-Ching in FT Money whether there is a league table for the total charges levied on “all the leading general managed funds”. Assessing genuinely comparable funds on the basis of their fees is entirely legitimate, but ranking disparate funds primarily on the basis of cost is altogether more questionable.

The question is more than usually pertinent given a) the vulnerable (a.k.a. elevated) nature of developed world stock markets (with the honourable exception of Japan) and b) the Niagara of money flooding into those markets by way of low cost exchange-traded funds, or ETFs.

In his latest flow of funds analysis, Ed Yardeni asks whether

“We may be witnessing the beginning of an ETF-led melt-up, which may simply reflect individual investors pouring money into passive stock index funds. Lots of them seem to be more interested in seeking out low-cost funds rather than cheap stocks. In this case, valuation multiples would lead the melt-up, until something happens to scare investors out of those passive funds, which could trigger either a correction or a nasty meltdown. It is obviously a bit late in the game to start only now to be a long-term investor given that stocks aren’t cheap no matter how valuation is sliced and diced.”

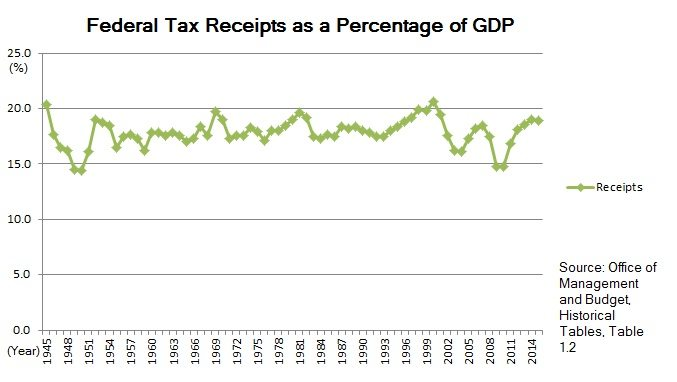

The extent of those inflows can be seen in the chart below.

At the risk of labouring the point, US stocks are not just not cheap, but almost unprecedentedly expensive, as assessed using Robert Shiller’s CAPE ratio:

Shiller Cyclically Adjusted P/E ratio for the S&P 500, 1880-2016

Source: http://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe/

To reiterate, the US stock market currently trades at around the same level as at the dawn of the Great Crash of 1929. Its current Shiller p/e of over 29 compares to a long run average of 16.7 times. On a crude comparative basis this implies an overvaluation relative to the long run average of roughly 75%. (This analysis invariably sucks in bullish apologists for what seems to be an obviously expensive market. We have no dog in the fight since we’re not short US stocks and merely prefer to seek a margin of safety in more defensive stocks and funds elsewhere. Currently, Asia fits the bill perfectly.) The UK stock market has also reached a record high despite a deteriorating outlook for political and trade stability in Europe.

We would suggest, probably like most investment managers, that the single most important decision that can be made in the context of long term portfolio management is how to allocate capital across the various asset classes. But Lucy Warwick-Ching’s reader, and the visible recent success of ETF firms at attracting capital inflows, seems to indicate that a sizeable cohort of current investors is putting the cart of low fees before the horse of discrimination in prudent asset allocation. This has all the signs of being penny wise and pound (and dollar) foolish.

As the managers at Giverny Capital point out, the problem with passive management is that for many of its followers, it is not really passive at all. The average turnover rate of exchange traded funds held by investors is 880% per year. (Source: Financial Times: Jack Bogle: the lessons we must take from ETFs (December 11, 2016.)) In other words, average “passive” investors hold their ETFs for about 47 days. The average holding period for the SPY index fund, which tracks the S&P 500, is roughly 12 days, equivalent to an annual turnover rate of around 3,000%. As Giverny indicate,

“High turnover leads to lower returns (the second principle of thermodynamics applied to the stock market). For example, the SPY index fund has achieved an annual return of 6.9% over the last decade. Yet the holders of this fund, as a whole, only achieved an annual return of 3.5%. Half of the return has literally “evaporated” into transactional activities.. there are now more than 6,000 different ETFs compared to 1,000 a decade ago. [As Wall Street would no doubt affirm, if the ducks are quacking, feed them.] The large amount of choice and ease of transaction inherent to ETFs make their owners even more irrational.

“In short, whether it is “robots” or passive funds, the problem is not the financial product but rather the self-destructive behaviour of investors. By their impatience and willy-nilly behaviour, investors are often paradoxically the cause of their own underperformance.”

Solutions ?

- Look beyond the US and UK stock markets for genuine value.

- Don’t overtrade.

- Beware the allure of low fees in an environment of generalised overvaluation.

To paraphrase Benjamin Franklin, the bitterness of poor returns remains long after the sweetness of low fees is forgotten. Some things in the investment world are worth paying for.