Caesar: What sayest thou to me now? Speak once again.

Soothsayer: Beware the ides of March.

Caesar: He is a dreamer; let us leave him: pass.

This famous advice, according to Shakespeare, was ignored with fatal consequences for Julius Caesar. Markets may be being similarly complacent ahead of this anniversary date next week. The Fed has signalled that it will raise interest rates at the FOMC’s March meeting, timed for the same day. It so happens that this fateful date coincides with the end of the suspension of the US debt ceiling. Dare Janet Yellen raise rates at such a sensitive juncture?

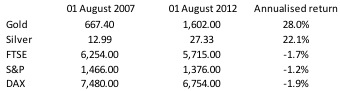

We shall see. But it is worth pointing out that gold rose strongly following the last two rate rises. It is likely that it was a “sell the rumour, buy the fact” response, and was also impelled by being the other side of the dollar trade. And the last time debt brinkmanship came up was with an agreement between the President and congress to suspend the debt ceiling in end-July 2011, following which gold rose $200 in the ensuing weeks.

As all the investment brochures say, past performance is not a guide for the future. But if the Fed raises the Fed funds rate this month by ¼%, there could be a third relief rally for gold. If the increase is more than that, which it should be to begin the process of normalising rates, gold would probably be marked down heavily. However, given the fragility of the Eurozone and the President’s desire to see a lower dollar, a half per cent raise would be a very aggressive move.

There is just a possibility that the Fed will delay for another month until the uncertainty over the budget deficit and debt ceiling is hopefully resolved, with the Eurozone an added factor. By the way, the Dutch parliamentary election is also scheduled for 15th March. If the Fed funds rate is increased, and Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom does well, the euro/dollar rate could challenge parity, heightening fears of price inflation in the Eurozone, which has already breached the ECB’s 2% target. The ECB might in turn be forced to abandon its negative interest rate policy, so perhaps Janet should wait.

The problem with the ECB reversing its monetary policy is it is the only buyer of large swathes of Eurozone sovereign debt, which otherwise are arguably distressed. The whole Eurozone market for sovereign debt is priced on the back of the ECB’s monthly purchases, and prices can be expected to fall significantly if it slashes its bond-buying programme, or is forced into abandoning negative interest rates. The ECB’s monetary policy, designed to drive the Eurozone into the sunny uplands of economic nirvana, is the sickest joke of monetary failure today, but at least it has staved off a systemic crisis, likely to undermine the entire Western banking system. Staved off, made potentially more severe, but not prevented.

Easy-money complacency is not restricted to the Eurozone. For all major central banks, rising borrowing costs are the greatest challenge today, which could be why they are talking hopefully about interest rates being at a permanently low level. It is a hope born out of the realisation that a rise in interest rates has become the primary systemic threat to economies overburdened with debt, and to those governments which have used the opportunity from suppressed interest rates to increase their indebtedness. It is also a threat to the survival of highly-geared central banks themselves, because their own balance sheets are stuffed full of over-valued bonds, certain to fall in price as rising interest rates take hold. On this subject, the Fed is geared to its own balance sheet 112 times its capital.

Debt is the Fed’s basic problem, and it doesn’t know how high rates can go without triggering a financial crisis. And even if the Fed could make an assessment for America, there is the knock-on effect of the Fed’s interest rate policy on foreign dollar borrowers, as well as on the Eurozone and Japan. China has indirectly added to the West’s problems by being the largest component of global economic growth. Her massive credit expansion is contributing to higher interest rates elsewhere by financing imports, commodity stockpiles and driving up prices. It is the lack of ability of the ECB and the Fed to raise interest rates sufficiently to counter higher rates of price inflation that’s becoming the most pressing challenge.

The hope that we are in an era of permanently low interest rates allows no headroom for President Trump’s economic plans. While he has been fighting the deep state over Russia and wire-taps, we hear not nearly enough about his plans to make America great again. Could it be because his own economists are telling him his tax cuts and infrastructure regeneration promises are more difficult to apply than first thought, at least in terms of budget control? So far, he has said he will increase defence spending by $54bn, to be paid for by cutting environmental and other domestic spending, as well as foreign aid. But apart from general statements while electioneering, that he will cut government waste, regulation and taxes, we have heard little more, other than entitlement programmes are unlikely to be affected.

In any event, from last Monday, the process of Congress negotiating the budget with the White House began. The White House budget office is drafting an official request for budgets in the 2018 fiscal year to be submitted to Congress. That still leaves us with the rest of fiscal 2017.

There appears to be a complacent assumption that with Republicans controlling Congress, Trump’s plans, after some back and forth, will be nodded through. Therefore, the assumption goes, a request for a rise in the debt ceiling might not meet insurmountable objections, unlike President Obama’s problems in 2011. That said, the suspension of the budget limit ends on 15th March and if the suspension is not to become semi-permanent, a new limit must be agreed.

Currently, the accumulated deficit stands at a fraction under $20 trillion, an emotive figure. Worryingly, at this stage of the credit cycle the budget should be balanced, or at least moving towards it. Instead, the Trump administration will probably need to issue nearly one trillion of Treasury debt for the rest of calendar 2017 on current spending projections. The White House will argue that the reduction in government spending and the pick-up in the economy will take the budget back into balance between fiscal 2018 and 2019. All that’s needed is some extra bridging finance until then.

This argument is probably unrealistic. Trump wishes to stimulate the American economy at or close to the top of the credit cycle. The intention is good, reducing the state’s share of the economy, along with the tax burden on the productive private sector. That way leads to genuine wealth creation. But it requires the government to deliver a dramatic reduction in its costs, concurrently with tax cuts and any state-financed infrastructure spending. To achieve both at the same time is as difficult as getting a democratically-elected Mexican government to imprison its own citizens by taxing them to build a wall.

Given Trump’s economic plan requires at the very least a continuance of the current rate of government borrowing, it hinges on whether the banks are prepared to increase their investment in Treasuries, at a time of rising interest rates. The excess reserves are available for the banks to extend the necessary credit, but they have already been extending increased levels of bank credit to the private sector throughout 2016. Given the US economy is at a late stage in the credit cycle, both private and government sectors are competing for funds. This is the path to accelerating price inflation, and yet higher interest rates.

If funding is short-term and gives the banks a reasonable spread above the Fed funds rate on their excess reserves, of course, bank credit will be expanded to accommodate the government. However, when the Fed raises interest rates, the interest demanded by commercial banks on buying T-bills and Treasuries will also rise, forcing bond prices down over the maturity spectrum.

So much for the hope that interest rates will remain permanently low. Future expansion of bank credit coincides with escalating demand for energy and industrial commodities from China, giving an underlying drive to global price inflation. Even if the Fed manages to finesse the transition to rising interest rates without a systemic crisis being triggered, it is unlikely the ECB will be as lucky. Also, Japan’s NIRP must come to an end, as she is directly affected by China’s economic prospects, being integral to her supply chain. Presumably, both the ECB and the BoJ will attempt to cautiously raise interest rates from NIRP through ZIRP, while nursing insolvent banks, and in the former case, governments as well.

So dire has the situation in the Eurozone become, that it could easily face a financial crisis just through the passage of time, without the ECB increasing interest rates at all. The politics are nudging events in that direction. The irony is the Chinese and Russian banking systems are the best placed to survive a financial and systemic crisis originating in the Eurozone or the US, through relatively low counterparty exposure. But then that was likely to have been the strategic intention from the outset, a point completely missed by western commentators who assume that systemic risks are most likely to emanate from China.

Before Trump was elected, the Western financial system already faced a combination of threats from rising price inflation, rising nominal interest rates and unproductive debt. His plans will only make the situation worse. The realisation that this is so, and that it is fruitless to think Trump can implement his plans when the government is already insolvent, will begin to dawn on capital markets sooner or later. Perhaps the ides of March will mark the beginning of that process. The gold price could fulfil the roll of the soothsayer, not ahead of the fateful day, but afterwards.