- The challenge to low-cost manufacturing in emerging markets is from technology

- Some industries will benefit but many jobs will be displaced globally

- The mercantilist model of emerging market growth will need to adapt

- Technology will solve some of the demographic challenges of the developed world

In July 2016 the International Labor Organisation (ILO) released a report entitled – ASEAN in Transformation – in the preface it relates the apocryphal story of a 1950’s conversation between Henry Ford, Chairman of Ford Motor Company, and Walter Reuther, Leader of the United Automobile Workers Union.

Ford asked, “Walter, how are you going to get those robots to pay your union dues?” to which Reuther responded, “Henry, how are you going to get them to buy your cars?” It reminds us that disruptive technology is not new. As the latest wave of innovation begins to disrupt employment globally, it makes sense to reassess the prospects for some of the world’s fastest growing economies.

The ILO report goes on to focus on the impact of technology on ASEAN countries, a region with 632mln people. This is an under-researched topic. They highlight the industries which are most likely to be affected and suggest ways countries can adapt to minimise the impact of automation on employment. This is their conclusion:-

Considerable opportunities for growth exist within ASEAN. Importantly, the local domestic market is expanding, and ASEAN’s middle class is expected to grow to 125 million by 2025. This represents a massive and emerging regional market.

However, threats remain, and in some cases, are intensifying. In particular, a range of labour-intensive sectors in a number of less developed countries are susceptible to major technological disruption, leading to potential large-scale job displacement. The consequences for these countries could be profoundly negative if they are unprepared to adapt.

We are witnessing the emergence of new markets, the potential relocation of production, the rise of new hiring trends and the displacement of lower skilled jobs. Supplying workers with the appropriate skills and competencies remains a major challenge. Overall, concerted efforts are required from all ASEAN stakeholders. They should act now to build a future of innovation and growth shaped with better employment opportunities.

The World Bank Development Report 2016 – Digital Dividends provides a global perspective. Here are a couple of graphs which illuminate the challenging landscape:-

Source: World Bank

If the unadjusted percentages indicated in the graph above are realised the social and political stability of many countries maybe undermined, however, the next graph shows which occupations are likely to be most at risk. It also shows which occupations can be expected to benefit from the productivity enhancing impact of new technology:-

Source: World Bank

Educational challenge

Be an expensive complement (stats knowhow) to something that’s getting cheaper (data).

—Hal Varian, Chief Economist, Google, 2014

Going back to the ILO report, the key to creating workers with the correct skills is designing appropriate education. According to Asian Nation:-

50.5% Asians, age 25 and older, who have a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education. Asians have the highest proportion of college graduates of any race or ethnic group in the country and this compares with 28 percent for all Americans 25 and older.

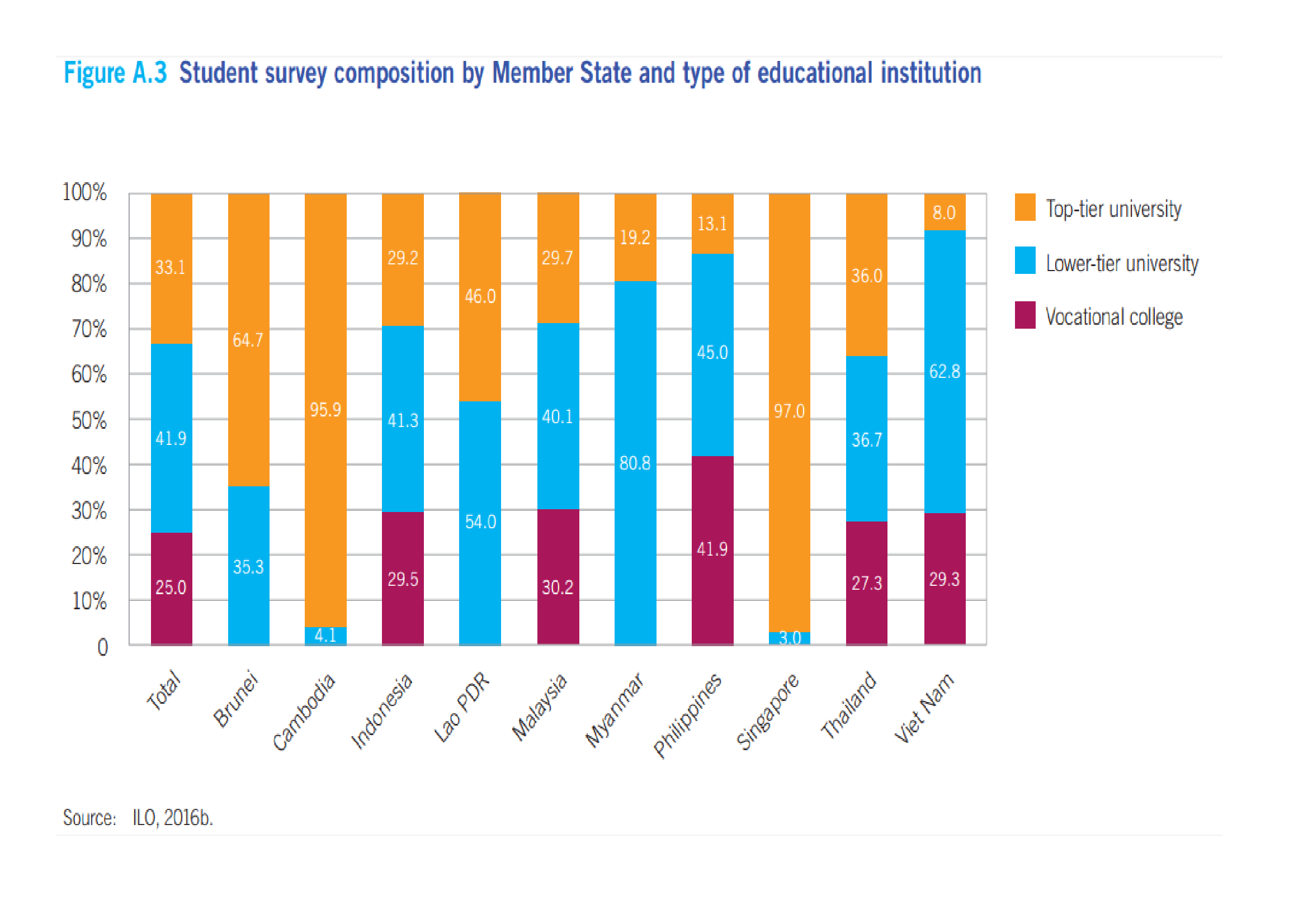

This graph shows the educational attainment across ASEAN:-

Source: ILO

Singapore scores highly but so does Cambodia, however, it is the low skilled worker who will suffer; the retraining challenges, for Asia and elsewhere, will be substantial. More than 60% of salaried workers in Indonesia and 73% in Thailand are at risk from automation. The highest risk group are employed in Textiles, Clothing and Footware. More than 9mln people are employed in this sector across ASEAN and the ILO estimate that 64% are at risk in Indonesia, 86% in Vietnam whilst in Cambodia that figure rises to 88%.

Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) is another industry which is ripe for automation. There is a heavy concentration of BPO in the Philippines where more than 1mln salaried working are employed. The ILO estimate that 89% are at risk from automation.

Earlier this year I discussed the demise of China as a low-cost manufacturing hub in – Low cost manufacturing in Asia – The Mighty Five – MITI V – Malaysia, India, Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam. I concluded:-

Vietnamese stocks look attractive, the country has the highest level of FDI of the group (6.1% of GDP) but there is a favourable case for investing in the stocks of the other members of the MITI V, even with FDI nearer 3%. They all have favourable demographics, except perhaps Thailand, and its age dependency ratio is quite low. High literacy, above 90% in all except India, should also be advantageous.

Over the next few years I remain confident about these economies but the headwinds of technology will blow through these markets, nonetheless. Low cost manufacturing has to be set alongside, efficient inventory management and transit costs. In the apparel industry, where trends change in a rapid and unpredictable fashion, the advantage of fast design to production lead times makes the benefits of robotic production, geographically close to the consumer, much more alluring.

In a fascinating post on LinkedIn – Robots Take Over – The Apparel Production – Susanna Koelblin – discusses the decision by Adidas to transfer a part of the production of their sports shoes back to Germany for the first time in more than 20 years. Another “Speed factory” will open in the US later this year. Here are some of her observations:-

It took 50 years for the world to install the first million industrial robots. The next million will take only eight. Importantly, much of the recent growth happened in particular in China, which has an aging population and where wages have risen…

German robot maker Kuka, acquired last year by China’s Midea, estimates a typical industrial robot costs about 5 euros an hour. Manufacturers spend 50 euros an hour to employ someone in Germany and about 10 euros an hour in China. Rather than seek out an even cheaper source of labor elsewhere – in another emerging Asian economy, say – Chinese manufacturers are choosing to install more robots, especially for more complex tasks. China isn’t getting rid of the work, just the workers…

It is in fact China which is leading the world in terms of the installation of industrial robots, but relative to the size of its workforce these concentrations are still relatively low. China boasts 4.9 robots/1,000 workers while Germany tops the world ranking at 30.1/1,000. That is almost twice the concentration of the US and four times that of the UK.

The current level of earnings in manufacturing still favours the work force of the MITI V but as the cost of automation continues to fall and average earnings in, lower cost Asia, rises, an inflection point will be reached:-

Source: Trading Economics

Manufacturing wage inflation has been high in Indonesia partly in response to earlier currency depreciations – over 10 years the Rupiah has declined by 46% against the US$ whilst manufacturing wages have increased by 164%. All these emerging economies maintain a manufacturing cost advantage relative to robotic automation, however, for countries like Malaysia, which has seen its currency decline by 46.7% over the last five years, whilst manufacturing wages have only risen by 37.6%, the competitive advantage versus robotic automation is narrowing. Malaysia now has a manufacturing wage cost which is slightly higher than China’s.

Interestingly, India has seen a real-terms improvement in export competitiveness. Its currency has fallen 21.4% over five years but manufacturing wages have only risen by 14.6%. Vietnam and Thailand have seen export competitiveness decline, yet in both cases they have had considerable room for manoeuvre.

I am in agreement with Dr. Jing Bing Zhang, Research Director of IDC Worldwide Robotics, we should not be worried about automation derailing the emerging market growth model over the next decade. This is what he said in a recent interview with the Diplomat:-

There are different schools of thought… From my research, I don’t see it. Maybe we will be less dependent on human labor. But there is no way this will eliminate the need for people in the next 15-20 years. We are entering high speed growth for robotics but in 2014 global density for robotics was still very low at 66 per 10,000 employees, 36 in China, 57 in Thailand, and close to none in India.

The uptake of robots does not appear to have damaged employment in Germany where unemployment recently dipped below 4%, the lowest level since 1981. One can argue that demographic forces are at work here but Germany has the highest concentration of robots relative to workers globally.

Chatham House – Robots and pensioners to the rescue – examines a different aspect of automation and demographics, focussing on Japan:-

Bleak demographics saddle Japan with a potential growth rate of less than 1 per cent, economists say, unless there are aggressive moves to accept more immigrants, boost the role of women in the workforce and overhaul workplace inefficiencies to increase productivity.

Yet despite its real and chronic problems, Japan may arguably be faring better than the image often projected of a country on the brink of an abyss. Japan still feels safe, prosperous and dazzlingly futuristic. While the overall economy has stagnated, GDP per head has outperformed most of the developed world, including Germany and France, according to World Bank figures − partly a consequence of the population crunch…

Most importantly, a shrinking population fosters innovation to boost productivity. Writing in the Financial Times, Michael Lind, a senior fellow at New America, a Washington think-tank, argued that a labour shortage can be a blessing rather than a curse: ‘Where labour is scarce and expensive, businesses have an incentive to invest in labour-saving technology,’ he wrote, ‘which boosts productivity growth by enabling fewer workers to produce more.’

That is precisely what is happening in today’s Japan, with investment pouring into robotics, industrial automation and artificial intelligence. Furuta notes that a similar phenomenon took place in 18th-century Japan, under the Tokugawa shoguns, when sharp population declines due to famine and natural disaster spurred an age of innovation in science, the arts and agriculture. Such thinking has prompted Prime Minister Abe to embrace the idea that Japan’s population crunch may have a silver lining: ‘Japan may be losing its population. But these are incentives,’ Abe said in a speech last year. ‘Japan’s demography, paradoxically, is not an onus, but a bonus.’

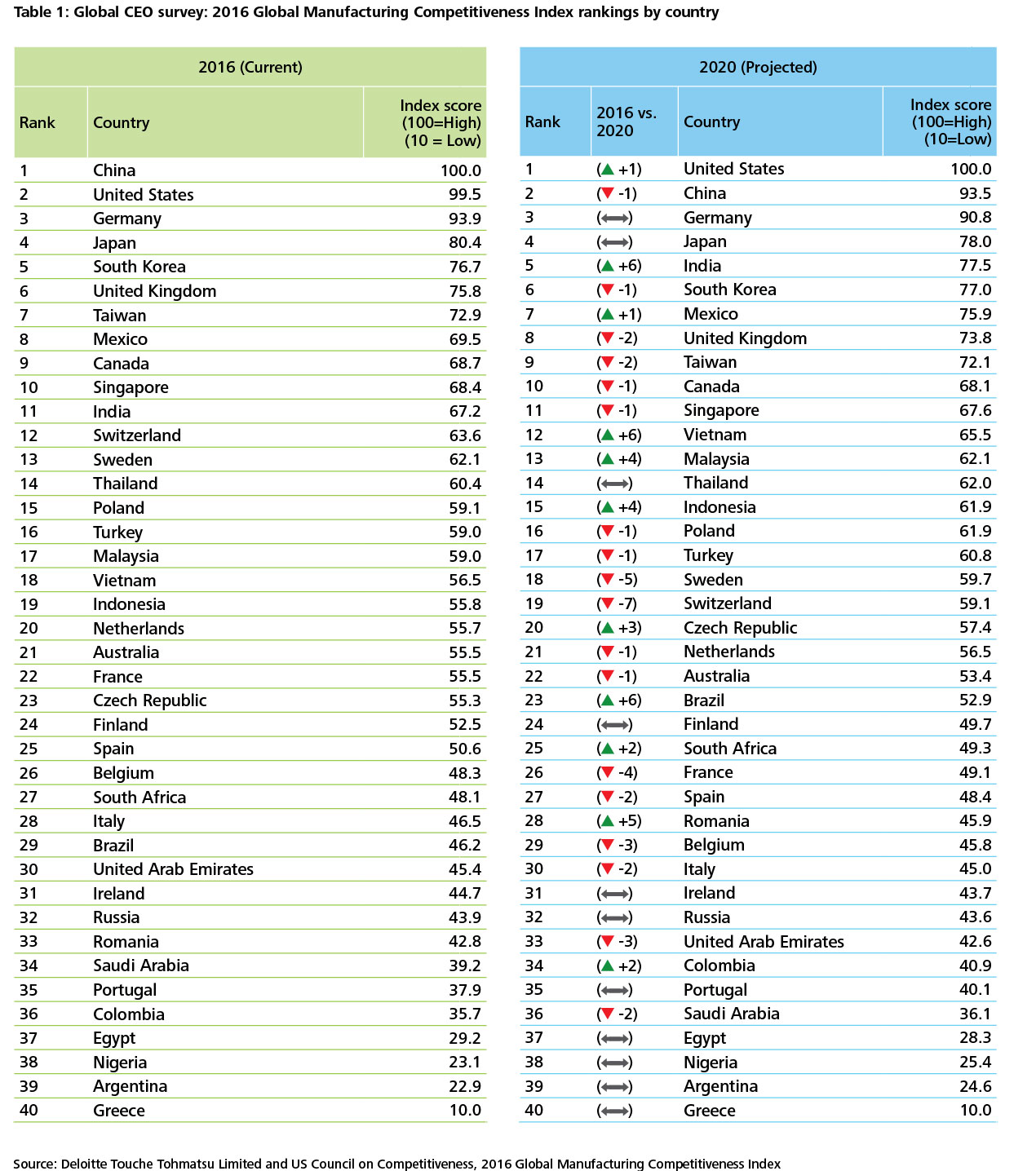

In my previous Macro Letter – No 72 – Low cost manufacturing in Asia – The Mighty Five – MITI V – I reproduced the latest Deloitte Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index, here it is again:-

Source: Deloitte

The MITI V are all expected to rise up the competitiveness ranking over the next three years – with the exception of Thailand which remains unchanged in 14th place.

I remain optimistic about emerging market growth, but keep in mind the industries which will benefit from technology and those which will be harmed. For example, the software developers of India look well placed to thrive; the garment workers of China may not.