- A corporate tax cut from 35% to 15% will cost US$200bln/annum

- A Border Adjustment Tax could raise US$100bln/annum

- The boost to GDP growth is unlikely to generate sufficient tax receipts to bridge the gap

- Without fiscal austerity, total US debt is likely to rise under Trump as it did under Reagan

“Our country needs a good ‘shutdown’ in September to fix mess!”

Donald J. Trump

The current US debt ceiling is set at $19.8trln. Debt levels are already close to that level and special accounting measures have already been implemented by the US Treasury. This year alone total federal expenditures will be $3.7trln – leaving a tax shortfall of $559bln. Meanwhile, last week, Treasury Secretary, Mnuchin announced the long awaited tax cut plan. It included a proposal to reduce the US corporate tax rate to 15% from the current level of 35%. This, it is estimated by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, will increase the government deficit by $5.5trln over the next decade.

The Trump administrations other spending plans remain on the agenda, including $1trln for infrastructure, $54bln for the military and – assuming the Mexican’s can’t pay and won’t pay – $10bln for the Southern Border Wall.

How can this possibly add up? Through spending cuts, is the simple answer. Cuts have already been made to the budget for the Environmental Protection Agency, Inland Revenue Service and Department of Education but around 65% of government expenditure, in areas such as welfare and healthcare, have been ring-fenced – they will remain off-limits. Balancing the books is going to be an awesome conjuring trick.

Even by the more conservative estimates of the Tax Foundation, the proposed tax cut will cost $2.2trln over the next 10 years. They estimate economic growth would increase by 0.4% as a result of the tax reduction, but point out that +0.9% annual GDP growth is required to offset the estimated decline in tax revenues. The sums do not appear to balance.

The chart below looks at US investment as a percentage of GDP going back to 1950, the era of Reaganomics (1981-1989) when the last substantial tax cuts occurred, suggests that the positive impact of tax reduction on economic growth, if Art Laffer is correct, may be, to borrow a phrase from Milton Friedman, long and variable:-

Source: The Economist, BEA

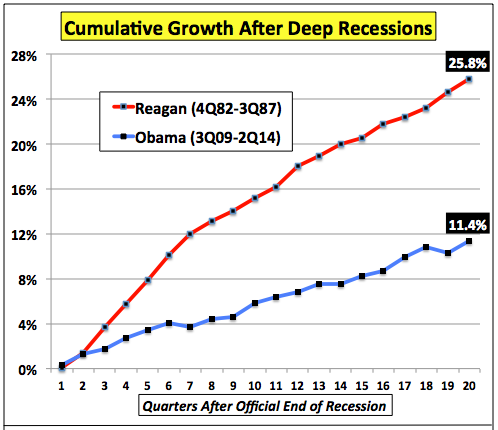

The Cato Institute – Lessons from the Reagan Tax Cuts which was published at this week, makes a number of observations (see below) but this chart, showing the GDP growth in the Reagan and Obama recessions, is instructive:-

Source: Cato Institute

One may argue that the Reagan period was an era of much higher inflation and therefore dispute the real-GDP growth differential, but the Cato Institute produce further evidence to support their argument, that tax cuts boost economic growth. Here are some of the highlights:-

Lesson #1: Lower Tax Rates Can Boost Growth

We can draw some conclusions by looking at how low-tax economies such as Singapore and Hong Kong outperform the United States. Or we can compare growth in the United States with the economic stagnation in high-tax Europe.

Source: Maddison, Cato

We can also compare growth during the Reagan years with the economic malaise of the 1970s.

Moreover, there’s lots of academic evidence showing that lower tax rates lead to better economic performance

The bottom line is that people respond to incentives. When tax rates climb, there’s more “deadweight loss” in the economy. So when tax rates fall, output increases.

Lesson #2: Some Tax Cuts “Pay for Themselves”

The key insight of the Laffer Curve is not that tax cuts are self-financing. Instead, the lesson is simply that certain tax cuts (i.e., lower marginal rates on productive behavior) lead to more economic activity. Which is another way of saying that certain tax cuts lead to more taxable income.

Source: Cato

It’s then an empirical issue to assess the level of revenue feedback.

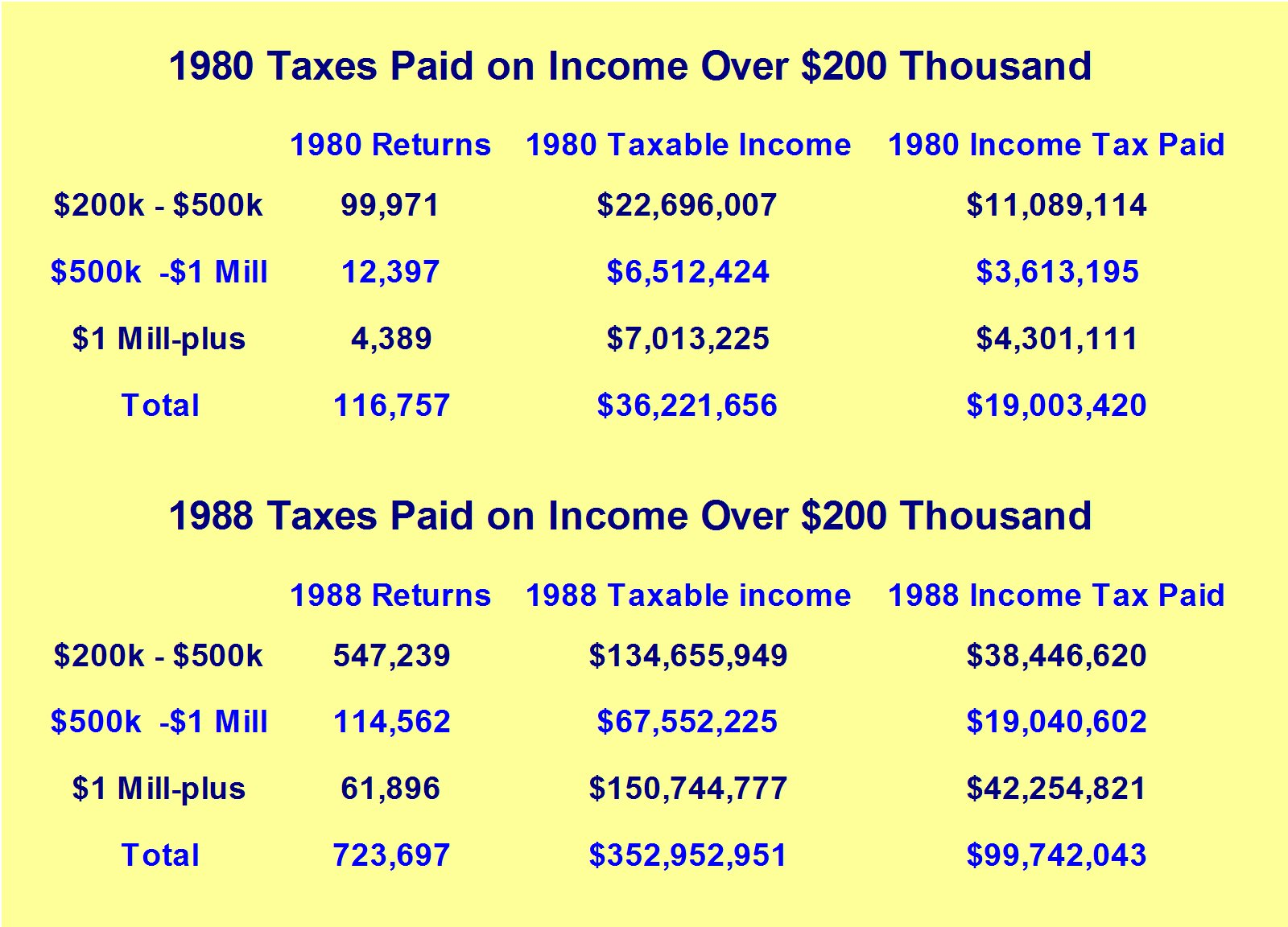

In the vast majority of the cases, the revenue feedback caused by more taxable income isn’t enough to offset the revenue loss associated with lower tax rates. However, we do have very strong evidence that upper-income taxpayers actually paid more to the IRS because of the Reagan tax cuts.

This is presumably because wealthier taxpayers have much greater ability to control the timing, level, and composition of their income.

Lesson #3: Reagan Put the United States on a Path to Fiscal Balance

I already explained above why it is wrong to blame the Reagan tax cuts for the recession-driven deficits of the early 1980s. Indeed, I suspect most leftists privately agree with that assessment.

Source: CBO, Cato

But there’s still a widespread belief that Reagan’s tax policy put the United States on an unsustainable fiscal path.

Yet the Congressional Budget Office, as Reagan left office in early 1989, projected that budget deficits, which had been consistently shrinking as a share of GDP, would continue to shrink if Reagan’s policies were left in place.

Moreover, the deficit was falling because government spending was projected to grow slower than the private sector, which is the key to good fiscal policy.

The Border Tax

One of the ways the Trump administration intend to balance the books is through the imposition of border taxes. They may become embroiled in the quagmire of legal challenges, that they are in contravention of World Trade Organisation rules, but I shall leave that topic for another time.

This February 2017 article from the Peterson Institute – PIIE Debates Border Adjustment Tax is an excellent primer on the pros and cons of this controversial policy proposal. The Peterson conference delegates did manage to concur that the corporate tax rate should be lower – the Trump proposal would merely bring the rate in line with the current level of corporate tax in Germany. The delegates also agreed that some form of ad valorem tax should be introduced to make up the tax shortfall, although they accepted that this would directly encroach on individual State taxation systems. Peterson’s Adam Posen raised the valid concern that VAT tends to fall most heavily upon the poorest in society, thus increasing income inequality still further. Adjusting the tax system is always fraught with dangers.

At the heart of the Peterson debate was the impact a Border Adjustment Tax (BAT) would have on US businesses:-

Figure 1 below shows net exports to total trade in a sector, relative to how labor intensive the sector is. The size of the bubbles reflects the size of total trade in the sector. Two things are important: (1) Most industries are net importers, thus they believe they will be forced to raise prices under the proposal. (2) The industries that will gain the most—those with a relatively high labor cost share and positive net exports—are largely absent in the United States. The aerospace industry is the lone exception. This breakdown implies that many more big lobbies will be against the BAT than in favor.

Source: BLS, US Census Bureau

BAT revenues are estimated to be around $100bln per annum, about half the cost of the corporate tax cut, using the more conservative Tax Foundation estimate, however, this assumes that the trade deficit remains unchanged in response to the imposition of BAT. Whilst some countries will see their currencies decline versus the US$ the recent plight of the Mexican Peso begs caution. It depreciated from USDMXN 18.2 to 21 versus the US$ in the aftermath of the US election but has since recovered to around USDMXN 19.

Financial Market Response and Investment Opportunities

The table below shows the level of the US$ Index, S&P500 Stock Index and the US 10yr Government Bond Yield on elections week and yesterday:-

Source: Investing.com

It is worth noting that the US$ Index initially strengthened into the end of 2016, testing 104. It has subsequently moderated. 10yr bond yields also rose sharply, reaching 2.64%, but have since consolidated. It is the US stock market, which continues to achieve new all-time highs, which maintains faith in the pro-business credentials of the new administration.

The US bond market is dogged by the twin concerns of the fiscal profligacy of the government on the one hand and the hawkish intentions of the Federal Reserve, determined to normalise interest rates whilst they still can, on the other.

US GDP growth moderated in Q1. Commodity prices for staples, such as Iron Ore, Copper and Oil have diminished, as Chinese demand has waned of late. Meanwhile rising purchasing managers indices seem to be correlating with a rise in inventories. Personal income continues to growth slowly and personal savings has remains subdued, household debt to GDP is rising slightly but it remains well below the levels seen early in the decade. Consumers are unlikely to increase spending dramatically until they are more confident about long-term employment prospects. I wrote, last month about the impact of technology on jobs, in – Will technology change the prospects for emerging market growth? The impact on developed market employment will also be profound, but, I believe, it is also influencing the consumers’ response to higher prices. As prices rise, demand will fall. Central Banks should not target an inflation rate because it distorts the efficient working of the economy, but wage inflation, about which they are inclined to obsess, is likely to be subdued for a protracted period – years rather than months – by the effects of new technology.

Where does this leave stocks and bonds? Bond yields may rise if the US government deficit explodes: and a significant increase in bond yields will inevitably detract from the allure of the stock market. For the present, however, we continue to make new highs in stocks – the Nasdaq finally breached its, dot-com induced, 2000 highs at the end of April, after sixteen years – S&P500 valuations are high (a PE of 23 times and a CAPE of 27 times earnings) and yet “Buy American, Hire American” is a compelling slogan. As an international firm, hoping to continue selling your products to the United States, it makes sense to invest there. Pro-business US economic policy will continue to drive US stocks: the words of Pink Floyd spring to mind…we call it riding the gravy train.