- Rising commodity prices, including oil, are feeding through to PPI

- Unemployment data suggests wages may begin to rise faster

- Federal Reserve tightening will continue, other Central Banks may follow

- The bull market will be nine years old in March, the second longest in history

Since March 2009, the US stock market has been trending broadly higher. If we can continue to make new highs, or at least, not correct to the downside by more than 20%, until August of this year it will be the longest equity bull-market in US history.

The optimists continue to extrapolate from the unexpected strength of 2017 and predict another year of asset increases, but by many metrics the market is expensive and the risks of a significant correction are become more pronounced.

Equity volatility has been consistently low for the longest period in 60 years. Technical traders are, of course, long the market, but, due to the low level of the VIX, their stop-loss orders are unusually close the current market price. A small correction may trigger a violent flight to the safety of cash.

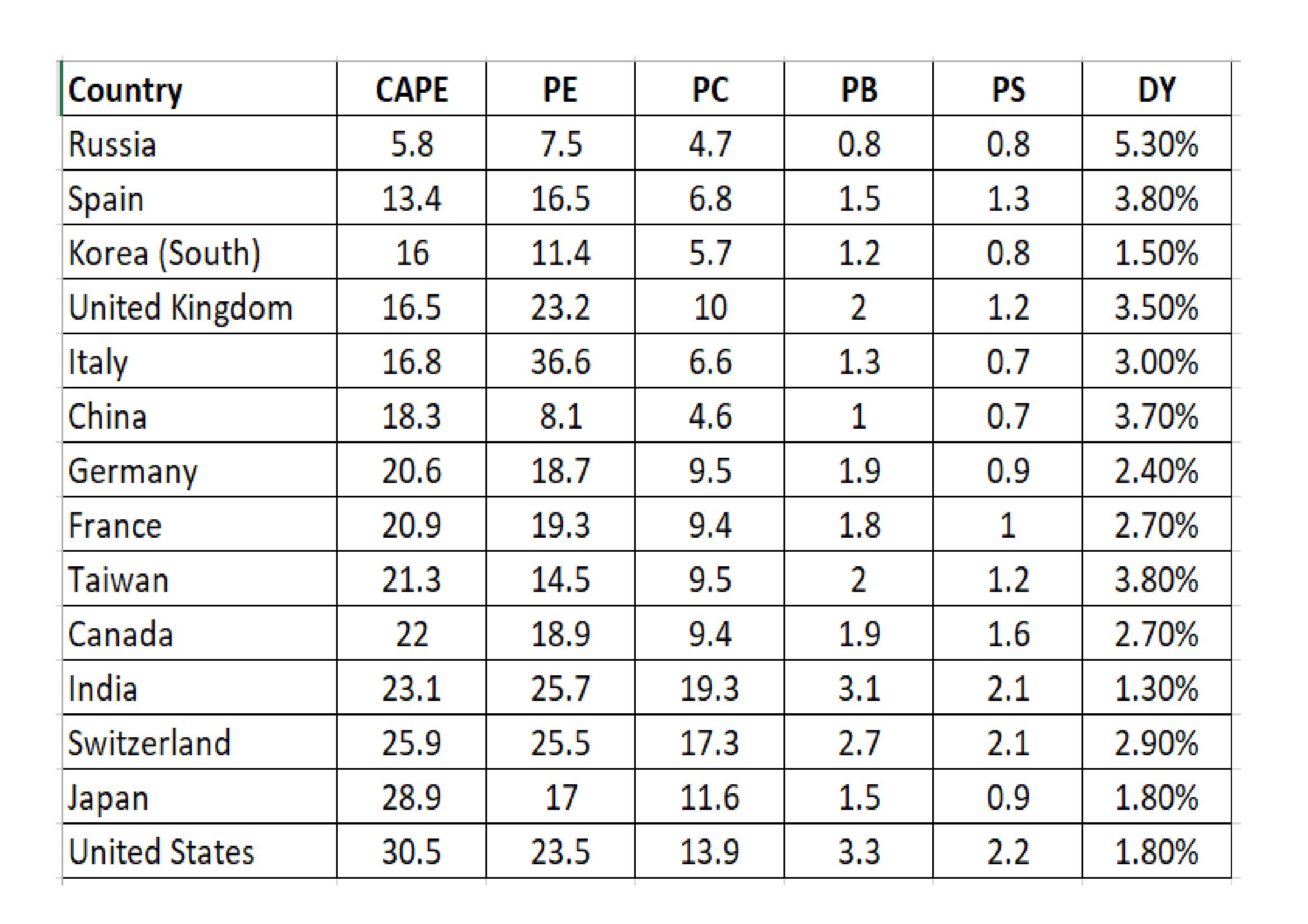

Meanwhile in Japan, after more than two decades of under-performance, the stock market has begun to play catch-up with its developed nation counterparts. Japanese stock valuation is not cheap, however, as the table below, which is sorted by the CAPE ratio, reveals:-

Source: Star Capital

Global economic growth surprised on the upside last year. For the first time since the great financial crisis, it appears that the Central Bankers experiment in balance sheet expansion has spilt over into the real-economy.

An alternative explanation is provided in this article – Is Stimulus Responsible for the Recent Improved Trends in the U.S. and Japan? – by Dent Research – here are some selected highlights:-

Since central banks began their B.S. back in 2001, when the Bank of Japan first began Quantitative Easing efforts, I’ve warned that it wouldn’t be enough… that none of them would be able to commit to the vast sums of money they’d ultimately need to prevent the Economic Winter Season – and its accompanying deflation – from rolling over us.

Demographics and numerous other cycles, in my studied opinion, would ultimately overwhelm central bank efforts…

Are such high levels of artificial stimulus more important than demographic trends in spending, workforce growth, and productivity, which clearly dominated in the real economy before QE? Is global stimulus finally taking hold and are we on the verge of 3% to 4% growth again?…Fundamentals should still mean something in our economy…

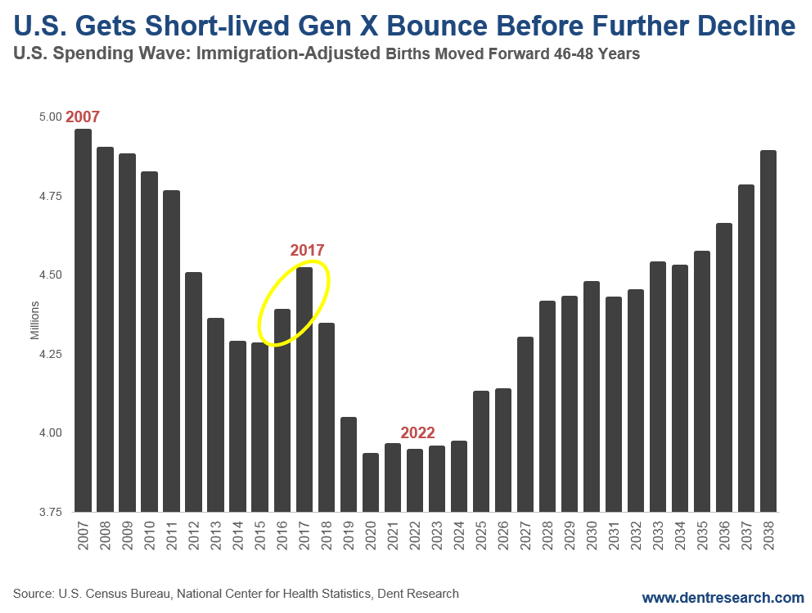

And my Generational Spending Wave (immigration-adjusted births on a 46-year lag), which predicted the unprecedented boom from 1983 to 2007, as well as Japan’s longer-term crash of the 1990s forward, does point to improving trends in 2016 and 2017 assuming the peak spending has edged to 47 up for the Gen-Xers.

The declining births of the Gen-X generation (1962 – 1975) caused the slowdown in growth from 2008 forward after the Baby Boom peaked in late 2007, right on cue. But there was a brief, sharp surge in Gen-X births in 1969 and 1970. Forty-seven years later, there was a bump… right in 2016/17…

Source: Dent Research

The next wave down bottoms between 2020 and 2022 and doesn’t turn up strongly until 2025. The worst year of demographic decline should be 2019.

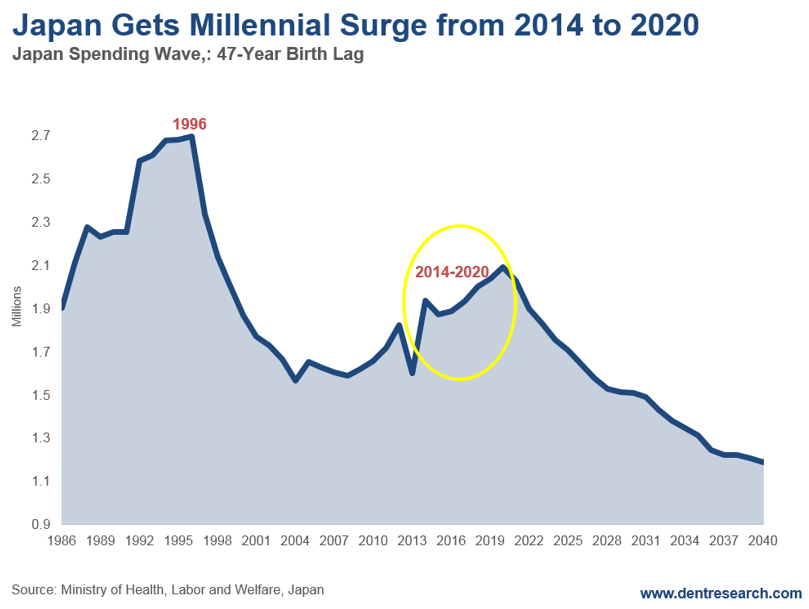

Japan has had a similar, albeit larger, surge in demographics against a longer-term downtrend.

Its Millennial generation brought an end to its demographic decline in spending in 2003. But the trends didn’t turn up more strongly until 2014, and now that they have, it’ll only last through 2020 before turning down dramatically again for decades…

Source: Dent Research

Prime Minister Abe is being credited with turning around Japan with his extreme acceleration in QE and his “three arrows” back in 2013. All that certainly would have an impact, but I don’t believe that’s what is most responsible for the improving trends. Rather, demographics is the key here as well, and this blip Japan is enjoying won’t last for more than three years!..

If demographics does still matter more, we should start to feel the power of demographics in the U.S. as we move into 2018.

If our economy starts to weaken for no obvious reason, and despite the new tax reform free lunch, then we will know that demographics still matter…

A different view of the risks facing equity investors in 2018 is provided by Louis-Vincent Gave of Gavekal, care of Mauldin Economics – Questions for the Coming Year – he begins with Bitcoin:–

…a recent Bloomberg article noted that 40% of bitcoins are owned by around 1,000 or so individuals who mostly reside in the greater San Francisco Bay area (the early adopters). Sitting in Asia, it feels as if at least another 40% must be Chinese investors (looking to skirt capital controls), and Korean and Japanese momentum traders. After all, the general rule of thumb in Asia is that when things go up, investors should buy more.

Asia’s fondness for chasing rising asset prices means that it tends to have the best bubbles. To this day, nothing has topped the late 1980s Taiwanese bubble, although perhaps, left to its own devices, the bitcoin bubble may take on a truly Asian flavor and outstrip them all? Already in Japan, some 1mn individuals are thought to day-trade bitcoins, while 300,000 shops reportedly have the capacity to accept them for payment. In South Korea, which accounts for about 20% of daily volume in bitcoin and has three of the largest exchanges, bitcoin futures have now been banned. For its part, Korea’s justice ministry is considering legislation that would ban payments in bitcoin all together.

At the very least, it sounds like the Bank of Korea’s recent 25bp interest rate hike was not enough to tame Korean animal spirits. So will the unfolding bitcoin bubble trigger a change of policy from the BoK and, much more importantly, from the Bank of Japan in 2018?

Mr Gave then goes on to highlight the risks he perceives as under-priced for 2018, starting with the Bank of Japan:-

In recent years, the BoJ has been the most aggressive central bank, causing government bond yields to stay anchored close to zero across the curve, while acting as a “buyer of last resort” for equities by scooping up roughly three quarters of Japanese ETF shares. Yet, while equities have loved this intervention, Japanese insurers and banks have had a tougher time. Indeed, a chorus of voices is now calling for the BoJ to let the long end of the yield curve rise, if only to stop regional banks hitting the wall.

Source: Gavekal/Macrobond

So could the BoJ tighten monetary policy in 2018? This may be more of an open question than the market assumes. Indeed, the “short yen” trade is popular on the premise that the BoJ will be the last central bank to stop quantitative easing. But what if this isn’t the case?

The author then switches to highlight the pros and cons. It’s the cons which interest me:-

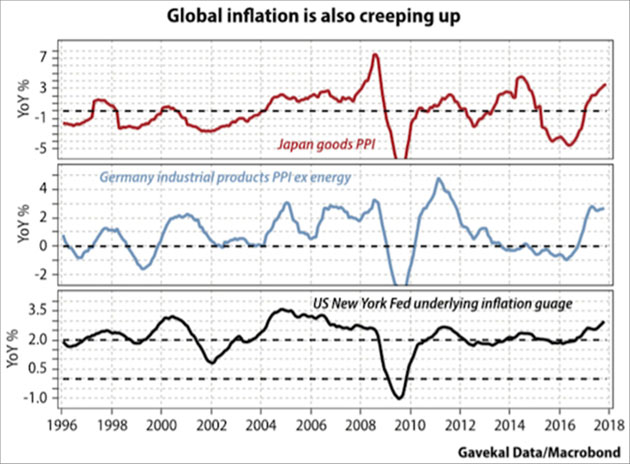

- PPI is around 3%

- The banks need a steeper yield curve to survive

- The trade surplus is positive once again

- The US administration has been pressuring Japan to encourage the Yen to rise

I doubt the risk of BoJ tightening is very great – they made the mistake of tightening too early on previous occasions to their cost. In any case, raising short-term rates will more likely lead to a yield curve inversion making the banks position even worse. The trade surplus remains small and the Yen remains remarkably strong by long-term comparisons.

This brings us to the author’s next key risk (which, given Gavekal’s deflationist credentials, is all the more remarkable) that inflation will surprise on the upside:-

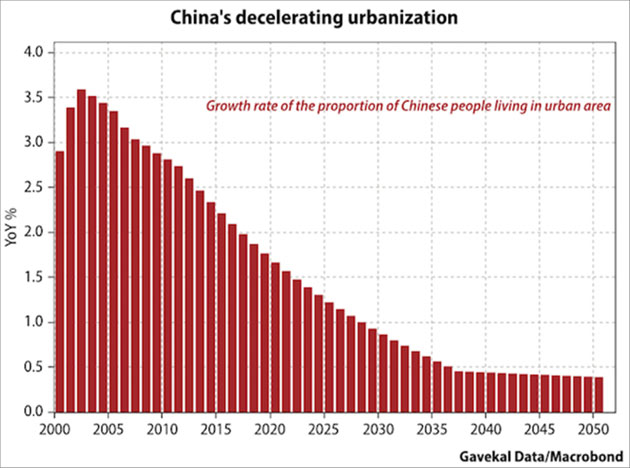

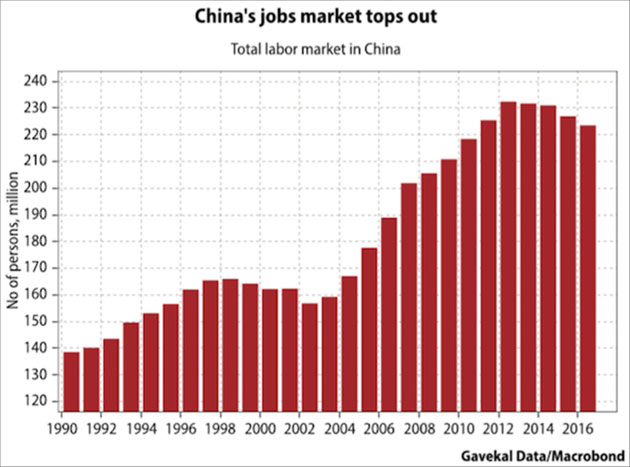

Migrant workers are no longer pouring into Chinese cities. With about 60% of China’s citizens now living in urban areas, urbanization growth was always bound to slow. Combine that with China’s aging population and the fact that a rising share of rural residents are over 40 (and so less likely to move), and it seems clear that the deflationary pressure arising from China’s urban migration is set to abate.

Reduced excess capacity in China is real: from restrictions on coal mines, to the shuttering of shipyards and steel mills, Xi Jinping’s supply-side reforms have bitten. At the very least, some 10mn industrial workers have lost their jobs since Xi’s took office (note: there are roughly 12.5m manufacturing workers in the US today!).

Source: Gavekal/Macrobond

Source: Gavekal/Macrobond

To say that most “excess investment” China unleashed with its 2015-16 monetary and regulatory policy stimulus went into domestic real estate is only a mild exaggeration. Very little went into manufacturing capacity, which may explain why the price of goods exports from China has, after a five-year period, shown signs of breaking out on the upside. Another part of the puzzle is that Chinese producer prices are also rising, so it is perhaps not surprising that export prices have followed suit. The point is, if China’s export prices do rise in a concerted manner, it will happen when inflation data in the likes of Japan, the US and Germany are moving northward…

Source: Gavekal/Macrobond

Source: Gavekal/Macrobond

…The real reason I worry about inflation today is that inflation has the potential to seriously disrupt the happy policy status quo that has underpinned markets since the February 2016 Shanghai G20 meeting.

Mr Gave recalls the Plaza and Louvre accords of 1985 and ‘87, reminding us that the subsequent rise in bond yields in the summer of 1987 brought the 1980’s stock market bubble to an abrupt halt.

…for the past 18 months, I have espoused the idea that, after a big rise in foreign exchange uncertainty – triggered mostly by China with its summer 2015 devaluation, but also by Japan and its talk of helicopter money, and by the violent devaluation of the euro that followed the eurozone crisis – the big financial powers acted to calm foreign exchange markets after the February 2016 meeting of the G20 in Shanghai.

…as in the post-Louvre accord quarters, risk assets have broadly rallied hard. It’s all felt wonderful, if not quite as care-free as the mid-1980s. And as long as we live under this Shanghai accord, perhaps we should not look a gift horse in the mouth and continue to pile on risk?

This brings me to the nagging worry of “what if the Shanghai agreement comes to a brutal end as in 1987?”

Again the author is at pains to point out that, for the bubble to burst an inflation hawk is required. A Central Bank needs to assume the mantle of the Bundesbank of yesteryear. He anticipates it will be the PBoC:-

…(let’s face it: the last two upswings in global growth, namely 2009 and 2016, were triggered by China more than the US). Indeed, the People’s Bank of China may well be the new Bundesbank for the simple reason that most technocrats roaming the halls of power in Beijing were brought up in the Marxist church. And the first tenet of the Marxist faith is that historical events are shaped by economic forces, with inflation being the most powerful of these. From Marx’s perspective, Louis XVI would have kept his head, and his throne, had it not been for rapid food price inflation the years that preceded the French Revolution. And for a Chinese technocrat, the Tiananmen uprising of 1989 only happened because food price inflation was running at above 20%. For this reason, the one central bank that can be counted on to be decently hawkish against rising inflation, or at least more hawkish then others, is the PBoC.

Mr Gave foresees inflation delivering a potential a triple punch; lower valuations for asset markets, followed by tighter monetary and fiscal policy in China, which will then trigger an incendiary end to the unofficial ‘Shanghai Agreement’. In 1987 it was German Bunds which offered the safe haven, short-dated RMB bonds may be their counterpart in the ensuing crisis.

This brings our author to the vexed question of the way in which the Federal Reserve will respond. The consensus view is that it will be business as usual after the handover from Yellen to Powell, but what if it’s not?

…imagine a parallel universe, such that within a few months of being sworn in, Powell faces a US economy where:-

Unemployment is close to record lows and government debt stands at record highs, yet the federal government embarks on an oddly timed fiscal stimulus through across-the-board tax cuts.

Shortly afterwards, the government further compounds this stimulus with a large infrastructure spending bill.

As inflationary pressures intensify around the world (partly due to this US stimulus), the PBoC, BoJ and ECB adopt more hawkish positions than have been discounted by the market.

The unexpected tightening by non-US central banks leads other currencies higher, and the US dollar lower.

The combination of low interest rates, expansionary fiscal policy and a weaker dollar causes the US economy to properly overheat, forcing the Fed to tighten more aggressively than expected.

Gave proposes four scenarios:-

- More of the same – along the lines of the current forecasts and ‘dot-plot’

- A huge US fiscal stimulus forcing more aggressive tightening

- An unexpected ‘shock’ either economic or geopolitical, leading to renewed QE

- The Fed tightens but inflation accelerates and the rest of the world’s Central Banks tighten more than expected

…In the first two scenarios, the US dollar will likely rise, either a little, or a lot. In the latter two scenarios, the dollar would likely be very weak. So if this analysis is broadly correct, shorting the dollar should be a good “tail risk” policy. If the global economy rolls over and/or a shock appears, the dollar will weaken. And if global nominal GDP growth accelerates further from here, the dollar will also likely weaken. Being long the dollar is a bet that the current investment environment is sustained.

The final risk which the author assesses is the impact of rising oil prices. It has often been said that a rise in the price of oil is a tax on consumption. Louis-Vincent Gave gives us an excellent worked example:-

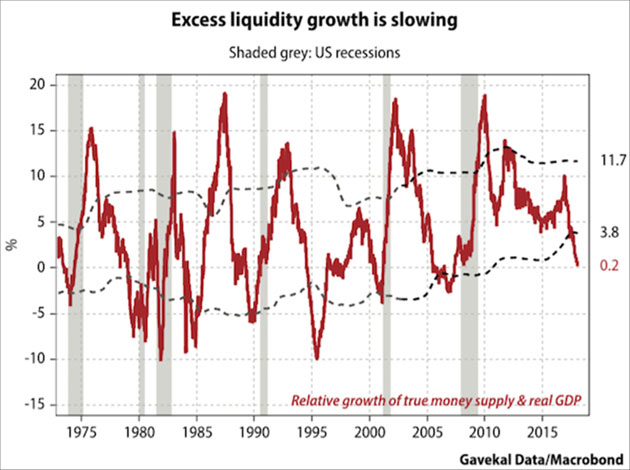

…assume that the world consumes 100mn barrels of oil a day…Then further assume that about 100 days of inventory is kept “in the system”… if the price of oil is US$60/bbl, then oil inventories will immobilize around US$600bn in working capital. But if the price drops to US$40/bbl, then the working capital needs of the broader energy industry drops by US$200bn.

The chart below shows the decline in true money supply:-

Source: Gavekal/Macrobond

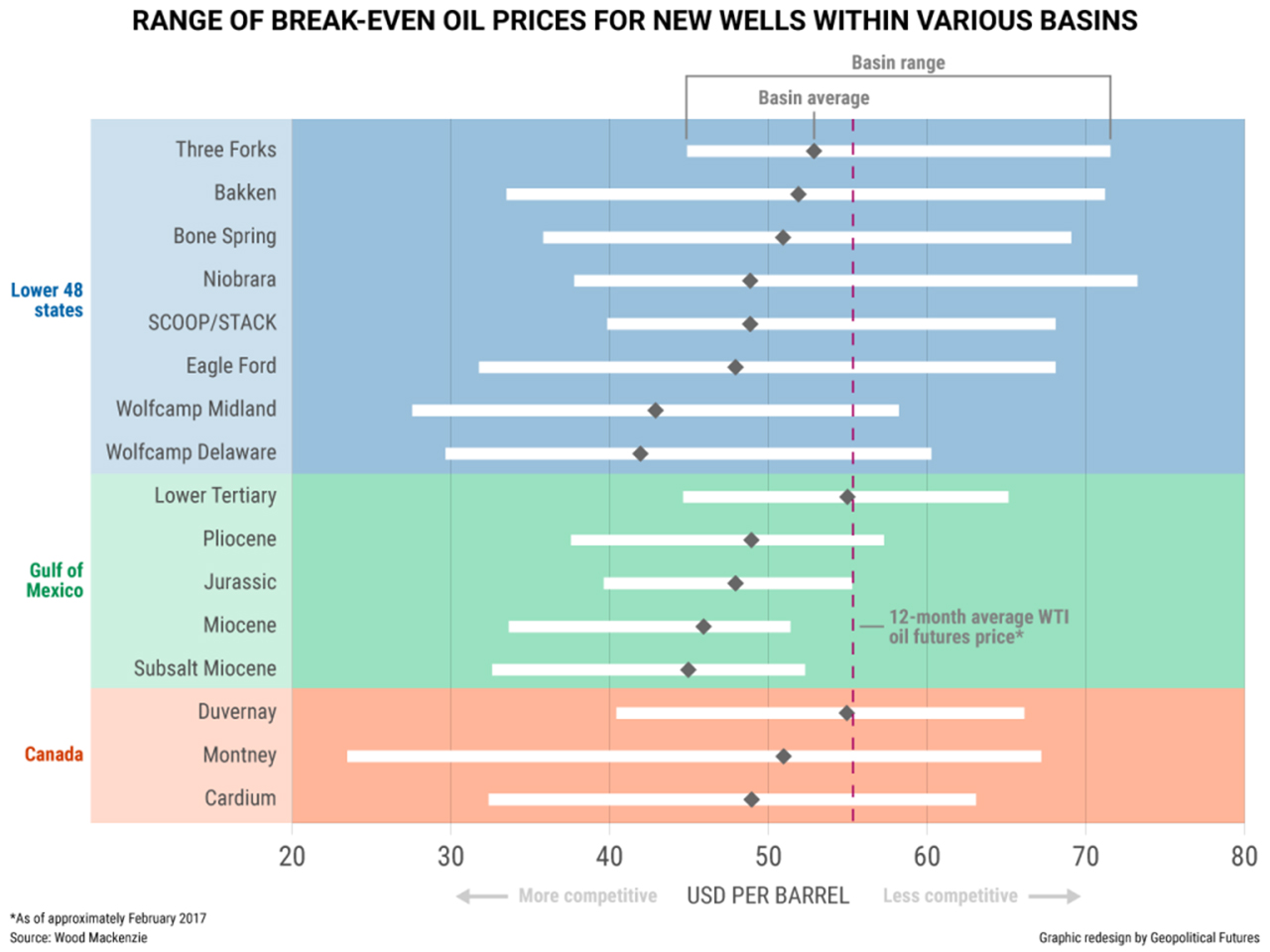

The Baker Hughes US oil rig count jumped last week from 742 to 752 but it is still below the highs of last August and far below the 1609 count of October 2014. The break-even oil price for US producers is shown in the chart below:-

Source: Geopolitical Futures

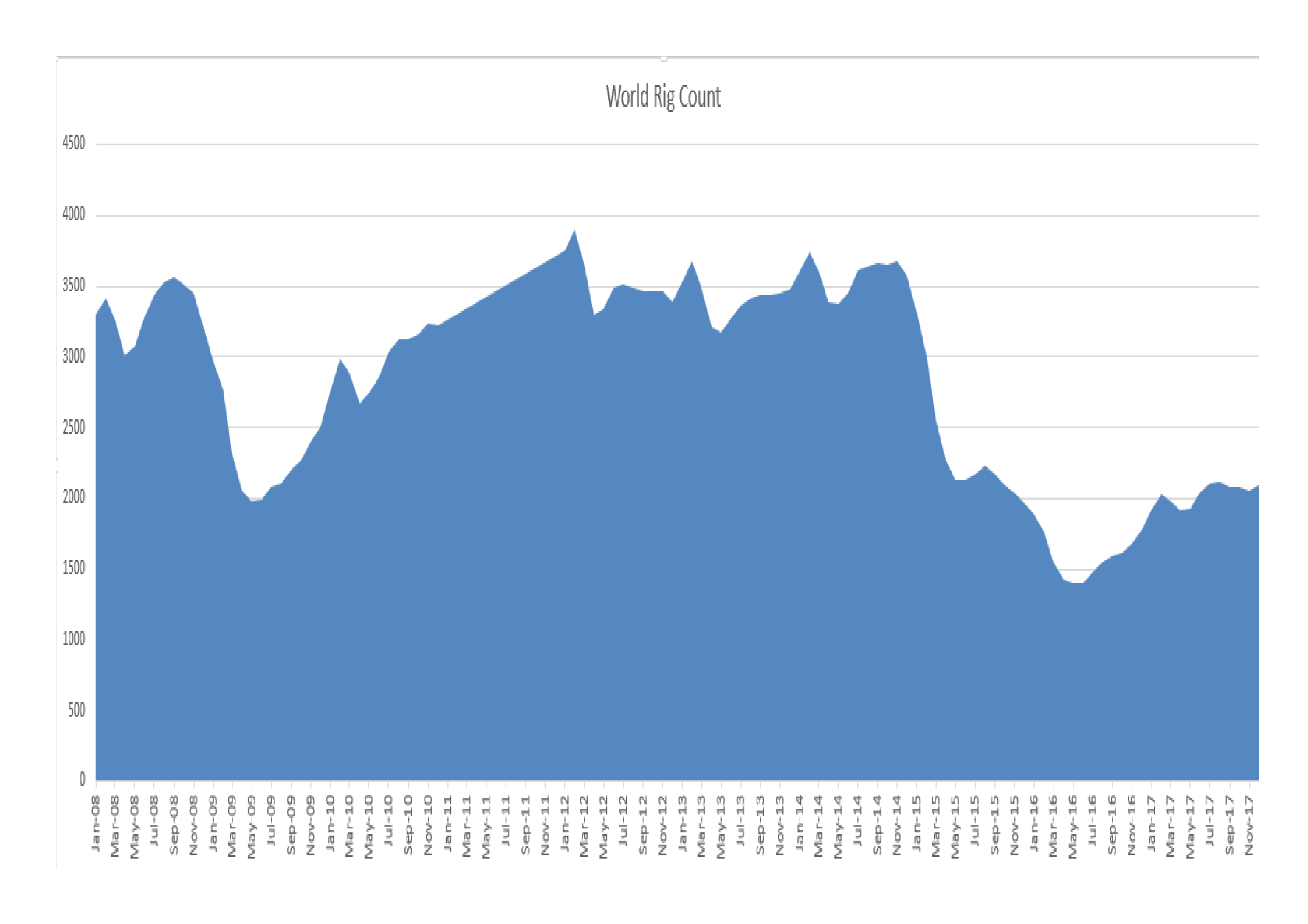

If the global price of oil were entirely dependent on the marginal US producer, there would be little need to worry but the World Rig Count has also been slow to respond and Non-US producers are unable to bring additional rigs on-line as quickly, in response to price rises, as their US counterparts:-

Source: Baker Hughes

An additional concern for the oil price is the lack of capital investment over recent years. Many of the recent fracking wells in the US are depleting more rapidly. This once dynamic sector may have become less capable of reacting to the recent price increase. I’m not convinced, but a structurally higher oil price is a risk to consider.

Conclusion and investment opportunities

As Keynes famously said, ‘The markets can remain irrational longer than I can remain solvent.’ Global equity markets have commenced the year with gusto, but, after the second longest bull-market in history, it makes sense to be cautious. Growth stocks and Index tracking funds were the poster children of 2017. This year a more defensive approach is warranted, if only on the basis that lightening seldom strikes twice in the same place. Inflation may not become broad-based but industrial metals prices and freight rates have been rising since 2016. Oil has now broken out on the upside, monetary tightening and balance sheet reduction as the watch words of the leading Central Banks – even if most have failed to act thus far – these actions compel one to tread carefully.

A traditional value-based approach to stocks should be adopted. Japan may continue to play catch up with its developed nation peers – the demographic up-tick, mentioned by Dent research, suggests that the recent breakout may be sustained. The Federal Reserve is leading the reversal of the QE experiment, so the US stock market is probably most vulnerable, but the high correlations between global stock markets means that, if the US stock market catches a cold, the rest of the world is unlikely to avoid infection.

High-yield bonds have been the alternative to stocks for investors seeking income for several years. Direct lending and Private Debt funds have raised a record amount of assets in the past couple of years. If the stock market declines, credit spreads will widen and liquidity will diminish. In the US, short dated government bond yields have been rising steadily and yield curves have been flattening, nonetheless, high grade floating rate notes and T-Bills may be the only place to hide, especially if inflation should rise even as stocks collapse.

There will be a major stock market correction at some point, there always is. When, is still in doubt, but we are nearer the end of the bull-market than the beginning. Technical analysis suggests that one must remain long, but in the current low volatility environment it makes sense to use a trailing stop-loss to manage the potential downside risk. Many traders are adopting a similar strategy and the exit will be crowded when you reach the door. Expect slippage on your stop-loss, it’s a price worth paying to capture the second longest bull-market in history.