|

| 50 SEK banknote issued by the Riksbank in 1960 |

“Do we need an eKrona?” asks Stefan Ingves, the Governor of the Riksbank, Sweden’s central bank. The Riksbank is probably the central bank that has advanced the furthest in discussions surrounding the introduction of a central bank-issued digital currency (CBDC)—a new form of risk-free digital money for use by the public. Canada, New Zealand, Australia, the ECB, and China are also dissecting the idea, with more central banks to come in 2018.

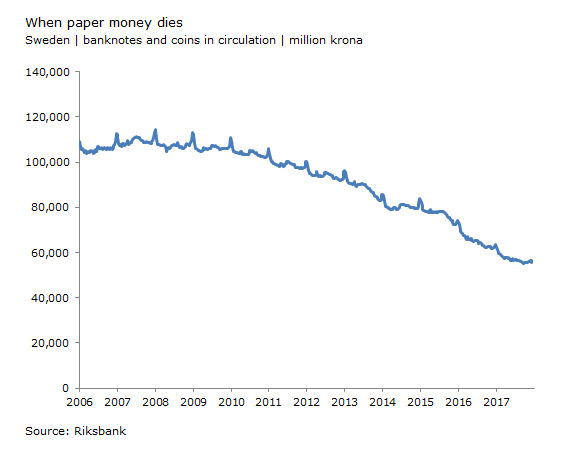

Sweden is approaching the issue from a unique angle, says Ingves. It is the only country in the world showing a consistent decline in cash and coin usage. I’ve written about this interesting pattern here, here, and here. Below is a chart:

Ingves floats two theories. Either the Swedish public no longer wants central bank money, or alternatively they do want central bank money but not the type that is “made of pieces of paper,” preferring instead an as-yet non-existent digital alternative. If so, then it may be the Riksbank’s duty to provide that alternative, says Ingves.

Duty is an admirable motivation, but let me propose another reason for why the Riksbank is exploring the idea of an eKrona—self preservation. I think Sweden’s central bank is terrified that it will become powerless in the future. It is desperately casting around for solutions to resuscitate itself, one of these being an eKrona. This fear is rooted in the fact that declining cash usage has led to a collapse in the resources that the Riksbank believes that it needs to function.

These worries about powerlessness are shared by central bankers around the world, many of whom expect advances in private payments technology to lead them to the same cash-light world that Sweden is currently entering. Their respective degrees of discomfort probably depend on how advanced their citizens are in the process of shifting away from cash. The Federal Reserve, which issues the world-renown $100 bill, is perhaps the farthest from having to worry, whereas central banks like the Norges Bank and Central Bank of Iceland are much closer to approaching peak cash.

What do I mean by a collapse in resources? Central banks have always been unique among government agencies for their self-sufficiency. Rather than depending on tax revenues to pay for their operations, they are capable of funding themselves internally. Central bankers like Ingves have even made a habit of providing their masters in government with a juicy dividend each year.

The magic behind this ability to self-fund is due to the central bank’s monopoly on banknotes. Banknotes get into circulation when a central banker buys an asset, usually a government bond. Because the central bank doesn’t have to pay any interest on the banknotes whereas the bonds it holds yield 4% or so, it gets to collects the entire 4% margin for itself as revenue. Out of those revenues it pays its expenses, the remaining profit flowing back to the government as a dividend.

These dependable and juicy margins, otherwise known as seigniorage, have afforded central bankers a number of luxuries. First, consider the creature comforts. These include large research departments, well-paid staff, good benefits, high status, nice new office buildings, museums with free admission, and plenty of international travel and conferences.

But seigniorage also serves a more important function; as fuck you money. Fuck you money (pardon the expletive, but its such a great phrase) can be thought of as any resource base that is large enough to allow an individual or institution to reject traditional hierarchies (i.e. one’s boss) without fearing the consequences. The central bank’s seigniorage—its fuck you money—finances a dividend that flows to the government, effectively buying central bankers a uniquely-large degree of autonomy from the vagaries of their political masters. This safe space allows folks like Ingves to pursue their most important task in peace, namely jigging the interest rate up and down in order to set the price level. A government department that must pass around the hat each year in order to get funding would never be able to attain the same degree of independence.

At this point you may be able to see the Riksbank’s problem. As the supply of krona banknotes in circulation withers, the Riksbank’s seigniorage is getting smaller and smaller. This threatens not only the creature comforts that Swedish central bankers have gotten used to, but also the flows of fuck you money necessary to secure their sacred independence. If the popularity of kronor banknotes continues to drop, the perceived risks of political subjugation of the central banking machine will only grow.

Let’s take a look at some numbers. Below is a chart of Riksbank seigniorage going back to 2008.

The Riksbank calculates this number by taking the total earnings from its assets (both income and capital gains) and allocating an appropriate portion of this to the banknote component of its liabilities. The total costs of managing the bank note and coin system (printing, handling, salaries, designing etc) are deducted from this amount, leaving banknote seigniorage as the remainder.

Whereas Riksbank seigniorage clocked in at around SEK 5 billion in the late 2000s, it has plunged to SEK 560 million in 2016. If the rate of decline in banknote usage continues, my calculations show that seigniorage could fall to half that amount by 2018 and go into negative territory at some point in the early 2020s.

Falling global nominal interest rates are one important explanation for the decline in Riksbank seigniorage. As I said earlier, central bankers garner the margin between the supply of 0%-yielding banknotes in circulation and the interest payments they earn on bonds. If bond rates are declining, the margin shrinks and seigniorage suffers. But even if Swedish interest rates were to slowly recover over the next few years, this wouldn’t halt the deterioration in Riksbank seigniorage. The constantly eroding base of banknotes on which the Riksbank relies for its profits would more-than-cancel out the effects of higher rates.

To shore up its flow of fuck you money, the Riksbank needs to find other sources of income. Which may be the true reason for Ingves’s recent broaching of the idea of an eKrona. Given that a decline in banknotes in circulation is at the heart of the Riksbank’s flagging seigniorage, then perhaps the development of a new 0%-yielding product will allow the Riksbank to rebuild its once plentiful resources.

In terms of design, one option the Riksbank is putting forward is to allow Swedes to keep accounts directly at the central bank. It refers to this option as register-based eKrona. I’m afraid that register-based eKrona is destined to be a dud. Private banks have decades worth of experience in providing accounts to the public. A central bank account will always be a poor competitor. Former New Zealand central banker Michael Reddell recently blogged on the topic of an eNZD, recalling the days when his employer offered accounts to employees:

Central banks almost inevitably would lag behind commercial banks in their technology anyway, which wouldn’t make a central bank transactions account product particularly attractive… Frankly, I’d be a bit surprised if there was much (normal times) demand at all (and I think back to the days – decades ago – when the Reserve Bank offered – in direct competition with the private banks – cheque accounts to its own staff; perhaps some people used theirs extensively, but I used it hardly at all).

As for the supposed superior credit risk of a central bank account, I just don’t see it. Sweden already insures private bank accounts for up to 950,000 kronor ($112,500) and even up to 5 million kronor in special circumstances. A central bank account could only be the superior alternative for amounts north of $112,500, but how many members of the public really keep that much in deposits?

|

| Types of eKrona compared to cash and bank account money (source) |

Given that register-based eKrona would fail miserably in securing the Riksbank a new stream of fuck-you money, Ingves and his research staff should probably be focusing entirely on the alternative form for eKrona: electronic banknotes. The Riksbank refers to this option as value-based eKrona. Unlike register-based eKrona, a value-based eKrona would possess a very special feature; anonymity. Like physical banknotes, they would be untraceable, only they would be superior to their physical forbears since they would be transferable not only face-to-face but also over the internet. The Swedish public’s desire for online economic privacy would be sufficient to generate a positive demand for eKrona—after all, it is the lone product providing said services—thus restoring at least some part of the Riksbank’s lost seigniorage.

In his recent speech, Ingves seems tepid on the idea of privacy for the eKrona, blithely writing that “perhaps it could contain some element of anonymity.” Here’s a message for him (and all those other central bankers who will eventually be in Ingves’s position). “Perhaps” isn’t good enough. Without a differentiating feature like anonymity, eKrona will never gain any acceptance among a public that already has decent private bank digital money. And so the Riksbank will only continue on its path to losing its wellspring of fuck you money and the independence it buys. Anonymous digital money or bust.

Source: http://jpkoning.blogspot.co.uk/