(This paper is an expanded version of the first Adam Smith Lecture presented on September 24, 2018, at the Panmure House, Edinburgh, Scotland, sponsored by the Edinburgh School of Business.)

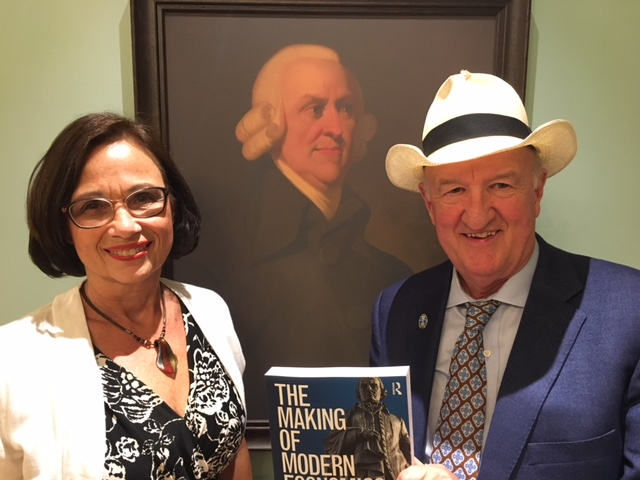

It is a supreme pleasure to give the first Adam Smith Lecture in this newly refurbished Panmure House here in Edinburgh, Scotland, the home where Adam Smith lived for the final dozen years of his life as he served as the Commissioner of Customs. It was here that Smith produced four editions of his famous work, The Wealth of Nations. I wish to thank Professor Keith Lumsden and everyone at the Edinburgh School of Business involved in this important project for inviting me to speak on this special occasion.

I wish to take this opportunity to talk about my own sojourn in which I made Adam Smith and his system of natural liberty the heroic figure in my book, The Making of Modern Economics, and the contributions I have made in the history of economic thought.

My contributions consist of the following:

First, The Making of Modern Economics: Lives and Ideas of the Great Economic Thinkers is the first one-volume history of economics written from a market-friendly perspective.[1] Until its publication, almost all other histories of thought were written by socialists, Keynesians and Marxists.

Second, my book applies an alternative to the traditional pendulum “left-right” approach to the political spectrum — a totem pole of economics, where economic thinkers are ranked from top to bottom.

Third, my work creates for the first time a real story line in the history of economics, with a primary protagonist; a cunning plot where the hero faces his enemies and is sometimes left for dead, only to be rescued by his friends; and a happy ending. The running storyline is Adam Smith’s “system of natural liberty,” where every economist is measured to the extend they support or add to the house that Adam Smith built, or are critics who want to tear down and replace Smith’s model with their own.

To explain how this new pedagogy came about, let me tell my own story about how The Making of Modern Economics came into being.

The Origin: Commissioning Murray Rothbard

The genesis of my work goes back to 1980, when I commissioned the libertarian economist Murray Rothbard to write a free-market alternative to the bestselling book, The Worldly Philosophers, by the late Robert Heilbroner. No better title has been found for the “lives and ideas of the great economic thinkers” from Adam Smith on. Heilbroner’s little book has been immensely popular, for both students and laymen, having sold over four million copies. Unfortunately, Heilbroner was a socialist whose favorite economists were Karl Marx, Thorstein Veblen, and John Maynard Keynes. He ignored the ideas of the French laissez faire school of J. B. Say and Frederic Bastiat; the Austrian school of Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek; and the monetarist school of Irving Fisher and Milton Friedman. In fact, he didn’t even mention Milton Friedman’s name in the latest edition. The reader deserved a more balanced approach.

I also found the way the history of economics was taught in college to be frustrating. One of the most disappointing classes I took as an undergraduate was in the history of economic ideas. The course was convoluted, the text was dry (with few anecdotes and no pictures), the lives of economists seemed uninteresting, and even the A students came away from the class wondering whether economists made any sense at all. Typically students in economics were exposed to a wide range of schools of thought — neoclassical, Keynesian, monetarist, Austrian, supply side, institutionalist, and Marxist — without any effort to determine the veracity of their theories.

In sum, the story of economics was told in a haphazard and disjointed way. In a sense, there was no story at all. There was no running plot, no engaging drama, and no single heroic figure. Economists came and went on the pages of history, with no sense that the science was advancing or regressing. In my readings of the histories of economic philosophy, they all lacked a running storyline, and a consistent point of view that allows the student to realize when an academic scribbler was heading down the wrong road, or off a cliff.

For years, I searched for a new approach. I asked some of my friends who I should approach to write a contra-Heilbroner history. Larry Wimmer, my mentor at BYU, suggested George Stigler, the Chicago economist, but I worried about his biting sarcasm and his criticism of the Austrian school.

I considered Murray Rothbard, the iconoclastic Austrian economist, to be a better choice. One day in 1980 I called him on the telephone and asked him what he thought about the idea of writing a contra-Heilbroner history of thought. He was enthusiastic and loved the idea, saying that he always wanted to write a libertarian version. So we readily agreed, and I paid him a handsome advance of $20,000, so that he would concentrate of this work among his many other projects. He promised that he would deliver a 12-chapter history in 12 months, and the book would not go beyond 300 pages, the same length as Heilbroner’s.

Then the waiting game began…

One year passed. Two years. Three years. No completed manuscript. No 300 pages. No layman’s discourse. No Adam Smith. Murray was writing all right, but he was not writing a Heilbroner bestseller for the general public. He was writing and researching what we call a Schumpeterian tome for graduate students: a multi-volume, dense history of economic thought for professionals and advanced students.

In the 1940s, Joseph Schumpeter, the Austrian economist and iconoclastic Harvard professor, wrote his voluminous History of Economic Analysis, which reached 1,260 pages by the time it was published. Rothbard’s laborious work began with Aristotle and the Greeks, moving slowly along to the Catholic Fathers and the Enlightenment, and finally, by chapter 16, reaching the celebrated Adam Smith.

I was an admirer of Murray Rothbard as a libertarian economist and radical historian, but I could see that this was not what I had bargained for. Years later, after tiring of asking the question, “Have you reached Marx yet?” I sent Murray a copy of a Harvard Crimson interview with Joseph Schumpeter, who said in 1944, “My research program grows longer and my life shorter. My History of Economic Analysis drags, and I am always hunting other hares.” Rothbard was apparently following the same path.

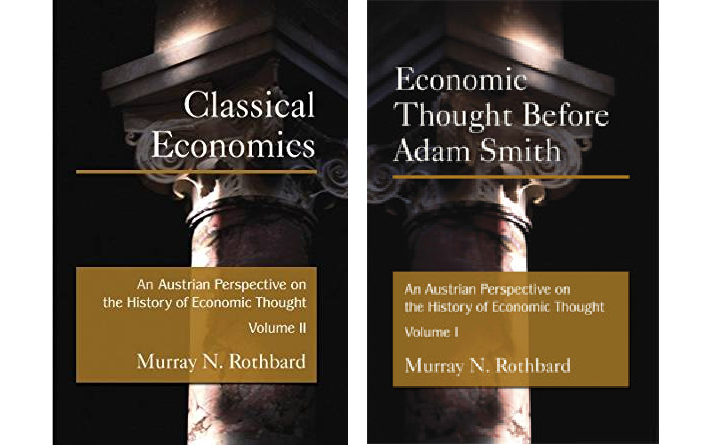

Fifteen years later — 1995 — Edward Elgar (the publisher, not the composer) published the first two volumes of Rothbard’s history, “Economic Thought Before Adam Smith” (556 pages) and “Classical Economics” (528 pages). Rothbard’s first volume ends with his famous (and critical) chapter on Adam Smith; and his second volume ends with his chapter on Karl Marx. I have enjoyed reading Rothbard’s stimulating and often cutting remarks, and agree with much of what he wrote (with the strong exception of his attack on Adam Smith). But he never finished the job.

I frequently commented to friends that Murray was writing a Schumpeterian tome, which also meant that he would probably die before completing the book. After Schumpeter’s death in 1950, his devoted wife, Elizabeth, tried to get the almost finished manuscript ready for publication. She also passed away before completing the task, and the manuscript was prepared for publication by Harvard colleagues, and published by Oxford University Press in 1954.

Sadly, my concern became prophetic. Murray Rothbard died of a heart attack in New York City in January 1995, at the age of 69, only a few weeks before the first copies of his two-volume work appeared (I believe I was the first person to be receive the two volumes in the mail). He never got to the next two planned volumes.

My Turn to Write a One-Volume History

After Murray’s unexpected passing, I realized that the contra-Heilbroner work had yet to be written. Like other libertarians, I admired most of Murray Rothbard’s contribution, but it wasn’t a Heilbroner alternative. It was a Schumpeter alternative.

I finally came to the conclusion that perhaps I myself had prepared sufficiently to write the first one-volume history of economics from a free-market perspective. In the 1980s I had written my work The Structure of Production, a treatise on Austrian macroeconomics, that was both historical and theoretical. It was published in 1990 by New York University Press. Then in 1991, I came out with Economics on Trial, a review of the top-ten textbooks in economics, which included studies of all the major schools of thought, and a year later an edited volume, Dissent on Keynes.

So I began writing my first chapter entitled “It All Started with Adam” (Adam Smith, that is). At the time, I was still heavily under the influence of Rothbard, so my first chapter was largely a negative assessment of Adam Smith. Rothbard held the unconventional view that Smith apostatized from the sound doctrines and theories previously developed by pre-Adamites such as Richard Cantillon, Anne Robert Turgot, and the Spanish scholastics. He asserted that Adam Smith’s contributions were “dubious” at best, that “he originated nothing that was true, and that whatever he originated was wrong,” and that The Wealth of Nations was “rife with vagueness, ambiguity and deep inner contradictions.” Specifically, his doctrine of value was an “unmitigated disaster”; his theory of distribution was “disastrous”; his emphasis on the long run was a “tragic detour”; and Smith’s putative “sins” include support for progressive taxation, fractional reserve banking, usury laws, and a crude labor theory of value that Marxists later borrowed from Adam Smith and David Ricardo.[2]

At the time my assessment of Adam Smith followed similar lines. I didn’t feel completely comfortable with this first chapter, but I was on my way.

The Adam Smith Debate

After writing the first chapter, I took it with me on a trip to Utah, and showed it to my uncle Cleon. Uncle Cleon was a wise old man I respected as a towering figure in law, politics and religion. I asked him to read the chapter. When I handed him the first chapter, he turned to me and said with considerable feeling, “You know, Mark, the Adam Smith doctrine of the invisible hand is inspired of God.”

His statement shocked me. I thought to myself, “If my uncle is right, I need to rewrite this chapter and start over.”

Later I read Ludwig von Mises’s introduction to Regnery’s edition of The Wealth of Nations, which Mises called a “great book.” According to Mises, Smith’s works are “the consummation, summarization, and perfection…of a marvelous system of ideas…presented with admirable logical clarity and an impeccable literary form…. [representing] the essence of the ideology of freedom, individualism, and prosperity.” Furthermore, “Its publication date — 1776 — marks the dawn of freedom both political and economic….It paved the way for the unprecedented achievements of laissez-faire capitalism.” He concluded, “There can hardly be found another book that could initiate a man better into the study of the history of modern ideas and the prosperity crated by industrialization.”[3]

So I struggled with the question, “Who’s right? Murray Rothbard, the professional economist and my mentor, or my wise old Uncle Cleon, who is not an economist by training but somebody I admire, or even better Ludwig von Mises, Rothbard’s mentor?”

There was only one way to find out. I decided to read Adam Smith’s magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations, cover to cover, and decide for myself.

So for the next two months I read day after day all 975 pages of The Wealth of Nations. (I still have that well-marked Modern Library edition on my bookshelf.) Two months later, I put the book down, and concluded without any doubt: Murray Rothbard is wrong and my Uncle Cleon, and Ludwig von Mises, are right. Adam Smith’s “system of natural liberty” and The Wealth of Nations, despite its sometime significant errors, are an inspiring and profound work that deserves to be the central message of the book.

I immediately tore up the first chapter and started rewriting it, and suddenly the whole theme of the book became clear. I now had a powerful running plot, the development of an economic science based on Adam Smith’s “system of natural liberty” (freedom, competition, and justice). The first chapter was built around the “invisible hand” doctrine or what was later described as “the first fundamental theorem of welfare economics.” The book had a singular hero (Adam Smith, the father of modern economics), and a series of characters and events that either advanced or impeded the house that Adam Smith built. In the words of George Stigler, the competitive model of Adam Smith became the “crown jewel” of economics, “the most important substantive proposition in all of economics. Smith had one overwhelmingly important triumph: he put into the center of economics the systematic analysis of the behavior of individuals pursuing their self-interest under conditions of competition.”

By establishing an heroic figure in the development of economics, I found that it was possible to judge all economic characters on the stage of ideas. The first chapter begins with Adam Smith, the heroic figure, and thereafter economists are ranked to the extent that they promoted or detracted from Smith’s “system of natural liberty.” Thus, Karl Marx, Thorstein Veblen, John Maynard Keynes, Joseph Stiglitz, and even some Smith’s disciples such as Robert Malthus and David Ricardo undermined the Smithian model of democratic capitalism during periods of economic failure and upheaval, while J. B. Say, Carl Menger, Alfred Marshall, Irving Fisher, Ludwig von Mises, and Milton Friedman, among others, remodeled and improved upon Smithian economics as the world economy recovered and prospered. My history unfolded as Smith and his system of natural liberty came under frequent attack, such as during the Industrial Revolution, and were sometimes left for dead, such as in the Great Depression, but were always resuscitated and reinvigorated by supporters. The collapse of the Soviet socialist central planning model in 1989-92 represented a triumph of the Adam Smith model. Thus, the story of economics had a good ending (albeit muddied by the financial crisis of 2008).

In short, I made a discovery. For the first time, economics could be told as a story, with a plot, a hero and a good ending. Hence, the title: The Making of Modern Economics. (I originally suggested to the publisher that we call it “The Story of Economics,” but he rejected it on the grounds that it was not an academic title.) Milton Friedman caught the vision of my book when he said, after reading it, “All histories of thought are BS–Before Skousen.”

To summarize, all previous histories of economic ideas tended to give a dry, disjointed, and helter-skelter account of economists and their contradictory theories. But The Making of Modern Economics unifies the story of economics for the first time by ranking all major economic thinkers either for or against the invisible hand doctrine of Adam Smith. Thus, Marx, Veblen and Keynes are viewed as critics of Smith’s doctrine, while Marshall, Hayek and Friedman are seen as defenders.

Using this ranking system, Making offers a full-scale review and critique of every major school and their theories, including classical, Keynesian, monetary, Austrian, institutionalist, and Marxist.

The Pendulum vs. Totem Pole Approach

There are some other contributions I made in writing The Making of Modern Economics.

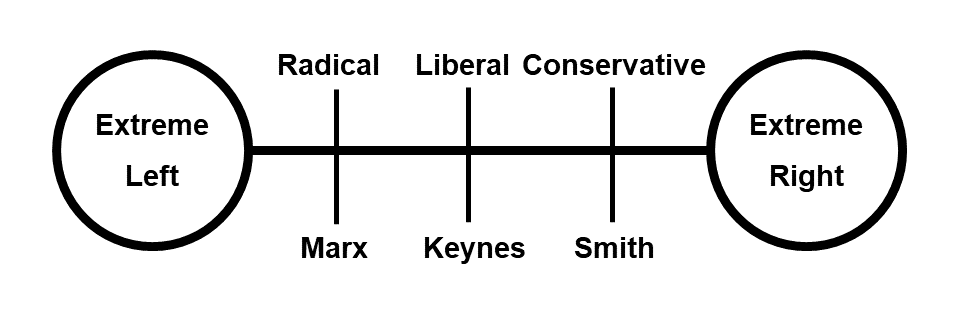

First, I reject the standard political spectrum, what I call the “pendulum” approach to labeling economists. In the world of competing ideologies, the standard political spectrum has Adam Smith, advocate of laissez faire, on the extreme right; Karl Marx, the radical socialist on the extreme left; and John Maynard Keynes, supporter of big government, in the middle. This pendulum approach is unsatisfactory since it equates Adam Smith with the extremism of Karl Marx and represents Keynes as the golden mean or the middle ground.

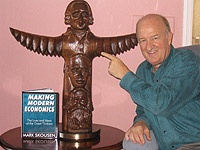

In the introduction to The Making of Modern Economics (and The Big Three in Economics, a shortened popularized version I wrote in 2007), I offered an alternative by creating the “Totem Pole of Economics,” where economists and their theories are measured by their impact on economic freedom and growth. In this ranking, Adam Smith is on top, followed by Keynes, and Marx is “low man” on the Totem Pole of Economics. After the book was published, I commissioned a Florida woodcarver, James Sagui, to carve the totem pole of economics, which now stands in my living room in my house in New York.

Second, I added some important new figures in the history of economics. I devoted a whole chapter (2) to the French laissez faire school, with major sections on J. B. Say and Say’s law of markets; Frederic Bastiat; and Alex de Tocqueville (who had a surprising lot to say about economic ideas and behavior in his Democracy in America).

I am also happy with how Chapter 9, “Go West, Young Man: Americans Solve the Distribution Problem in Economics,” turned out, where I was able to find singular American economists who advanced the development of the factors of production — Henry George on land, John Bates Clark on labor, and Frank Fetter on capital.

Especially novel, I think, is chapter 10, in the middle of the book. It is entitled “The Conspicuous Veblen vs. the Protesting Weber: Two Critics Debate the Meaning of Capitalism.” It follows the success of the marginalist revolution that advanced the Adam Smith model and established “neo-classical” economics as a formal science. Heilbroner and other historians highlighted the sociology of Thorstein Veblen, a major American critic of “neo-classical” economics without providing a counterweight. My middle chapter juxtaposes the ingenious work of Max Weber, the German sociologist who offered a spirited defense of “rational” capitalism. The two sociologists Veblen and Weber served as a perfect counterbalance.

Third, Making restored in the history of ideas how the central role the Austrian school, led by Carl Menger, played in the marginalist revolution and corrected the defects in Adam Smith’s model — his value, long-run cost, and distribution theories that Rothbard complained about. The title of chapter 7 was “Out of the Blue Danube: Menger and the Austrians Reverse the Tide.”

The Making of Modern Economics also broke new ground by publishing a hundred illustrations, portraits, and photographs, and offered details and little-known anecdotes about the lives and ideas of the economists and political thinkers (thanks to several new tell-all biographies). I’ve introduced readers to a variety of subjects and individuals not normally covered in histories, such as Marxist liberation theology. The book records the lives and ideas of important economists often ignored in other histories, such as Montesquieu, Ben Franklin, J. B. Say, Frederic Bastiat, Friedrich List, Herbert Spencer, Ludwig von Mises, Knut Wicksell, Philip Wicksteed, Max Weber, Irving Fisher, Roger Babson, Frederick Taylor, A. C. Pigou, Joan Robinson, Paul Sweezy, Paul Samuelson and Murray Rothbard. My textbook has clever chapter titles and musical selections reflecting the spirit of each major thinker. Students in particular have found these features unique and entertaining. (In fact, no previous history of thought contained any pictures at all.)

For a sample of funny and unusual anecdotes about economists, and the chapter titles, go to http://www.mskousen.com/economics-books/the-making-of-modern-economics/

My History Published on a Special Day

When I finished the manuscript, I submitted it to several publishers. M. E. Sharpe of New York was a surprising choice, because they are well-known to be publishers of radical works by Marxists, socialists, and social democrats. Why would they be interested in publishing a book by a free-market libertarian? Sean Culhane, my editor at ME Sharpe, told me frankly, “Because after the collapse of the Soviet model radical books don’t sell like they used to.” I also believed that having the book being published by a non-conservative/non-libertarian publisher would be a good way to get exposure to a wider audience of students, teachers, and readers.

Every book has a “pub date,” as they call it in the media — the official release date for a book. Mine is special. The manuscript took longer than expected to get published, and went through numerous editing processes and reviews by anonymous referees assigned by the publisher. Finally, the book came out with the official pub date of March 8, 2001. For some reason, March 8 sounded familiar, but I couldn’t put my finger on it. Then it dawned on me: March 8 is the day in 1776 that The Wealth of Nations was published in London!

Given that Adam Smith is the heroic figure of my book, I felt especially honored by this coincidence. (I also had the opportunity of delivering a lecture on Adam Smith on the anniversary of his death, July 17, 2005, on a cruise ship circling the United Kingdom but now docked near Edinburgh.)

Most books are dedicated to an individual, and in my case, I felt that the catalyst behind the work was my uncle W. Cleon Skousen. So I dedicated the book to him.

Positive Responses to the First Edition

For the book jacket, I asked a variety of friends to write blurbs, and received a number of favorable comments, such as the following. From Milton Friedman: “Lively and accurate, a sure bestseller.” From Douglas Irwin of Dartmouth College: “The Making of Modern Economics is the most interesting and lively books on the history of economic thought ever written.” From David Colander, Middlebury College and an author of a history of thought himself: “Entertaining and mischievous, like the author himself.” From Greg Mankiw, Harvard: “Provocative, engaging, anything but dismal.” From Richard Swedberg, the top sociologist at Cornell University: “One of the most original books ever published in economics.” From Richard Ebeling, long-term economics professor at Hillsdale: “One of the most readable ‘tell-all’ histories ever written.” From Steven Kates, former chief economist, Australian Chamber of Commerce, and now a professor at RMIT in Melbourne: “I couldn’t put it down! Humor permeates the book and makes it accessible like no other history. It will set the standard.”

The Ayn Rand Institute lists the MME on the “Top Ten MUST Read Books in Economics,” second only to Henry Hazlitt’s “Economics in One Lesson.”

Mike Sharpe, the publisher and a social democrat, asserted that my work will eventually replace Robert Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers as the most popular history of thought in the classroom. If only!

I was most worried about the reaction of Mark Blaug, the premier historian and author of the classic work, “Economic Theory in Retrospect.” In a handwritten letter, he began by saying that I probably wouldn’t like what he had to say, but then went on to state that the author “tells a story rarely told….I find the book extreme, but is unputdownable — try it and see.” I believe he created a new word for my book.

History of thought books are notoriously dry, especially with regard to the personalities of the economists (virtually non-existent). That’s why many testimonials mentioned the lively nature of the biographies in the book. As Richard Vedder (Ohio University) states, “Mark’s book is a glorious exception to dry history of thought books.”

When the book first came out, the Cato Institute sponsored a book event, with Peter Boettke (George Mason University) commenting, “Skousen gets the story ‘right’ and does it in an entertaining fashion without dogmatic rantings.”

Student responses were the most gratifying. Roger Garrison (Auburn University) reported, “My students love The Making of Modern Economics! Mark Skousen makes the history of economics come alive like no other textbook.” And Ken Schoolland (Hawaii Pacific University) wrote that the book is “the most fascinating, entertaining and readable history I have ever seen. My students love it.”

Business leaders have also enjoyed the book. John Mackey, CEO of Whole Foods Market, read the audio book (published by Blackstone Audio). “Mark’s book is fun to read on every page,” he said. “I have read it three times, and listened to it on audio tape on my summer hike. I love this book and have recommended it to dozens of my friends.”

Academic Reviews

The first edition of The Making of Modern Economics was never reviewed by any of the major academic journals, including the journals that specialize in history of thought, such as the History of Political Economy (HOPE) and the History of Economics Society.

Nor was it reviewed, to my knowledge, by any free-market journals, such as the Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics (published by the Mises Institute) or Review of Austrian Economics (edited by Peter Boettke at George Mason University), even though the text had three chapters on Austrian economists, and was a bold new approach to the history of thought.

A few years after publication my book started getting some notoriety. It was reviewed by the late Bernie Saffran, who taught at Swarthmore College and was the well-respected editor of “For Further Reading” in the Journal of Economic Perspectives. He wrote that it was “lively…amazing…good quotations!”

And in 2009 the American Library Association gave the 2nd edition of my work the Choice Book Award for Academic Excellence.

And Now for the Mixed and Negative Reviews

Least the reader think I’m only cherry picking the good reviews, let me now mention the mixed and negative review. After the first edition came out, it was attacked by Marxists, Keynesians and even a few Austrians. It was pulled from the library shelves of the University of Philippines, a hotbed of Marxism; censored by Keynesians at Columbia University; and blacklisted at the Mises Institute.

Surprisingly, Foreign Affairs reviewed it. The reviewer both loved and hated the book. It was, he said, “both fascinating and infuriating…engaging, readable, colorful.”

David Gordon, editor of The Mises Review, also gave it a mixed review. “Though the book reads well, I find myself compelled to issue a warning. The book is a disaster.” I suspect that Gordon was not happy that I made Adam Smith the hero of the book. I also gave high marks to Milton Friedman for advancing free-market economics in the 20th century. Under the influence of Rothbard, the Mises Institute was highly critical of both Adam Smith and the Chicago school of Friedman.

I’m sure David Gordon and other members of the Mises Institute would be surprised to learn that Ludwig von Mises himself was a big fan of Adam Smith.

Marxists Ban My Book in the Philippines

It wasn’t long before the Marxists discovered my book. One Marxist on Amazon.com stated, “This book stinks! A shallow polemic of an extreme laissez-faire proponent.”

In the early 2000s, I sent a few copies to Mark Tier, a long time Aussie friend who had moved to the Philippines, and he donated a copy to the University of the Philippines, a hotbed of Marxism. A student read it and was so taken with chapter 6, “Marx Madness Plunges Economics Into a New Dark Age,” that he typed the entire chapter into an email and sent it around to his fellow students and his teacher. At the time the Marxist radicals were inviting sympathetic students to attend some revolutionary meetings in the hills around campus. But when they read chapter 6 of my book, they stopped going to the meetings, and even his teacher was converted to free-market economics. It made the Marxists on campus so mad that they had The Making of Modern Economics removed from the library’s bookshelves. (I understand that the ban was temporary and the book has been placed back on the library shelf.)

The Chinese translation also had trouble with chapter 6 on Marx. When I received a copy of the Chinese translation, I asked a Chinese economist to tell me if the chapter title was positive or negative. “Oh, very positive,” he said. “It says ‘Karl Marx and Classical Economics’” — a far cry from the actual title, “Marx Madness Plunges Economics into a New Dark Age”! However, the Chinese economist told me that the rest of the chapter was accurately translated.

The latest translation (actually “The Big Three in Economics”) is in Arabic. The designer of the cover must not have read the book, because the artist has Marx dominating Smith and Keynes.

How “Making” Landed Me a Position at Columbia University

My history of economics even landed me a position at Columbia University. Here’s the story: When I was president of the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) in 2001-02, I contacted William F. Buckley, Jr., the founder of National Review and a friend, to see if we could get together. We decided on lunch at his home in Stamford, Connecticut, in the Spring of 2002. My wife joined me and we had a delightful time as he gave us a tour of his waterfront home. After lunch, he showed us his home office located in his garage, including an entire shelf of Buckley books. He said I could pick any book on the shelf and he would autograph it. I chose one of his sailing books, all of which I had read.

Almost as an afterthought, I gave him in turn a copy of The Making of Modern Economics, and we left.

I didn’t think anything of it until a month later a review of the book appeared in National Review. It was totally unexpected. Buckley wrote that he loved the book and thought it would make an excellent gift to college students.

A few weeks later I received a telephone call from John Whitney, a veteran business leader and popular professor at the Columbia Business School. He specialized in turnarounds. He said that based on Buckley’s review, he had bought and read my book and liked it so much he wanted to meet me. After we had lunch, he invited me to give a guest lecture at Columbia Business School. It was intimidated but he and the students liked my presentation so much that he told me, “Mark, I’ve decided to retire from Columbia and I’d like you to take my place.” I was honored, and so the process began. I had Milton Friedman write a letter of recommendation to the dean, and Professor Whitney finally convinced the Keynesian chair of the department, Ray Horton, to give me a try. I taught economics at Columbia in 2004-05, all thanks to John Whitney…and Bill Buckley. In the business course, I used The Making of Modern Economics but the department chairman saw my free-market history as a threat to a similar class he taught, “Modern Political Economy,” and my course was summarily discontinued.

Buckley, by the way, continued to be a fan of my work. In 2005, I ran into him on a cruise around the British Isles in honor of the 50thanniversary of National Review and the 25th anniversary of my newsletter, Forecasts & Strategies. He surprised me when he told me privately, “It’s my favorite book on economics. I champion your book to everyone. I keep it by my bedside and refer to it often.”

The Second Edition (2009)

After the financial crisis of 2008, it became apparent that The Making of Modern Economics needed a second edition. I added new material in several chapters, especially at the end with space devoted to the financial crisis and the work of imperfect markets by Joseph Stiglitz, who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 2001. Given the perception that capitalism failed in 2008-09 and was on the defense, I felt it necessary to change slightly the title of chapter 17 to “Dr. Smith Goes to Washington: The Near Triumph of Market Economics.”

The second edition won the Choice Book Award for Outstanding Academic Title, and has gone on to become a popular history of thought textbook, now rivaling Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers. It has been translated into six languages–Spanish, Turkish, Mongolian, Polish, Arabic, and Chinese (twice).

Third Edition (2016)

When M. E. Sharpe was bought out by Routledge Publishers in late 2014, the Routledge editors thought it appropriate to update the MME with a third edition. New sections were added on the “Invisible Hand, Central or Marginal?”, liberation theology, and a major rewrite of the final chapter 17 with new sections on the financial crisis of 2008-09, inequality, the “austerity vs. stimulus” debate, market imperfections, and “Hayek vs. Keynes Redux” and breakthroughs in market design and other microeconomic contributions.

Appropriately, the new statue of Adam Smith, located on High Street in Edinburgh, graces the cover of the third edition, a fitting tribute to the father of modern economics.

How to Order Your Copy of “The Making of Modern Economics”

For only $35

A qualify paperback third edition of The Making of Modern Economics: The Lives and Ideas of the Great Thinkers, published by Routledge, is now available at a substantial discount. The retail price by the publisher and Amazon is $45.99, but you pay only $35 postpaid if you order through Ensign Publishing, toll-free 1-866-254-2057.

All copies are shipped free inside the United States, and autographed by the author. (For orders going to Canada and other foreign countries, call Harold at Ensign Publishing for additional shipping costs.)

The Making of Modern Economics is also available on Kindle, or audio book, at Amazon.com.

[1] The possible exception is The Roots of Capitalism, by John Chamberlain (1965), now out of print.

[2] For more information, see my paper, “The Centrality of the Invisible Hand,” presented on January 31, 2012, at Hillsdale College.

[3] Ludwig von Mises, “Why Read Adam Smith Today,” in Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (Regnery, 1998), pp. xi-xiii.