- China is evolving from a current account surplus to deficit country

- Increased domestic consumption and dis-saving by an ageing population drives the trend

- Lower investment in developed countries may be assuaged by major central banks

- Emerging and Frontier markets will struggle to replace China’s long-term investment

China has slowly seen its current account surplus dwindle. In large part, this change from surplus to deficit has been driven by demographic forces. As a result of China’s previous ‘one child’ policy, enacted in 1979, the country is destined to grow old before it becomes rich, at least by Western standards. The one child policy has now been relaxed but, as yet, only a tiny percentage of parents have applied to have a second child. What does that mean for the prospects for Chinese assets and what might be the implications for the asset markets of its trading partners?

Demographic disaster need not be the end-game for China, writing back in May 2015 for CFR’s Foreign Affairs – China Will Get Rich Before It Grows Old – Baozhen Luo speculated that: –

If China continues to meet its demographic challenge head-on, it might yet be able to grow old and rich at the same time.

During the last 70 years China’s average life expectancy has risen from 35 to 75 whilst its fertility rate has collapsed – it is now lower than France or the US. On current trend, 30% of China’s population will be over 60 by 2050 as the median age rises to 46 years. Nonetheless, this powerful trend has been tempered by rising female labour-force participation and educational improvements which have boosted productivity. Another factor, helping to offset the impact of ageing, is the rising number of beyond retirement age workers. These elements, though significant, remain insufficient to stop China’s working age population declining, according to the National Bureau of Statistics it peaked at 941 million in 2011.

Other emerging economies, especially India and Indonesia, continue to reap the demographic dividend, capturing market share in low-tech, labour intensive industries. Chinese exports have not vanished, however, India’s trade deficit with China hit US$62bln in 2017, even in the face of escalating Chinese labour costs. Cogniscent of its dwindling competitive advantage in unskilled labour, China has concentrated in adding value through technological investment to raise productivity further. As developed coastal regions become more high-tech, lower cost manufacturing industries have been relocated inland, capitalising on the continued flow of low-cost, unskilled rural workers, migrating to the cities.

China’s leaders are keen observers of the tide, where the country cannot compete in trade, it has become a prominent investor. Its focus has been on neighbouring countries such as Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. It has also made significant strategic investments in resource rich, but economically underdeveloped, countries in regions such as Africa.

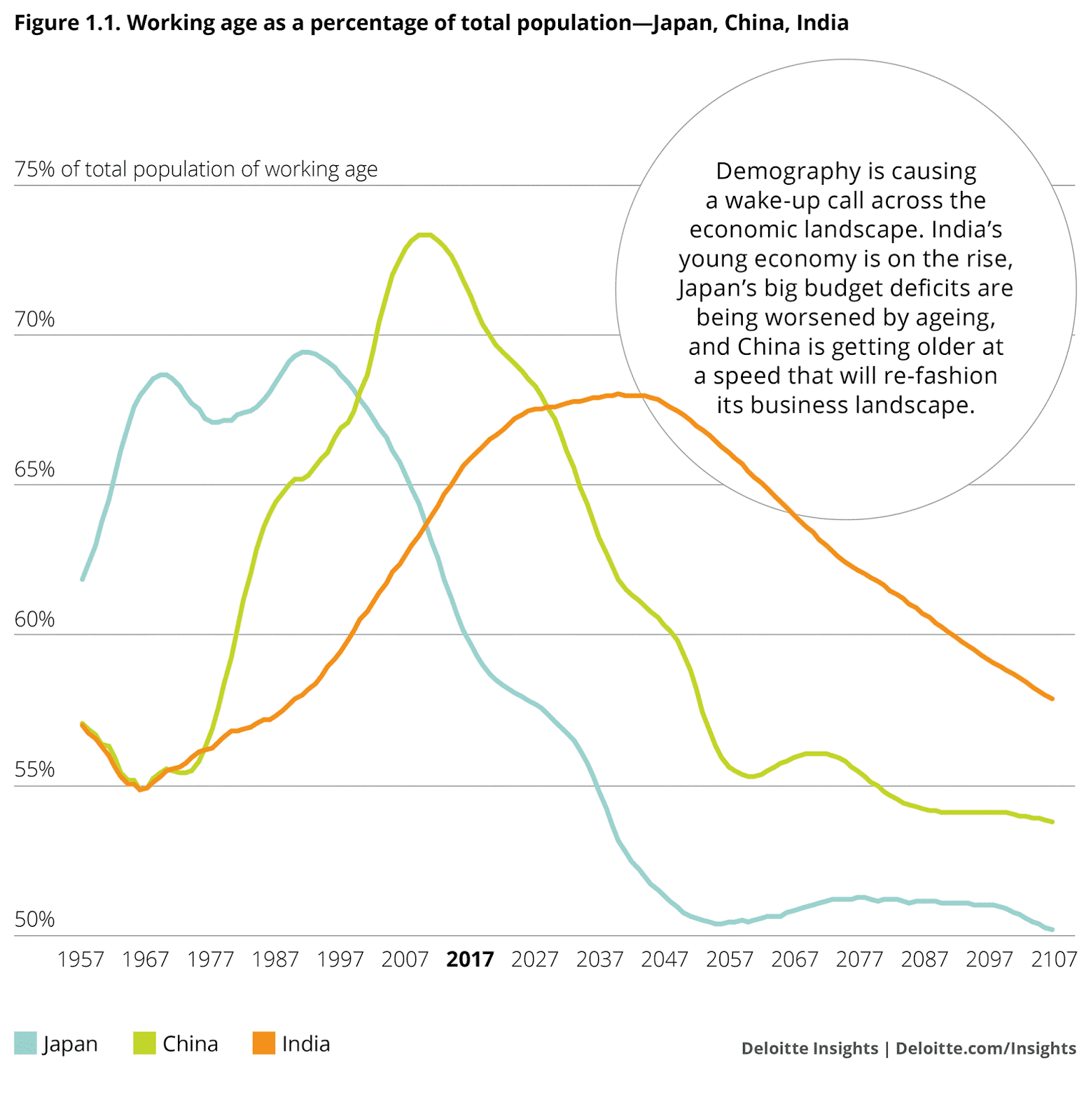

The demographic problems facing China are substantial. Pension deficits are rising, as are healthcare costs, meanwhile China’s high savings rate is finally beginning to diminish. In Deliotte’s Q3 2017 Insights report – Ageing Tigers, hidden dragons – the authors’ discuss a third wave of Asian growth, pointing to India and noting that China’s economic expansion, whilst still the largest contributor to world GDP growth in absolute terms, has been slowing for several years. The chart below shows the steep peak in China’s working age population around 2011; on current trend China’s average age will exceed the US by 2021 and equal that of Japan by 2045: –

Source: Deloitte

During the next decade, India’s working-age population will rise by 115mln: more than half of the 225mln expected increase across Asia as a whole. This is not just a Chinese problem, with the notable exception of Indonesia and Philippines, the ageing problem will also beset the rest of Asia, as the chart below makes clear: –

Source: Deloitte

As for China growing old before it grows rich, this depends on one’s definition. In a recent note, Craig Botham of Schroders – Does it matter if China gets old before it get rich? Makes the following observations: –

Current GDP per capita is a little under $10,000, against $40,000 in Japan, and $60,000 in the US. With its current median age, China is the world’s 67th oldest country, and a median age of 45 would make it the 6th oldest country in the world today, which seems a good criteria for being “old” in absolute terms. China hits this age around 2035. Defining “rich” is also difficult, but taking the poorest Western European economy as an example would require GDP per capita of around $20,000. Reaching $20,000 GDP per capita in real terms by 2035 would require annual income growth of nearly 5%, when growth is at 6.5% and slowing. Raising the income threshold to $30,000 would need annual growth of 8%, and $40,000 (modern Japan) would require 10% growth. Achieving US levels of $60,000 would require a herculean 13% rate. It seems highly likely that China will indeed become old before it becomes rich.

China has far to go – and India even further – before they reach the levels of income of the developed nations, but in China’s case, the rebalancing towards domestic consumption is beginning to transform a country which was once the epitome of a mercantilist exporter of manufactures.

Last week saw the publication of a lead article in the Economist – China may soon run its first annual current-account deficit in decades – as the author writes, the implications will be profound. The chart below shows a country in transition, regardless of its record trade deficit with the US: –

Source: The Economist

Ignoring the blip in March 2018, China may run its first current account deficit since 1993 this year. In 2017 the current account surplus was 1.3% GDP, down from 1.8% in 2016. The ratio has been falling steadily from as high of 10% in 2007. To balance the books, the country will need to attract foreign investment; an acceleration in the policy of financial market liberalisation is likely to be embraced. The Economist expresses it like this: –

China’s decades of surpluses reflected the fact that for years it saved more than it invested. Thrifty households hoarded cash. The rise of great coastal manufacturing clusters meant exporters earned more revenues than even China could reinvest. But now that has begun to change. Consumers are splashing out on cars, smartphones and designer clothes. Chinese tourists are spending immense sums overseas. As the population grows older the national savings rate will fall further, because more people in retirement will draw down their savings.

… China will need to attract net capital inflows… has eased quotas for foreigners buying bonds and shares directly… Pension funds and mutual funds all over the world are considering increasing their exposure to China.

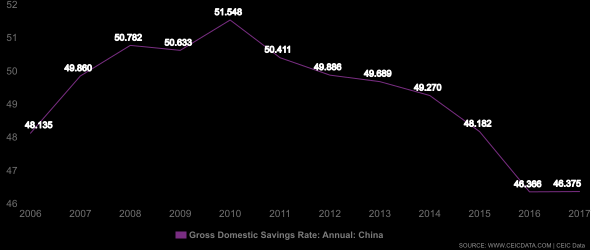

This chart shows the evolution of China’s gross saving rate as a ratio of GDP since 2006: –

Source: CEIC

The savings rate may be in decline but capital market liberalisation is not without risks, many Chinese have managed to extract money from China, despite capital controls; the real-estate markets of Australia, Canada and, to a lesser extent, London and New York, bear testament to this trend. Yet, to attract the substantial foreign investment that will be required, it is important for foreigners to feel confident that they can withdraw their investment. The Chinese authorities risk opening the flood gates. Despite the different conclusions they are likely to draw, Malaysia’s imposition of capital controls during the Asian crisis of 1998 remains fresh in the minds of Chinese officials and institutional investors alike.

Foreign Direct investment may be robust but far more will be needed as trade balances switches sign. February saw FDI in manufacturing rise 12%, whilst investment in high-tech manufacturing grew by a less stellar 9.3%.

For the Chinese authorities, another concern with liberalisation is the potential impact on many state owned enterprises. These heavily indebted behemoths are in a parlous position. Root and branch reform will be required to insure they do not precipitate financial, social and political instability.

The rest of the world will not be immune to the impact of China switching from current account surplus to deficit either. After the Japanese stopped investing their surplus earnings abroad the Chinese took up the gauntlet. Now that the flow of investment from China is diminishing, less economically developed countries, such as those of the African sub-continent, will find their infrastructure investments curtailed and their longer-term interest rates rising. The US Treasury will have to rely more heavily on it central bank to fill the void of Chinese investment dollars, but less developed countries will suffer. Other current account surplus countries will fill the investment void, but, unlike China, which has been investing for the long run, they are less likely to buy and hold over such an extended time horizon.

Conclusions and investment opportunities

China has spent many years sterilising the effect of its current account surplus by increasing official reserves. A large proportion of these reserves have been invested in US Treasuries, although latterly other developed government bond markets have benefitted from a move towards greater reserve diversification on the part of the Peoples Bank of China (PBoC).

As the current account switches sign from surplus to deficit, China will need to attract greater foreign investment to prevent its currency from declining. Relaxing of capital controls will be necessary to support the growing domestic consumption demand of an ageing populous. The risk for China is of greater domestic instability. They fear a flood of landlocked private savings being sent abroad, whilst inward fickle foreign investment offers a poor substitute, driven, as it is, by the need for short-term performance.

The solution to the PBoC’s capital conundrum is to adopt the policy levers favoured by developed nation central banks. Using quantitative techniques they can manage interest rates across the yield curve while Chinese capital markets steadily transform from a side-show into the main attraction. The transition will be uneven but the needs of a semi-affluent, ageing society are even more pressing than those of the deficit nations of the affluent developed world. Unlike Japan, whose international investments took the form of individual retirement savings, China’s external investments have been largely centrally directed. The needs of China’s ageing society, to draw down on savings, requires that the government replace domestic investment with foreign capital. To attract this capital to state owned enterprises will require more than just the relaxation of capital controls, it will require root and branch reform of these enterprises.

As China moves from an economic model of Communism with beauty spots to Capitalism with warts its outlook will inevitably become shorter-term, making asset markets will more volatile. The influence of its central bank will increase dramatically, as it adopts the policies of its developed nation peers. The overall pattern of international capital flows will become more fickle, to the detriment of less developed countries.