Interest Rates, Global Value Chains and Bank Reserve Requirements

- Global Value Chains have suffered since 2009

- Despite low interest rates, financial costs remain too high

- Bank profitability has not recovered, yet banks are still too big to fail

In a recent speech, Hyun Song Shin, Head of Research at the BIS, discussed – What is behind the recent slowdown? The speech focused on the weakening of global value chains (GVC’s) in manufactured goods. The manufacturing sector is critical, since it accounts for 70% of global merchandise trade: –

During the heyday of globalisation in the late 1980s and 1990s, trade grew at twice the pace of GDP. In turn, trade growth in manufactured goods was driven by the growing importance of multinational firms and the development of GVCs that knit together the production activity of firms around the world.

The chart below reveals the transformation of the world economy over the past 17 years: –

Source: BIS, X Li, B Meng and Z Wang, “Recent patterns of global production and GVC participation”, in D Dollar (ed), Global Value Chain Development Report 2019, World Trade Organization et al.

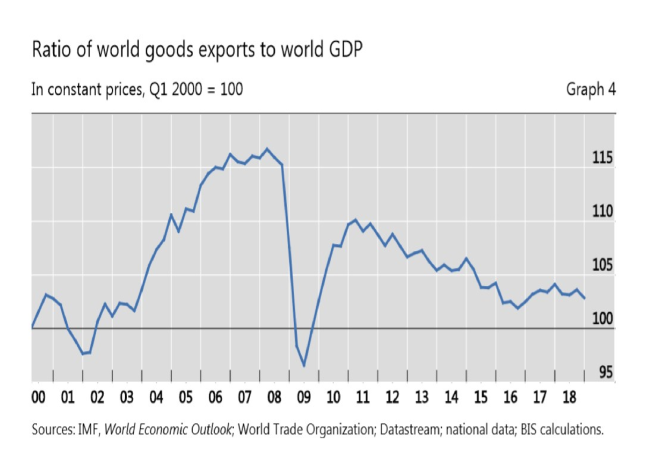

Hyun’s next chart tracks the sharp reversal in the relationship between world trade and GDP growth as a result of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC): –

Sources: IMF, World Economic Outlook; World Trade Organization; Datastream; national data; BIS calculations

The important point, highlighted by Hyun, is that the retrenchment in trade occurred almost a decade before the trade war began. China, growing at 6% plus, has captured an increasing share of global trade at the expense of the developed nations, most notably the US. Europe went through a similar transition during the second half of the 19th century, as the US transformed from an agrarian to an industrial society.

Returning to the present, supporting GVCs is capital intensive. Historically low interest rates have allowed these chains to flourish, but the recent reversal of interest rate policy by the Federal Reserve has caused structural cracks to emerge in the edifice. The BIS describes the situation for multi-national manufacturing firms in this way (the emphasis is mine): –

…firms enmeshed in global value chains could be compared to jugglers with many balls in the air at the same time. Long and intricate GVCs have many balls in the air, necessitating greater financial resources to knit the production process together. More accommodative financial conditions then act like weaker gravity for the juggler, who can throw many more balls into the air, including large balls that represent intermediate goods with large embedded value. However, when the shadow price of credit rises, the juggler has a more difficult time keeping all the balls in the air at once.

When financial conditions tighten, very long and elaborate GVCs will no longer be viable economically. A rationalisation of supply chains through “on-shoring” and “re-shoring” of activity towards domestic suppliers, or to suppliers that are closer geographically, will help reduce the credit costs of supporting long GVCs.

It is interesting to note the use of the phrase ‘shadow price of credit,’ this suggests that concern about the intermediation process by which changes in the ‘risk-free’ rate disseminate into the real-economy. In a 2014 study, the BIS Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS) found that 65% of world trade is still financed through ‘open account financing’ or through the buyer paying in advance. For GVC’s, short-term US interest rates matter, especially when 80% of trade finance is still transacted in the US$. Even when rates reached their nadir, banks were reluctant to lend at such favourable terms as they had prior to the GFC. The recent rise in short-term interest rates has supported the US$, accelerating the reversal in the trade to GDP ratio.

A closer investigation of bank lending since the GFC reveals structural weakness in the intermediation process. Since 2009, at the same time as interest rates fell, bank capital requirements rose. The impact of this fiscal offsetting of monetary accommodation can be seen most clearly in the global collapse the velocity of circulation of money supply: –

Source: Tom Drake, National Data, Macrobond

The mechanism by which credit reaches the real economy has been choked. Banks have gradually repaired their balance sheets, but the absurd incentives, such as the inducement to purchase zero risk-weighted government debt rather than lending to corporates, have been given fresh impetus through a combination of structurally higher capital requirements and lower interest rates.

In their January 2018 publication – Structural changes in banking after the crisis – the BISexamines how credit intermediation has changed (the emphasis is mine): –

The crisis revealed substantial weaknesses in the banking system and the prudential framework, which had led to excessive lending and risk-taking unsupported by adequate capital and liquidity buffers…

There is no clear evidence of systematic and long-lasting retrenchment of banks from credit intermediation. The severity of the crisis was not uniform across banks and systems. Weaker banks cut back credit more strongly, and riskier borrowers saw their access to credit more tightly curtailed. In the immediate aftermath of the crisis the response of policymakers and bank managers was also differentiated across systems, with some moving more decisively than others to address the problems revealed. Bank credit has since grown relative to GDP in most jurisdictions, but has not returned to pre-crisis highs in the most affected countries, reflecting necessary deleveraging and the unwinding of pre-crisis excesses. While disentangling demand and supply drivers remains a challenging exercise, the evidence gathered by the Working Group does not point to systematic change in the willingness of banks to lend locally. In line with the objectives of post-crisis reforms, lenders have become more sensitive to risk and more discriminating across borrowers…

The last two sentences appear to contradict, but measuring of loan quality from without is always a challenge. The authors’ continue to perceive credit quality and intermediation, through a glass darkly (once again, the emphasis is mine): –

If anything, the shift towards commercial banking activities suggests that banks are putting more emphasis on lending than trading activities. Still, given the range of changes in the banking sector over the past decade, policymakers should remain attentive to potential unintended “gaps” in credit to the real economy. Legacy asset quality problems can be an obstacle to credit growth. Excessive pre-crisis credit growth left a legacy of problem assets, especially high levels of NPLs, which continue to distort the allocation of fresh credit in several countries…

Persistently high NPLs are likely to lead to greater ultimate losses, impede credit growth and distort credit reallocation, potentially incentivising banks to take on more risk….

Again, the evidence seems to be contradictory. What is different between the cyclical patterns of the past and the current state of affairs? The tried and tested central bank solution to previous crises, stretching all the way back to the 1930’s, if not before, is to cut short-term interest rates – regardless of the level of inflation. The yield curve steepens sharply and banks rapidly repair their balance sheets by borrowing short-term and lending long-term. In the wake of the GFC, however, rates declined yet the economy failed to respond to the stimulus, at least in part, because the central banks accommodative actions were being negated by the tightening of regulatory conditions. Collectively the central banks and the national regulators were robbing Peter to pay Paul. The result (please pardon my emphasis once more): –

Post-crisis bank profitability has remained subdued. This reflects many factors, including bank-specific drivers (eg business model choices), cyclical macroeconomic drivers (eg low growth and interest rates) and structural drivers that will have a more persistent impact. An example of this latter group includes regulatory reforms that have implied lower leverage and the curbing of certain higher risk activities, and a reduction of implicit subsidies for large or systemically important banks…

…all else constant, lower leverage and reduced risk-taking should reduce return on equity. Sluggish revenues have dampened profits and, combined with low interest rates, may have contributed to the slower progress made by some banks in dealing with legacy problem assets…

Sufficient levels of capital are needed for banks to deal with unexpected shocks, and low profitability can weaken banks’ ability to maintain sufficient buffers. Banks that lack a steady stream of earnings to repair their capital base after an unexpected loss will have to rely on fresh equity issuance. Yet, markets are usually an expensive source of capital for banks, when accessed under duress….

In this scenario banks have an incentive to extend and reschedule zombie loans in order to avoid right-downs. Companies which should have been forced into administration linger on, banks’ ability to make new loans is curtailed and new ventures are starved of cash.

The BIS go on to make a number of suggestions in order to deal with low bank profitability and the problem of non-performing legacy assets: –

If overcapacity is a key driver of low profitability, institutional barriers to mergers must be reviewed and exit regimes applied. If the problem lies with legacy assets (such as NPLs), these should be fully addressed, which might entail a dialogue between prudential authorities and other policymakers (eg those in charge of mechanisms dealing with insolvency)…

The exit of financial institutions might be politically costly in the short run, but may pay off in the longer term through more stable banking systems, sounder lending and better allocation of resources. The implicit subsidisation of non-viable business models might have lower short-term costs but could lead to resource misallocation. Similarly, any assessment of consolidation trends needs to take into account potential trade-offs between efficiency and stability, as well as examine the nature and impact of barriers to exit for less profitable banks.

These suggestions make abundant sense but that is no guarantee the BIS recommendations will be heeded.

I am also concerned that the authors’ may be overly optimistic about the resilience of the global banking system: –

Compared with the pre-crisis period, banks are better capitalised and have lower exposure to liquidity and funding risks. They have also reduced activities that contributed to the build-up of vulnerabilities, such as exposure to high-risk assets, and excessive counterparty risk through OTC derivatives and repo transactions, among others. That said, given that markets have not yet evolved through a full financial cycle, bank restructuring efforts remain under way. In addition, as many relevant reforms have not yet been fully implemented, it is too early to assess their full effect.

Thankfully the BIS outlook is not entirely rose-tinted, they do acknowledge: –

…some trends in banking systems that we have observed since the crisis, such as the decline in wholesale funding, might be affected by unconventional monetary policy and may not persist. Success in addressing prior problems does not guarantee that banks will be able to respond to future risks…

Problems of bank governance and risk management contributed to the crisis and have been a key focus of reform. Given that the sources of future vulnerabilities are hard to predict, banks need to have robust frameworks of risk governance and management to identify and understand emerging risks and their potential impacts for the firm.

The BIS choose to gloss over the fact that many banks are still far too big to fail. They avoid discussing whether artificially low interest rates and the excessive flatness of yield curves may be contributing to a different breed of systemic risk. Commercial banks are for-profitinstitutions, higher capital requirements curtail their ability to achieve acceptable returns on capital. The adoption of central counterparties for the largest fixed income market in the world, interest rate swaps, whilst it reduces the risk for individual banking institutions, increases systemic risk for the market as a whole. The default of a systemically important central counterparties could prove catastrophic.

Conclusions and investment opportunities

The logical solution to the problem of the collapse of global value chains is to create an environment in which the credit cycle fluctuates less violently. A gradual normalisation of interest rates is the first step towards redemption. This could be accompanied by the removal of the moral hazard of central bank and government intervention. The reality? The societal pain of such a gargantuan adjustment would be protracted. It would be political suicide for any democratically elected government to commit to such a meaningful rebalancing. The alternative? More of the same. Come the next crisis central banks will intervene, if they fail to avert disaster, governments’ will resort to the fiscal spigot.

US interest rates will converge towards those of Europe and Japan. Higher stock/earnings multiples will be sustainable, leverage will increase, share buy-backs will continue: and the trend rate of economic growth will decline. Economics maybe the dismal science, but this gloomy economic prognosis will be quite marvellous for assets.