by Elisabeth Krecké

Global debt has surged spectacularly in recent years and now stands at an all-time high of more than 322 percent of world output. The growth of public debt has played a substantial role in that process. In many cases, the debt amassed by governments around the world is a policy response to the 2008 financial crisis and ensuing recession. Yet many economists believe these liabilities have become a ticking time bomb, not least because – contrary to popular belief – sovereigns can go bankrupt.

Such bankruptcies occur more often than one might think, as former International Monetary Fund (IMF) chief economist Kenneth Rogoff, and co-author Carmen Reinhart, show in a prominent historical analysis(This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly). Their report casts light on a myriad of bank panics and government defaults, from the early Middle Ages to the 2007 subprime debacle. When their study was published in 2009, the worst was still to come, notably in Europe.

Europe’s Achilles’ heel

The original idea behind the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) was to rely on market discipline to provide incentives for governments to engage in sustainable fiscal policies. The Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) formally prohibits monetizing debt (i.e., inflating away domestic debt in local currency by printing money). It also forbids the European Central Bank (ECB) from bailing out defaulting countries.

As a consequence, EMU member states are exposed to credit risk in a way other advanced economies are not. When eurozone governments contract debt, they necessarily issue their bonds in euros – the bloc’s common currency on which, individually, they cannot exert any control. Thus they cannot credibly guarantee that bondholders will systematically be paid as bonds reach maturity. This threat alone is supposed to prevent governments from fiscal irresponsibility. That hope turned out to be a pipe dream.

When the global financial crisis hit, what was thought to be the EMU’s strength was suddenly revealed as a major weakness. Given the EMU’s specific configuration, sovereign debt can lose its status as a safe investment, sometimes in the blink of an eye. This is what happened to Greece in late 2009, after revelations of its underreported debt levels and budget deficits led to severe market sanctions. As panicking investors dumped large amounts of Greek bonds, yields shot up, and the country soon had to face dramatic rises in borrowing costs, which in turn exacerbated its debt burden.

The Greek ordeal clearly showed how a liquidity crisis can arise when market participants fear that a government might be hit by such a crisis. These situations are aggravated when the country’s banking sector is close to collapse.

Doom loops

During the Greek and subsequent European debt crises, which peaked between 2010 and 2012, the euro area experienced another painful phenomenon: the threat of debt contagion via a dreaded “domino effect” – triggered precisely by a cocktail of high public debt (downgraded to junk status), rapidly rising yield spreads in government securities and the failure of financial institutions in some member states. The viability of the euro, the most ambitious project of European integration, was put at risk for the first time in the currency’s young history.

As Greece, Portugal, Spain, Ireland and Cyprus were caught up in the spiral of inextricable bank-state ties (the so-called “doom loop”), all other eurozone countries, one after the other (with Italy on the front line), looked like they could be sucked into the debt vortex. They avoided that danger by collectively contributing to a series of multibillion-euro rescue programs to support those in distress, via the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). In doing so, however, they also worsened their own debt situations.

For Greece alone, the EFSF and ESM together paid out about 204 billion euros. The ESM now holds more than half of the country’s public debt. On the brink of a forced exit from the eurozone, Greece needed three successive bail-out packages. The last of these ended in August 2018.

Some describe the crisis management performed by the European troika – the ECB, the IMF and the European Commission – as a failure. This is mostly because the harsh austerity measures that were implemented as a condition of the loans Greece was granted caused disastrous long-term consequences for the Greek population. Moreover, the rescue funds have been criticized for breaking the TFEU’s “no bail-out” clause. To many observers, they look like an “EU fiscal system by the back door.”

Slippery slopes

Today, despite the many lessons learned from a decade of cascading crises, public debt continues to rise worldwide. Japan currently holds the record with a public debt-to-GDP ratio of almost 240 percent. However, in contrast to EMU countries, which are deprived of monetary policy flexibility, the Bank of Japan cannot run out of money.

High sovereign debt remains a major vulnerability for several euro area economies. In Greece, still the second-most indebted nation in the world, the ratio peaked at around 185 percent in 2018, and has slightly decreased since. For comparison, it oscillated between 146 percent and 179 percent during the worst of the Greek crisis.

No less worryingly, in Italy, the eurozone’s third-largest economy, government debt has risen continuously since 2012 and ballooned to 138 percent of GDP in 2019. It now exceeds 2.3 trillion euros. Crucially, the ESM can mobilize a total of 700 billion euros to help an economy in trouble – less than a third of Italy’s colossal debt.

In other EU countries, public debt will continue to grow faster than economic output. According to the IMF’s Global Debt Database, the figures for Portugal (120.13 percent), Cyprus (102.53 percent) and Belgium (102.03 percent) cause the most worry, but the debt levels of France (98.39 percent) and Spain (97.09 percent) also spark concern. Policymakers who promise further increases in government spending and redistribution, rather than a reduction of public debt, exacerbate these apprehensions.

These countries have failed to put their finances in order after the global financial crisis, the European Commission again pointed out last November during the presentation of the European Semester’s Autumn Fiscal Package. Fourteen of the 27 EU member states are either unable or unwilling to respect the 60 percent debt-to-GDP limit imposed by the bloc’s Stability and Growth Pact – that is, they are noncompliant with the EU’s basic rules for fiscal soundness.

The good, the bad, the ugly

“Not all debt is the same,” the IMF rightly recalled in a conference announcement this past November. It makes a distinction between the “good,” the “bad” and the “ugly” debt.

Debt spent wisely – on the expansion of productive investment for instance (such as infrastructure, education, health and other public goods) – is normally a driver for continued economic growth, the IMF argues. On the contrary, debt merely spent on social welfare and driven by electoral or ideological concerns can hinder a country’s economic performance. For example, when Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez pledged to spend more and raise taxes, the offer was likely designed to please the far-left Podemos members of his recently formed, highly fragile, coalition government.

A new financial crisis could hit southern European nations hard, not least because their high public debt levels would make it difficult for them to conduct countercyclical policies. Entering into troubled times with a weak fiscal position risks aggravating the depth and duration of the resulting recession, thereby exacerbating national vulnerabilities.

Moreover, this time, intergovernmental solidarity may no longer stand ready to pay for some member states’ persistent lack of fiscal responsibility. Political willingness to complete the EMU’s implementation appears to have lost momentum.

In July 2012, then-ECB President Mario Draghi pledged to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro, a move that successfully stabilized sovereign bond markets. It is uncertain whether a similar pledge would suffice the next time financial turmoil rears its head.

Changing narrative

Excessive public debt is “probably bad,” but “not catastrophic,” argues Olivier Blanchard, one of the world’s most respected economists.

In a much-discussed paper, presented in January 2019 at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association (of which he was the outgoing president), Mr. Blanchard makes two surprising assertions. First, as long as growth rates exceed interest rates, the issuance of public debt virtually has no fiscal costs. That is, it does not imply distortionary tax rises in the future. Second, welfare costs may also be much smaller than is frequently assumed, as debt is rolled over from one generation to the next.

Without going as far as to advocate for further increases in public debt, the former IMF chief economist (who some had considered a possible successor to Mr. Draghi at the ECB) urges us to fundamentally rethink public debt policies in the current, persistently morose, economic environment. Growth forecasts may be pessimistic, he says, but interest rates can be expected to go even lower in the years and decades to come.

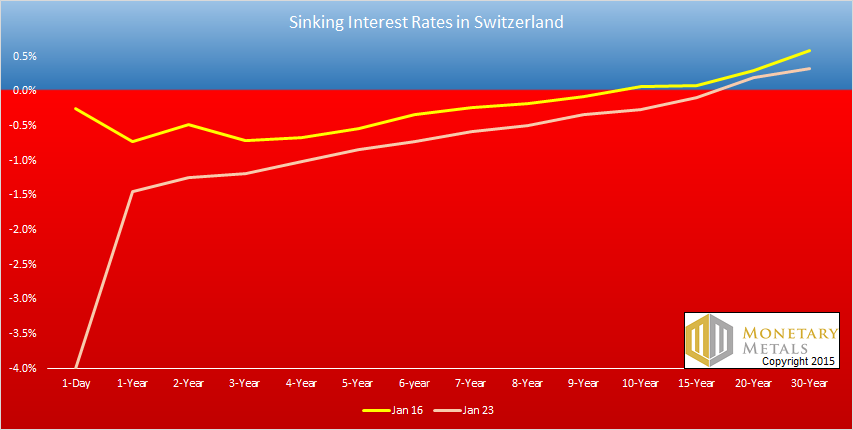

Since the 2008 crisis, the “zero-lower-bound” of interest rates has lost its taboo for central banks. The ECB introduced slightly negative rates for the first time in June 2014, by lowering its deposit rate to -0.1 percent. Today, it stands at -0.5 percent.

Several recent IMF studies have devised strategies for how to enable “deeply” negative interest rates. In Mr. Blanchard’s perspective, if this were to become a feasible option in the short to medium term, the prevailing government debt levels, including in the eurozone, should by no means be considered “too high.”

While current public debt-to-GDP ratios may look “scary,” such numbers are actually not “economically relevant,” Mr. Blanchard further reassures us. Clearly, for him, the “right variable” to consider is not public debt per se, but what he calls the “safe” interest rate (defined as the rate of return obtainable from relatively risk-free investment), as compared with the growth rate.

Market whisperers

For Mr. Blanchard, the key is how markets respond to high public debt levels. The European debt crisis showed how quickly confidence in the sustainability of public debt can plummet and, with it, investors’ estimation of governments’ creditworthiness. As former ECB executive board member Benoit Coeure put it, the perception of public debt in the eurozone, before and after the 2008 crash, shifted from one extreme (“too safe”) to another (“too risky”).

“Imperfect markets,” under the influence of investors’ supposedly flawed risk assessments, are often blamed for playing a critical role in the ratings downgrades that several EMU nations received after the crisis hit. In hindsight, many policymakers believe that if bondholders and rating agencies had not overreacted (in their view), the Greek debt tragedy may only have been half as bad.

Mr. Blanchard cautions that we should beware of what scholars call “self-fulfilling equilibria.” In such situations, investors’ worry over a sovereign potentially defaulting on its debt finally leads to an aggravation of that debt (as the spreads required on that debt can increase interest payments to an extent that can be truly risky), thus validating those fears.

To break such harmful cycles, debt reduction is certainly not the solution, the argument goes. Instead, the public-debt narrative should be changed.

Mr. Blanchard posits that developing sensible arguments to show that high government debt is not as dangerous as the media and credit agencies would have us believe could be a first step toward calming market turmoil. He invites policymakers and their academic advisors to increase efforts to “educate” market participants. In other words, policy should aim to correct bondholders’ biased evaluation of the safety of sovereign debt.

Behind this effort to make high debt levels less frightening, one might identify what economic methodologists call “paternalist” policy. Mr. Blanchard’s recommendation clearly rests on the assumption that high-profile economists know better than investors of what an acceptable level of public debt is.

In this endeavor to reeducate investors and rating agencies, Mr. Blanchard would not mind personally taking the lead. “I’ll do my best,” he wrote recently, without specifying how conveying this information to markets (and the subsequent learning process) should look.

The burning question is of course whether elite economists retelling the story is enough to assure market stability in the long term, in the face of ever-higher levels of public debt.

Elisabeth Krecké is a Professor of Economics at Aix Marseille University, France.