The sudden resignation of Japans Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has led to evaluations of his so-called Abenomics. Many have praised Abe’s aggressive monetary policy because the long shopping list of the Bank of Japan (government bonds, corporate bonds, ETFs and real estate investment trusts) has inflated stock and real estate prices (Shirai 2020; Financial Times 2020). Concerns remain on the fiscal side since Abe’s consumption tax hikes from 5 percent to 8 percent in 2014 and to 10 percent in 2019 are widely seen as a failure (The Economist 2020). Indeed, Abe resolved Japan’s deep-seated fiscal problems only superficially.

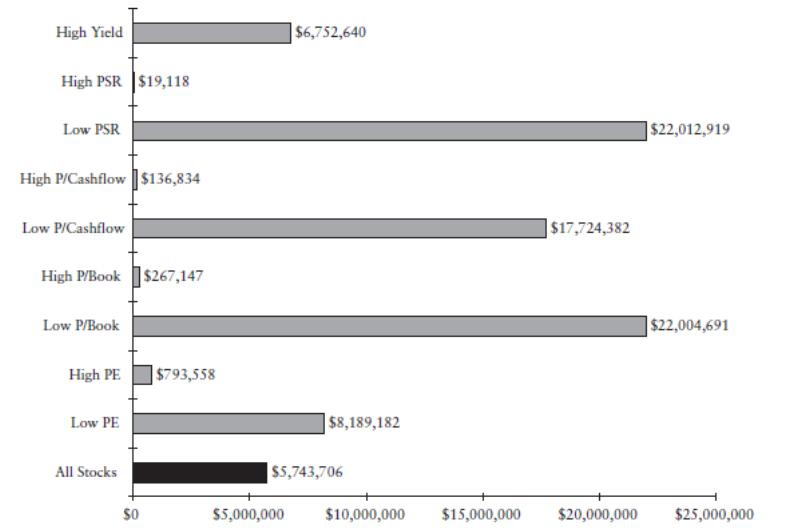

Figure 1: Tax Revenues of Japan’s Central Government

Source: Ministry of Finance, Japan.

The core of the problem is cheap money issued by the Bank of Japan, which had caused a stock and real estate bubble in the second half of the 1980s. While the bubble had inflated tax revenues, its bursting was followed by an unprecedented economic slump during which the corporate and income tax revenues collapsed from 43 trillion yen (approx. 390 billion dollars) in 1990 to 23 trillion yen (approx. 185 billion dollars) in 2012 (Figure 1), when Abe took office.

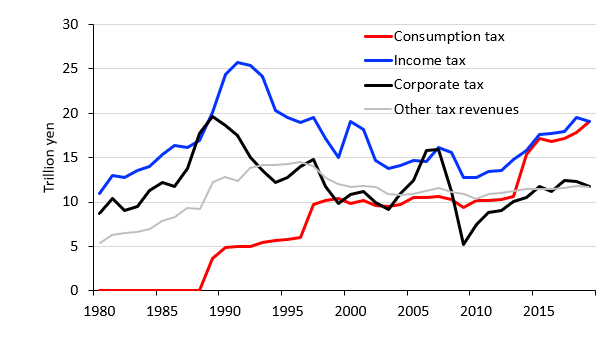

Figure 2: Social Security Expenditure and Local Allocation Tax as Share of Total Tax Revenues

Source: Ministry of Finance, Japan. Central Government.

At the same time Japan’s aging population ballooned the government contributions to the public pension and health insurance system, from 12 trillion yen (approx. 110 billion dollars) in 1990 to 36 trillion yen (approx. 327 billion dollars) in 2019. In addition, the so-called local allocation tax grants of around 16 trillion yen per year (approx. 145 billion dollars) to the economically exhausted Japanese periphery continued to constitute a heavy burden for the central government. In the wake of the global financial crisis, both together had increased far beyond the central governments’ tax revenues (Figure 2).

Persistent financing gaps could not be cured because of political and economic constraints. Cutting social benefits and local allocation tax grants were thought to be political harakiri because the over-aged population is concentrated in the Japanese periphery where the power base of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party lies. In the never-ending crisis, the government could not put greater tax burdens neither on companies nor on employees.

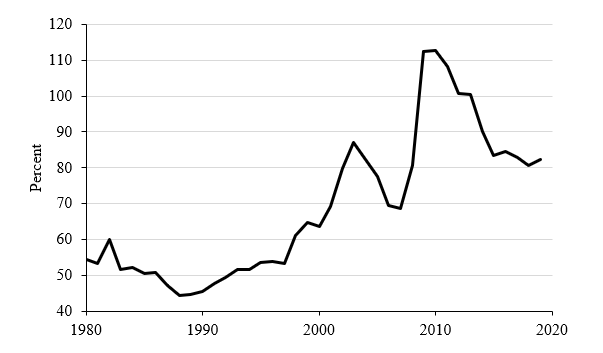

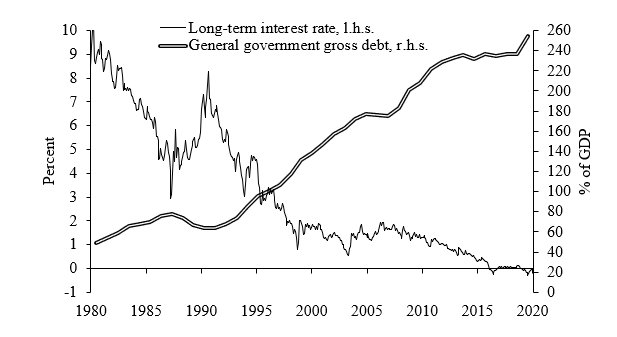

Therefore, the only way to raise revenues has been to lift the consumption tax, which was only 3 percent in 1990, when the crisis started. But even this approach was tricky because the Japanese voters dislike taxes and tax increases were seen as a threat to the economic recovery. Thus, the only politically feasible solution for the problem was raising debt, with Japanese general government debt hiking from 67 percent of GDP in 1990 to 240 percent in 2019 (Figure 3). The Bank of Japan prevented a public debt crisis by willingly buying huge amounts of governments bonds. This gradually depressed long-term interest rate to zero (Figure 3), thereby keeping public interest rate payments under control.

Figure 3: Japan: Long-term Interest Rate and General Government Gross Debt

Source: Ministry of Finance, Japan.

Although consumer price inflation has not picked up despite the huge monetary expansion, the great appetite of the Bank of Japan for government bonds has not been a free lunch. The costs of the long-term ultra-loose monetary policy emerged in form of paralyzed economic growth, as persistently low interest rates have zombified large parts of the Japanese economy, in particular in remote areas of Japan. As productivity growth has trended downwards, real wages have been declining since 1998 (Murai and Schnabl 2019). The gloomy economic prospects of large parts of the younger generation lead them to refrain from having more children. As many young people move from the periphery to the metropolitan areas to find jobs, the periphery ages more rapidly. Many small- and medium-sized firms go out of business, as customers are missing.

In this vicious circle, Abe’s consumption tax raises were merely an incomplete refill of tax revenues lost due to the self-imposed stagnation. At the same time, the huge excess of the social security expenditures was simply monetized by the Bank of Japan at the expense of overall welfare and the economic perspectives of Japan’s youth. The recent corona crisis is likely to reverse the recovery of tax revenues, which took place in the course of Abenomics. Therefore, the successor of Abe, Yoshihide Suga, will have to come up with new ideas if he aims to reanimate the Japanese economy.

Authors:

Taiki Murai is research assistant at the Institute for Economic Policy of Leipzig University.

Gunther Schnabl is a professor of international economics and economic policy in the department of economics at Leipzig University, Germany.