By Dr Frank Shostak

A common conception is that the central bank is a key factor in the determination of interest rates. On this way of thinking the key role of the central bank is to make sure that the so-called economy is placed on a trajectory of stable economic growth and stable inflation.

If for whatever reasons the economy appears to deviate from the specified trajectory then it is the responsibility of the central bank policy to ensure the economy remains on this path. This is attained so it is held, by means of influencing the short-term interest rate, in the US the federal funds rate.

The central bank influences the short-term interest rates by influencing monetary liquidity in the markets. Whilst buying assets by the US Fed raises the money supply, the selling of assets produces the opposite effect. Thus, by buying assets the Fed adds to the monetary liquidity thereby lowering rates. Whilst by selling assets, the exact opposite is taking place.

Popular thinking also suggest that long-term rates are the average of current and expected short-term interest rates. If today’s one year rate is 4% and the next year’s one-year rate is expected to be 5%, then the two-year rate today should be 4.5% ((4+5)/2=4.5%). Conversely, if today’s one year rate is 4% and the next year’s one-year rate expected to be 3%, then the two-year rate today should be 3.5% (4+3)/2=3.5%.

Time preference & interest rates

We suggest that it is individuals’ time preferences rather than the central bank that holds the key in the interest rate determination process. What is it all about?

An individual who has just enough resources to keep himself alive is unlikely to lend or invest his paltry means. The cost of lending, or investing, to him is likely to be very high – it might even cost him his life if he were to consider lending part of his means. Therefore, he is unlikely to lend, or invest even if offered a very high interest rate.

Once his wealth starts to expand, the cost of lending, or investing, starts to diminish. Allocating some of his wealth towards lending or investment is going to undermine to a lesser extent our individual’s life and wellbeing at present. On this Mises wrote,

That which is abandoned is called the price paid for the attainment of the end sought. The value of the price paid is called cost. Costs are equal to the value attached to the satisfaction which one must forego in order to attain the end aimed at.[1]

According to Carl Menger:

To the extent that the maintenance of our lives depends on the satisfaction of our needs, guaranteeing the satisfaction of earlier needs must necessarily precede attention to later ones. And even where not our lives but merely our continuing well-being (above all our health) is dependent on command of a quantity of goods, the attainment of well-being in a nearer period is, as a rule, a prerequisite of wellbeing in a later period……..All experience teaches that a present enjoyment or one in the near future usually appears more important to men than one of equal intensity at a more remote time in the future[2]

From this we can infer, all other things being equal, that anything that leads to the expansion in the real wealth of individuals should give rise to a decline in the interest rate i.e. the lowering of the premium of present goods versus future goods.

Conversely, factors that undermine real wealth expansion will lead to a higher interest rate. Note that increases in real wealth tend to lower individuals’ time preferences whereas decreases in real wealth tend to raise time preferences. The link however between changes in real wealth and changes in time preferences is not automatic. Every individual decides how to allocate his wealth in accordance with his priorities.

Demand for Money & Time Preference

The lowering of time preferences, i.e. the lowering of the premium of present goods versus future goods (due to real wealth expansion) is likely to become manifest in a greater eagerness to invest real wealth. With the expansion in real wealth, people are likely to increase their demand for various assets – financial and non-financial and lower their demand for money. In the process, this raises asset prices and lowers their yields, all other things being equal.

Observe that whilst the increase in the pool of real wealth is likely to be associated with a lowering in the interest rate, the opposite is likely to take place with a fall in the pool of real wealth. People are likely to be less eager to increase their demand for various assets thus raising their demand for money relative to the previous situation. Within all other things being equal, this will manifest in the lowering of the demand for assets thus lowering their prices and raising their yields.

What will happen to interest rates if the money supply increases?

An increase in the supply of money, all other things being equal, means that those individuals whose money stock has increased are now much wealthier. Hence, this will likely set in motion a greater willingness by these individuals to purchase various assets. This leads to the lowering of the demand for money by these individuals.

This in turn bids the prices of assets higher and lowers their yields. At the same time an increase in the money supply sets in motion an exchange of nothing for something which amounts to the diversion of real wealth from wealth generators to non-wealth generators. The consequent weakening in the real wealth formation process sets in motion a general rise in interest rates. This implies that an increase in the growth rate of money supply, all other things being equal sets in motion a temporary fall in interest rates. This decline in interest rates cannot be sustainable because of the damage to the process of real wealth generation.

A decline in the growth rate of money supply, all other things being equal, sets in motion a temporary increase in interest rates. However, over time, the fall in the money supply sets the foundation for a strengthening in the real wealth formation process, which sets in motion a general fall in interest rates.

We can thus see that the key for the determination of interest rates is individuals’ time preferences, which manifests through the interaction of supply and demand for money. Also, note, that in this way of thinking the central bank has nothing to do with the underlying interest rates determination. The policies of the central bank only distort where interest rates should be in accordance with time preferences, thereby making it much harder for businesses to ascertain what is really going on.

Stagflation and interest rates

In the situation when economic activity is declining whilst price inflation is strengthening how is this likely to affect interest rates? What we have here is stagflation i.e. a strengthening in price inflation and a decline in economic activity. We hold that the key factor behind stagflation is the previous strong increases in money supply, which undermines the pool of real wealth. Strong increases in money supply result in an exchange of nothing for something, which weakens the process of real wealth formation. As a result a weakening in the pool of real wealth in turn weakens real economic growth.

At the same time, increases in the money supply weakens the purchasing power of money. Hence, we have here a weakening in economic activity and a general increase in price inflation. A weakening in the process of wealth generation due to the strengthening in the money supply growth rate increases individuals time preferences i.e. the underlying real interest rates are going up.

In response to the emerging economic slump, the central bank enters the scene to counter the slump by lifting the money supply growth rate further. This pushes asset prices higher thereby lowering their yields. After a time lag though, this increase in the money supply and resultant increase in price inflation is likely to prompt the Fed to reverse and tighten its interest rate stance. This means that relative to the previous situation the Fed is likely to reduce its buying of assets. Consequently, upward pressure on interest rates is likely to emerge. However, this upward pressure on yields should only be temporary since a tighter monetary stance is actually good news for the formation of real wealth. This means that after a time lag this is likely to lower individual time preferences and work towards the lowering real interest rates.

The 1970’s is a great example of stagflation. After closing at 2.7% in June 1972 the yearly growth rate of the US CPI jumped to 12.3% by December 1974. The yearly growth rate of industrial production, which closed at 11.6% by December 1972, plunged to minus 12.4% by May 1975.

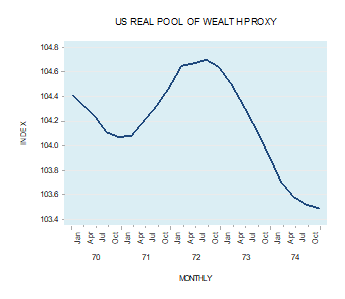

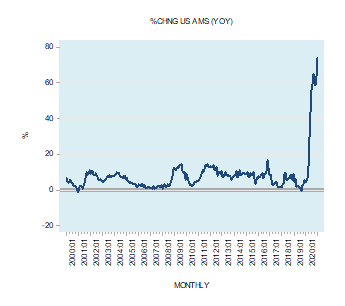

Note that a strong increase in the growth rate of money AMS from 2.7% in May 1970 to 9.6% in February 1973 was an important cause behind the strong acceleration in price inflation during June 1972 to December 1974. At the same time, this strong increase in the momentum of AMS had likely undermined the pool of real wealth (see chart). This likely real wealth erosion coupled with a decline in the yearly growth rate of AMS from 9.6% in February 1973 to 4.1% in December 1974 weakened the momentum of industrial production.

Are we heading for stagflation?

Given that the yearly growth rate of US AMS stood at 74% at the end of December 2020 (see chart) this raises the likelihood of a strong increase in price inflation ahead. We are concerned that as a result of past reckless fiscal and monetary policies the pool of real wealth could be declining. If this is the case then it is possible that the monetary pumping will not be effective in terms of getting the economy out of the slump. This we suggest raises the likelihood of stagflation ahead.

Observe though that the Fed increased the fed funds rate target from 5.5% in June 1972 to 11% in June 1974. Afterwards the target was lowered to 8% by December 1974. Note that the Fed was pursuing a tighter interest rate stance until June 1974 whilst the momentum of industrial production was declining. Contrary to that period, we are currently do not assign a high probability that the Fed is going to tighten its interest rate stance soon. The major reason being that whilst we do anticipate a likely increase in price inflation sometime in the future, a major consideration of the Fed is likely to be that the US economy still remains vulnerable to the paralyzing effects of the COVID 19 such as lockdowns. (It is still not clear whether various vaccines are going to be effective in countering the COVID 19).

[1] Ludwig von Mises, “Human Action” Contemporary Books, 3rd revised edition p 97.

[2] Carl Menger Principles of Economics, New York University Press p 153-154.