Initiated by monetarists, the debate between an outlook for inflation versus recession intensifies. We appear to be moving on from the stagflation story into outright fears of the consequences of monetary tightening and of interest rate overkill.

In common with statisticians in other jurisdictions, Britain’s Office for Budget Responsibility is still effectively saying that inflation of prices is transient, though the prospect of a return towards the 2% target has been deferred until 2024. Chancellor Sunak blithely accepts these figures to justify a one-off hit on oil producers, when, surely, with his financial expertise he must know the situation is likely to be very different from the OBR’s forecasts.

This article clarifies why an entirely different outcome is virtually certain. To explain why, the reasonings of monetarists and neo-Keynesians are discussed and the errors in their understanding of the causes of inflation is exposed.

Finally, we can see in plainer sight the evolving risk leading towards a systemic fiat currency crisis encompassing banks, central banks, and fiat currencies themselves. It involves understanding that inflation is not rising prices but a diminishing purchasing power for currency and bank deposits, and that the changes in the quantity of currency and credit discussed by monetarists are not the most important issue.

In a world awash with currency and bank deposits the real concern is the increasing desire of economic actors to reduce these balances in favour of an increase in their ownership of physical assets and goods. As the crisis unfolds, we can expect increasing numbers of the public to attempt to reduce their cash and bank deposits with catastrophic consequences for their currencies’ purchasing power.

That being so, we appear to be on a fast track towards a final crack-up boom whereby the public attempts to reduce their holdings of currency and bank deposits, evidenced by selected non-financial asset and basic consumer items prices beginning to rise rapidly.

IntroductionIn the mainstream investment media, the narrative for the economic outlook is evolving. From inflation, by which is commonly meant rising prices, the MSIM say we now face the prospect of recession. While dramatic, current inflation rates are seen to be a temporary phenomenon driven by factors such as Russian sanctions, Chinese covid lockdowns, component shortages and staffing problems. Therefore, it is said, inflation remains transient — it’s just that it will take a little longer than originally thought by Jay Powell to return to the 2% target.

We were reminded of this in Britain last week when Chancellor Sunak delivered his “temporary targeted energy profits levy”, which by any other name was an emergency budget. Note the word “temporary”. This was justified by the figures from the supposedly independent Office for Budget Responsibility. The OBR still forecasts a return to 2% price inflation but deferred until early 2024 after a temporary peak of 9%. Therefore, the OBR deems it is still transient. Incidentally, the OBR’s forecasting record has been deemed by independent observers as “really terrible”.[i]

Absolved himself of any responsibility for the OBR’s inflation estimates, Sunak is spending £15bn on subsidies for households’ fuel costs, claiming to recover it from oil producers on the argument that they are enjoying an unexpected windfall, courtesy of Vladimir Putin, to be used to finance a one-off temporary situation.

That being the case, don’t hold your breath waiting for Shell and BP to submit a bill to Sunak for having to write off their extensive Russian investments and distribution businesses because of UK government sanctions against Russia. But we digress from our topic, which is about the future course of prices, more specifically the unmeasurable general price level in the context of economic prospects. And what if the OBR’s figures, which are like those of all other statist statisticians in other jurisdictions, turn out to be hideously wrong?

There is no doubt that they and the MSIM are clutching at a straw labelled “hope”. Hope that a recession will lead to lower consumer demand taking the heat out of higher prices. Hope that Putin’s war will end rapidly in his defeat. Hope that Western sanctions will collapse the Russian economy. Hope that supply chains will be rapidly restored to normal. But even if all these expectations turn out to be true, old-school economic analysis unbiased by statist interests suggests that interest rates will still have to go significantly higher, bankrupting businesses, governments, and even central banks overloaded with their QE-derived portfolios.

The establishment, the mainstream media and government agencies are deluding themselves over prospects for prices. Modern macroeconomics in the form of both monetarism and Keynesianism is not equipped to understand the economic relationships that determine the future purchasing power of fiat currencies. Taking our cue from the stagflationary seventies, when Keynesianism was discredited, and Milton Friedman of the Chicago monetary school came to prominence, we must critically examine both creeds. In this article we look at what the monetarists are saying, then the neo-Keynesian mainstream approach, and finally the true position and the outcome it is likely to lead to.

Since monetarists are now warning that a slowdown in credit creation is tilting dangers away from inflation towards recession, we shall consider the errors in the monetarist approach first.

Monetary theory has not yet adapted itself for pure fiatMonetarist economists are now telling us that the growth of money supply is slowing, pointing to a recession. But that is only true if all the hoped-for changes in prices comes from the side of goods and services and not that of the currency. No modern monetarist appears to take that into account in his or her analysis of price prospects, bundling up this crucial issue in velocity of circulation. This is why they often preface their analysis by assuming there is no change in velocity of circulation.

While they have turned their backs on sound money, which can only be metallic gold or silver and their credible substitutes, their analysis of the relationship between currency and prices has not been adequately revised to account for changes in the purchasing power of pure fiat currencies. It is vitally important to understand why it matters.

A proper gold coin exchange standard turns a currency into a gold substitute, which the public is almost always content to hold through cycles of bank credit. While there are always factors that alter the purchasing power of gold and its relationship with its credible substitutes, the purchasing power of a properly backed currency and associated media in the form of notes and bank deposits varies relatively little compared with our experience today, particularly if free markets permit arbitrage between different currencies acting as alternative gold substitutes.

This is demonstrated in Figure 1 below of the oil price measured firstly in gold-grammes and currencies under the Bretton Woods agreement until 1971, and then gold-grammes and pure fiat currencies subsequently. The price stability, while economic actors accepted that the dollar was tied to gold and therefore a credible substitute along with the currencies fixed against it, was evident before the Bretton Woods agreement was suspended. Yet the quantity of currency and deposits in dollars and sterling expanded significantly during this period, more so for sterling which suffered a devaluation against the dollar in 1967. The figures for the euro before its creation in 2000 are for the Deutsche mark, which by following sounder money policies while it existed explains why the oil price in euros is recorded as not having risen as much as in sterling and the dollar.

The message from oil’s price history is that volatility is in fiat currencies and not oil. In gold-grammes there has been remarkably little price variation. Therefore, the pricing relationship between a sound currency backed by gold differs substantially from the fiat world we live with today, and there has been very little change in monetarist theory to reflect this fact beyond mere technicalities.

The lesson learned is that under a gold standard, an expansion of the currency and bank deposits is tolerated to a greater extent than under a pure fiat regime. But an expansion of the media of exchange can only be tolerated within limits, which is why first the London gold pool failed in the late 1960s and then the Bretton Woods system was abandoned in 1971.

Under a gold standard, an expansion of the quantity of bank credit will be reflected in a currency’s purchasing power as the new media is absorbed into general circulation. But if note-issuing banks stand by their promise to offer coin conversion to allcomers that will be the extent of it and economic actors know it.

This is the basis behind classical monetarism, which relates with Cantillon’s insight about how new money enters circulation, driving up prices in its wake. From John Stuart Mill to Irving Fisher, it has been mathematically expressed and refined into the equation of exchange. In his earlier writings, even Keynes understood monetarist theory, giving an adequate description of it in his Tract on Monetary Reform, written in 1923 when Germany’s papiermark was collapsing. But even under the gold standard, the monetarist school failed to incorporate the reality of the human factor in their equation of exchange, which has since become a glaring omission with respect to fiat currency regimes.

Buyers and sellers of goods and services do not concern themselves with the general price level and velocity of circulation; they are only concerned with their immediate and foreseeable needs. And they are certainly unaware of changes in the quantity of currency and credit and the total value of past transactions in the economy. Consumers and businesses pay no attention to these elements of the fundamental monetarist equation.

In essence, this is the disconnection between monetarism and catallactic reality. Instead, the equation of exchange is made to always balance by the spurious concept of velocity of circulation, a mental image of money engendering its own utility rather than being simply a medium of exchange between buyers and sellers of goods and services. And mathematicians who otherwise insist on the discipline of balance in their equations are seemingly prepared in the field of monetary analysis to introduce a variable whose function is only to ensure the equation always balances when without it, it does not.

Besides monetarism failing to account for the human actions of consumers and businesses, over time there have been substantial shifts in how money is used for purposes not included in consumer transactions — the bedrock of consumer price indices and of gross domestic product. The financialisation of the US and other major economies together with the manufacture of consumer and intermediate goods being delegated to emerging economies have radically changed the profiles of the US and the other G7 economies. To assume, as the monetarists do, that the growth of money supply can be applied pro rata to consumer activity is a further error because much of the money supply does not relate to prices of goods and services.

Furthermore, when cash and bank deposits are retained by consumers and businesses, for them they represent the true function of money, which is to act as liquidity for future purchases. They are not concerned with past transactions. Therefore, the ratio of cash and instant liquidity to anticipated consumption is what really matters in determining purchasing power and cannot be captured in the equation of exchange.

Monetarists have stuck with an equation of exchange whose faults did not matter materially under proper gold standards. Besides ignoring the human element in the marketplace, their error is now to persist with the equation of exchange in a radically different fiat environment.

The role of cash and credit reservesIn their ignorance of the importance of the ratio between cash and credit relative to prospective purchases of goods and services, all macroeconomists commit a major blunder. It allows them to argue inaccurately that an economic slowdown triggered by a reduction in the growth of currency and credit will automatically lead to a fall in the rate of increase in the general price level. Having warned central banks earlier of the inflation problem with a degree of success, this is what now lies behind monetarists’ forecasts of a sharp slowdown in the rate of price increases.

A more realistic approach is to try to understand the factors likely to affect the preferences of individuals within a market society. For individuals to be entirely static in their preferences is obviously untrue and they will respond as a cohort to the changing economic environment. It is individuals who set the purchasing power of money in the context of their need for a medium of exchange — no one else does. As Ludwig von Mises put it in his Critique of Interventionism:

“Because everybody wishes to have a certain amount of cash, sometimes more sometimes less, there is a demand for money. Money is never simply in the economic system, in the national economy, it is never simply circulating. All the money available is always in the cash holdings of somebody. Every piece of money may one day — sometimes oftener, sometimes more seldom — pass from one man’s cash holding to another man’s ownership. At every moment it is owned by somebody and is a part of his cash holdings. The decisions of individuals regarding the magnitude of their cash holdings constitute the ultimate factor in the formation of purchasing power.”[i]

For clarification, we should add to this quotation from Mises that cash and deposits include those held by businesses and investors, an important factor in this age of financialisation. Aside from fluctuations in bank credit, units of currency are never destroyed. It is the marginal demand for cash that sets it value, its purchasing power. It therefore follows that a relatively minor shift in the average desire to hold cash and bank deposits will have a disproportionate effect on the currency’s purchasing power.

Central bankers’ instincts work to maintain levels of bank credit, replacing it with central bank currency when necessary. Any sign of a contraction of bank credit, which would tend to support the currency’s purchasing power, is met with an interest rate reduction and/or increases in the note issue and in addition today increases of bank deposits on the central bank’s balance sheet through QE. The expansion of global central bank balance sheets in this way has been mostly continuous following the Lehman crisis in 2008 until March, since when they began to contract slightly in aggregate — hence the monetarists’ warnings of an impending slowdown in the rate of price inflation.

But the slowdown in money supply growth is small beer compared with the total problem. The quantity of dollar notes and bank deposits has tripled since the Lehman crisis and GDP has risen by only two-thirds. GDP does not account for all economic transactions — trading in financial assets is excluded from GDP along with that of most used goods. Even allowing for these factors, the quantity of currency liquidity for economic actors must have increased to unaccustomed levels. This is further confirmed by the Fed’s reverse repo balances, which absorb excess liquidity of currency and credit currently standing at about $2 trillion, which is 9% of M2 broad money supply.

In all Western jurisdictions, consuming populations are collectively seeing their cash and bank deposits buy less today than in the past. Furthermore, with prices rising at the fastest rate seen in decades, they see little or no interest compensation for retaining balances of currencies losing purchasing power. In these circumstances and given the immediate outlook for prices they are more likely to seek to decrease their cash and credit balances in favour of acquiring goods and services, even when they are not for immediate use.

The conventional solution to this problem is the one deployed by Paul Volcker in 1980, which is to raise interest rates sufficiently to counter the desire of economic actors to reduce their spending liquidity. The snag is that an increase in the Fed funds rate today sufficient to restore faith in holding bank deposits would have to be to a level which would generate widespread bankruptcies, undermine government finances, and even threaten the solvency of central banks, thereby bringing forward an economic and banking crisis as a deliberate act of policy.

The egregious errors of the neo-Keynesian cohortUnlike the monetarists, most neo-Keynesians have discarded entirely the link between the quantity of currency and credit and their purchasing power. Even today, it is neo-Keynesians who dominate monetary and economic policy-making, though perhaps monetarism will experience a policy revival. But for now, with respect to inflation money is rarely mentioned in central bank monetary committee reports.

The errors in what has evolved from macroeconomic pseudo-science into beliefs based on a quicksand of assumptions are now so numerous that any hope that those in control know what they are doing must be rejected. The initial error was Keynes’s dismissal of Say’s law in his General Theory by literary legerdemain to invent macroeconomics, which somehow hovers over economic reality without being governed by the same factors. From it springs the belief that the state knows best with respect to economic affairs and that all the faults lie with markets.

Every time belief in the state’s supremacy is threatened, the Keynesians have sought to supress the evidence offered by markets. Failure at a national level has been dealt with by extending policies internationally so that all the major central banks now work together in group-thinking unison to control markets. We have global monetary coordination at the Bank for International Settlements. And at the World Economic Forum which is trying to muscle in on the act we now see neo-Marxism emerge with the desire for all property and personal behaviour to be ceded to the state. As they say, “own nothing and you will be happy”.

The consequence is that when neo-Keynesianism finally fails it will be a global crisis and there will be no escape from the consequences in one’s own jurisdiction.

The current ideological position is that prices are formed by the interaction of supply and demand and little else. They make the same error as the monetarists in assuming that in any transaction the currency is constant and all the change in prices comes from the goods side: money is wholly objective, and all the price subjectivity is entirely in the goods. This was indeed true when money was sound and is still assumed to be the case for fiat currencies by all individuals at the point of transaction. But it ignores the question over a currency’s future purchasing power, which is what the science of economics should be about.

The error leads to a black-and-white assumption that an economy is either growing or it is in recession — the definitions of which, like almost all things Keynesian, are somewhat fluid and indistinct. Adherents are guided religiously by imperfect statistics which cannot capture human action and whose construction is evolved to support the monetary and economic policies of the day. It is a case of Humpty Dumpty saying, “It means what I chose it to mean —neither more nor less” Lewis Caroll fans will know that Alice responded, “The question is whether you can make words mean so many different things”. To which Humpty replied,” The question is which is to be master —that’s all.”

So long as the neo-Keynesians are Masters of Policy their imprecisions of definition will guarantee and magnify an eventual economic failure.

The final policy crisis is approachingWhether a macroeconomist is a monetarist or neo-Keynesian, the reliance on statistics, mathematics, and belief in the supremacy of the state in economic and monetary affairs ill-equips them for dealing with an impending systemic and currency crisis. The monetarists argue that the slowdown in monetary growth means that the danger is now of a recession, not inflation. The neo-Keynesians believe that any threat to economic growth from the failures of free markets requires further stimulation.

The measure everyone uses is growth in gross domestic product, which only reflects the quantity of currency and credit applied to transactions included in the statistic. It tells us nothing about why currency and credit is used. Monetary growth is not economic progress, which is what increases a nation’s wealth. Instead, self-serving statistics cover up the transfer of wealth from the producers in an economy to the unproductive state and its interests through excessive taxation and currency debasement, leaving the entire nation, including the state itself eventually, worse off. For this reason, attempts to increase economic growth merely worsen the situation, beyond the immediate apparent benefits.

There will come a point when the public wakes up to the illusion of monetary debasement. Until recently, there has been little evidence of this awareness, which is why the monetarists have been broadly correct about the price effects of the rapid expansion of currency and credit in recent years. But as discussed above, the expansion of currency and bank deposits has been substantially greater than the increase in GDP, which despite its direction into financial speculation and other activities outside GDP has led to an accumulation of over $2 trillion of excess liquidity no one wants in US dollar reverse repos at the Fed.

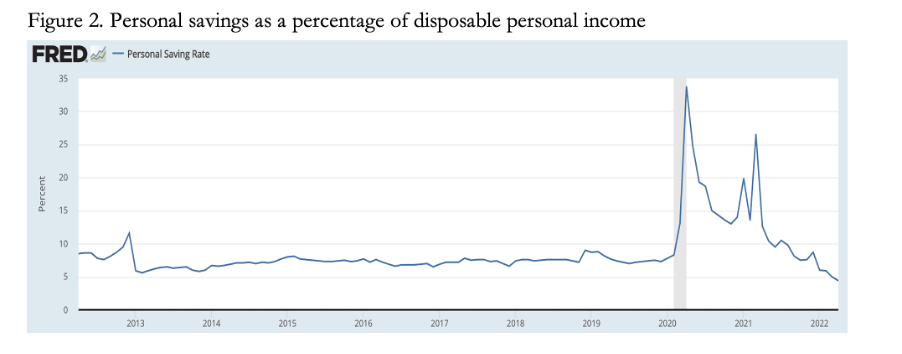

The growth in the level of personal liquidity and credit available explains why the increase in the general price level for goods and services has lagged the growth of currency and deposits, because at the margin since the Lehman crisis the public, including businesses and financial entities, has been accumulating additional liquidity instead of buying goods. This accelerated during covid lockdowns to be subsequently released in a wave of excess demand, fuelling a sharp rise in the general level of prices, not anticipated by the monetary authorities who immediately dismissed the rise as transient. The build-up of liquidity and its subsequent release into purchases of goods is reflected in the savings rate for the US shown in Figure 2 below.

The personal saving rate does not isolate from the total the accumulating level of spending liquidity as opposed to that allocated for investment. The underlying level of personal liquidity will have accumulated over time as a part of total personal savings in line with the growth of currency and bank deposits since the Lehman crisis. The restrictions on spending behaviour during lockdowns in 2020 and 2021 exacerbated the situation, forcing a degree of liquidity reduction which drove the general level of prices significantly higher.

Profits and losses resulting from dealing in financial assets and cryptocurrencies are not included in the personal savings rate statistics either. This matters to the extent that bank credit is used to leverage investment. Nor is the accumulation of cash in corporations and financial entities, which are a significant factor. But whatever the level of it, there can be little doubt that the levels of liquidity held by economic actors are unaccustomedly high.

The accumulation of reverse repos representing unwanted liquidity informs us that the public, including businesses, are so sated with excess liquidity that they may already be trying to reduce it, particularly if they expect further increases in prices. In that event they will almost certainly bring forward future purchases to alter the relationship between personal liquidity and goods.

It is a situation in America which is edging towards a crack-up boom. A crack-up boom occurs when the public as a cohort attempts to reduce the overall level of its currency and deposits in favour of goods towards a final point of rejecting the currency entirely. So far, economic history has recorded only one version, which is when after a period of accelerating debasement of a fiat currency the public finally wakes up to the certainty that a currency is becoming worthless and all hope that it might somehow survive as a medium of exchange must be abandoned. To this, perhaps we can add another: the consequences of a collapse of the world’s major monetary institutions in unison.

How excess liquidity is likely to play out

We have established beyond reasonable doubt that the US economy is awash with personal liquidity. And if one man disposes of his liquidity to another in a transaction the currency and bank deposit still exists. But aggregate personal liquidity can be reduced by the contraction of bank credit. As interest rates rise, thereby exposing malinvestments, the banks will be quick to protect themselves by withdrawing credit. As originally described by Irving Fisher, a contraction of bank credit risks triggering a self-feeding liquidation of loan collateral.

Initially, we can expect central banks to counter this contraction by redoubling efforts to suppress bond yields, reinstitute more aggressive QE, and standing ready to bail out banks. These are all measures which are in the central banker’s instruction manual. But the conditions leading to a crack-up boom appear to be already developing despite the increasing likelihood of contracting bank credit. The deteriorating outlook for bank credit and the impact on highly leveraged banks, particularly in Japan and the Eurozone, is likely to accelerate the flight out of bank deposits to — where?

Regulators have deliberately reduced access to currency cash so a bank depositor can only dispose of larger sums by transferring them to someone else. Before an initial rise in interest rates began to undermine financial asset values, a transfer of a bank deposit to a seller of a financial asset was a viable alternative. That is now an increasingly unattractive option due to the changed interest rate environment. Consequently, the principal alternative to holding bank deposits is to acquire physical assets and consumer items for future use.

But even that assumes an overall stability in the public’s collective willingness to hold bank deposits, which without a significant rise in interest rates is unlikely to be the case. The reluctance of a potential seller to increase his bank deposits is already being reflected in prices for big ticket items, such as motor cars, residential property, fine and not-so-fine art, and an increasing selection of second-hand goods.

This is not an environment that will respond positively to yet more currency debasement and interest rate suppression as the monetary authorities struggle to maintain control over markets. The global financial bubble is already beginning to implode, and the central banks which have accumulated large portfolios through quantitative easing are descending into negative equity. Only this week, the US Fed announced that it has unrealised portfolio losses of $330bn against equity of only $50bn. The Fed can cover this discrepancy if it is permitted by the US Treasury to revalue its gold note to current market prices – but further rises in bond yields will rapidly wipe even that out. Other central banks do not have this leeway, and in the cases of the ECB and the Bank of Japan, they are invested in considerably longer average bond maturities, which means that as interest rates rise their unrealised losses will be magnified.

So, the major central banks are insolvent or close to it and will themselves have to be recapitalised. At the same time, they will be required to backstop a rapidly deteriorating economic situation. And being run by executives whose economic advisers do not understand both economics nor money itself, it all amounts to a recipe for a final cock-up crack-up boom as economic actors seek to protect themselves.

As the situation unfolds and economic actors become aware of the true inadequacies of bureaucratic group-thinking central bankers, the descent into the ultimate collapse of fiat currencies could be swift. It is now the only way in which all that excess faux liquidity can be expunged.

[i] Originally published in 1929 in German. The quote is taken from the latest English revised translation by Hans Sennholz (Irvington-on-Hudson, NY: Foundation for Economic Eduction, 1996.

[i]https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2021/10/28/the-office-for-budget-responsibility-is-a-really-terrible-economic-forecaster/