A recent Bank for International Settlements paper warning of unappreciated risks in foreign exchange markets echoes my earlier warning in an article for Goldmoney published over a month ago describing derivative risks in FX markets.[i]

In this article I also show evidence that banks in both the US and Eurozone are reducing the deposit side of their balance sheets by turning away big deposits which are ending up in central bank reverse repos, parking unwanted liquidity out of public circulation. The great unwind is well under way.

Credit contraction is not only driving a bear market in financial assets, but the exposure to malinvestments by rising interest rates is having negative consequences for the non-financial economy as well. Private equity, which has thrived on cheap finance used to leverage targeted businesses, is showing signs of unwinding with two major Blackrock funds suspending redemptions.

As we approach the season for year-end window dressing, we must hope that the volatility in thin markets that often accompanies it does not destabilise global financial markets.

Inflation and stagnation

Make no mistake: interest rates have bottomed at the zero bound and can go no lower. The forty-year trend of declining interest rates has ended, with an initial rally, which six weeks ago had halved the value of the 30-year US Treasury bond. The suddenness of this change probably needed a pause, and that is what we have today. Since October, there has been a spectacular recovery in bond prices with this UST bond yield dropping ¾% to 3.5%.

Fears of price inflation have been replaced in large measure by fear of recession. Having dismissed monetarism, bizarrely for a Keynesian led establishment analysts and commentators are now frequently citing the slowing of monetary growth as evidence of a looming recession. Perhaps this means that the failure of their economic models has them grasping at straws, rather than being evidence of a conversion to monetarism. But what is definitely not in the Keynesians’ playbook is a combination of inflation and recession, commonly attributed to an unexplained phenomenon of stagflation.

A moment’s thought explains the coincidence of the two. Inflation of total credit (both by central banks and commercial banks) transfers wealth from private sector actors to the State, its licenced banks, and their favoured borrowers. It acts as a suffocating hidden tax on economic progress, impoverishing ordinary people, and through their desire to protect themselves from credit debasement, driving otherwise productive capital resources into “safe havens”, such as physical property and financial speculation. There comes a point where the stimulative effects of credit expansion, which is a device to trick markets into thinking that things are better than they really are, becomes outright destructive.

If it was otherwise, currency debasement would work even history plainly shows it to be a destructive, failed policy. And in extremis, nations as diverse as 1920s Germany and today’s Zimbabwe would have been roaring successes from an economic point of view with their nominal GDP soaring off the scale. By way of contrast, post-WW2 Germany and Japan adopted monetary policies which led to strong currencies, yet they still outperformed the socks off the inflationary Anglo-Saxons.

Both the empirical evidence and logic are ignored by policy makers and an investment establishment dedicated to believing otherwise for the sake of their macroeconomic dogmas. Like drowning men, they grasp evidence that the initial surge in prices, attributed conveniently to covid, supply chain disruption, and sanctions against Russia is slowing. And that increases in the CPI will subside. Undoubtedly, they will. But this is a statistical aberration because high numbers will drop out of the back end of a rolling statistic. It allows perennial bulls to call an end in sight to interest rate rises, and with a recession in prospect for that trend to be reversed. QT will be replaced again with QE — that is certainly believable.

These expectations for the inflation outlook and therefore interest rates are too glib. As well as compensation for temporary loss of possession of credit and for counterparty risk, interest rates are bound to reflect a creditor’s view of changes in a currency’s purchasing power. Much of the time, a central bank can impose an interest rate policy on markets, as the evidence shows. But there comes a point where, recognising the debasement of a currency the market forces a central bank to concede higher rates. The market in question is usually the foreign exchanges.

This is why with the path clearing towards a new softening of interest rate policy, the dollar has weakened dramatically against the other principal currencies along with the fall in US Treasury yields for longer maturities.

As to the course of future interest rates, we must make an assessment beyond the visible prospects for a recession. We must anticipate central bank policies and their consequences: will they abandon inflationism and seek to protect their currency, or will they prioritise protecting the economy from recession, from the illusion of financial wealth created by interest rate suppression, and to protect deteriorating government finances?

When fiat currencies can be readily expanded to deal with all these escalating problems, whatever the stated intention of monetary policy inflationism proves irresistible. And all the more so, when the alternative of credit restriction is bound to crash the economy, financial markets, and government finances.

Commercial bankers are not stupid, and with over-leveraged balance sheets are certain to try to protect themselves from mounting bad debts in a recessionary environment. The extent to which they do so throws an additional burden of credit creation onto central banks. But all the evidence shows that central bank monetary policy has a far greater impact on a currency’s valuation on the foreign exchanges than equivalent variations in commercial bank credit. Therefore, the effect of central bank credit replacing commercial bank credit is to rapidly undermine a currency’s value.

All major governments are caught in debt traps, which are being sprung by higher interest rates. And when central banks band together to protection their failing economies, as they seem certain to do, exchange rates may appear to be stable. But the loss of purchasing power then begins to be reflected for all currencies in gold, commodity prices, and production costs, despite consumption declining.

Therefore, there can only be one conclusion about the future course of interest rates. The trend has turned and after an initial rise have paused. This softening of the interest rate outlook will turn out to be temporary, to be followed by a continuing trend of yet higher rates, reflecting more aggressive currency debasement, awkwardly coinciding with a deepening slump in economic activity. This must be our basic assumption.

Financial sector woes

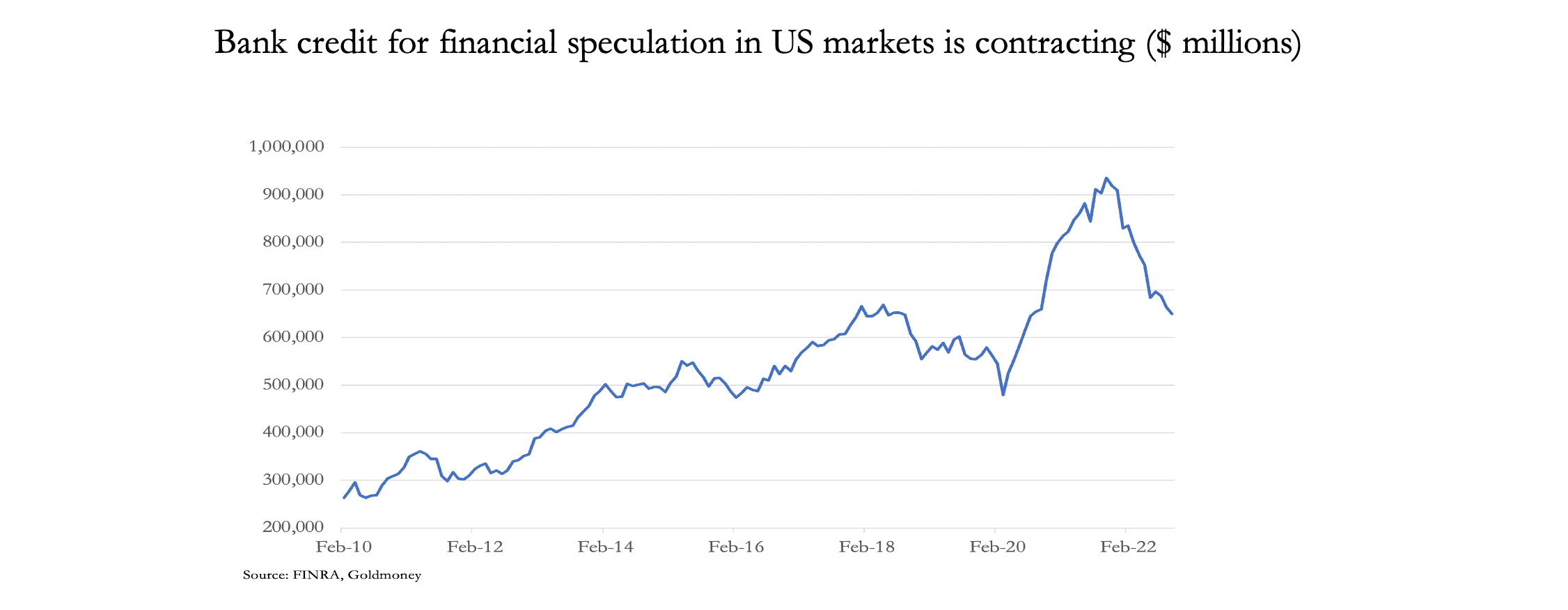

The most obvious consequence of a new trend of rising rates is falling values for financial assets. All financial markets take their cue from bond markets. From the commercial bankers’ point of view, they find that collateral values against customer loans start to decline, leading to pressure for additional collateral. Obviously, this leads to the decline in total loans supporting positions in stocks and bonds, as the next chart shows which is of outstanding margin credit in US financial markets.

The evidence from FINRA is that banks are reducing their loan exposure to stock and bond markets. It is likely that diminishing collateral margins are causing investment positions to be liquidated, with lenders reluctant to blindly accept additional margin liquidity. We can assume this is so, because of the need for banks to reduce their balance sheet leverage. The recent rally in bond and equity prices might provide some relief (the chart above is up to October), but it is unlikely to be permenant if, as seems likely, central banks stop quantitative tightening and begin easing again.

The reason an easing of monetary policy is unlikely to sustain a durable recovery in financial asset values is because by choosing to reflate the economy and markets, the currency is sacrificed. A decline in a currency’s purchasing power is initially foreseen by dealers on the foreign exchanges. Furthermore, any confusion over this relationship between monetary policies and their consequences for a fiat currency has been settled by the link between covid related credit expansion engineered by the central banks and subsequent price inflation. Markets are unlikely to be fooled so easily by the expansion of central bank credit in future.

While stock and bond commentary are relatively easy topics for commentators, the source of unpleasant surprises is hidden from their view. In a previous article,[ii] I described such a situation in derivative markets, pointing out that the notional values of foreign exchange crosses, forwards, and swaps totalled a notional $104 trillion — the BIS’s figure for mid-2021. Foreign exchange contracts are the second largest segment of the $600 trillion OTC total. According to the BIS’s triannual survey, only 84% of foreign exchange contracts are captured in the semi-annual statistics, so a truer figure is $124 trillion.

By maturity, they split 80% up to a year, 15% one to five years, and the rest over five years. Because all foreign exchange contracts in the BIS’s statistics represent only one side of foreign exchange contracts, the whole amount of $124 trillion are definitely credit, the majority of which, only excluding options, is duplicated by matching credit obligations for the other counterparties. Therefore, total foreign exchange derivative credit in trillions is at least double notional amounts outstanding, less one side of notional options. This amounts to $236 trillion.

According to the BIS, the gross market value of this credit is $2.548 trillion. The BIS defines gross market value as “the sum of the absolute values of all outstanding derivatives contracts with either positive or negative replacement values evaluated at market prices prevailing on the settlement date”. In other words, the extent to which the banking system, non-banks and non-financial counterparties are counterparties to these OTC derivatives, their balance sheets reflect this net mark-to-market figure, and not actual credit obligations, which are almost a hundred times greater.

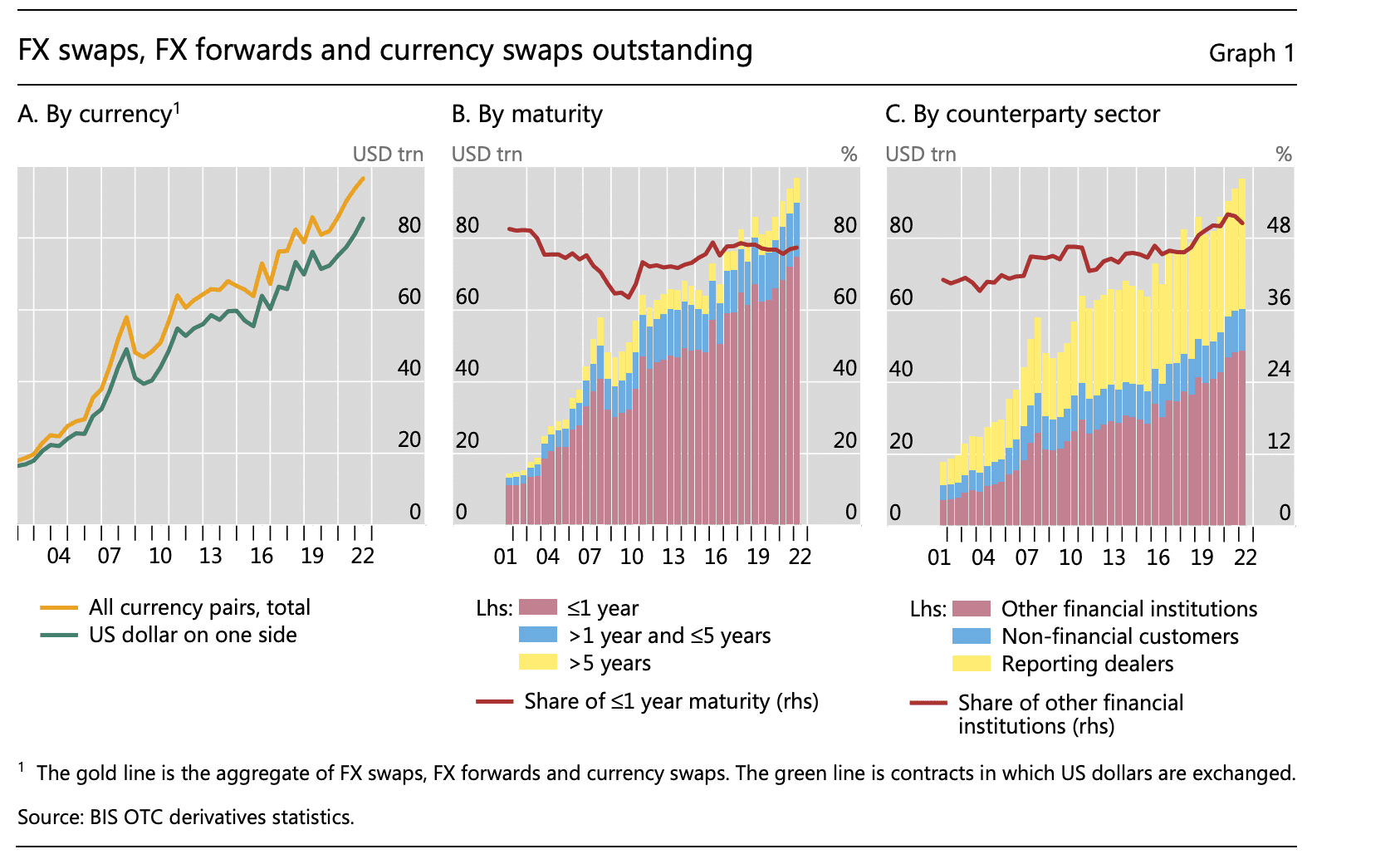

Since my article, Claudio Borio et al in a research paper for the Bank for International Settlements have made the same point adding some additional colour. The graphs below are taken from Borio’s paper, showing only one side of the notional values of FX positions updated to end-June this year.[iii]

It should be noted that this OTC market is dominated by US dollar positions, totalling over $80 trillion (Chart A), that there is a preponderance of short-term, liquidity vulnerable maturities (Chart B), and that non-bank financial entities are the largest category by far (shadow banks — Chart C). And the paper also points out that the Fed is responsible for ensuring that there is sufficient dollar liquidity to support these enormous off-balance sheet obligations.

The two instances of failure — the financial crisis of 2008/09 and of March 2020 (the repo crisis in September 2019 was unrelated) had the Fed flying blind, not knowing the extent of these obligations and where they were located. In effect, along with all its other obligations the Fed must ensure the integrity of the entire global FX market, which the BIS paper estimates include more than $35 trillion in the hands of foreign non-banks.

What could go wrong? Clearly this is a situation made more dangerous in a long-term trend for rising interest rates. Just as this and other OTC markets have grown on the back of forty years of declining interest rates, they will contract in size as the new trend progresses. In a secular financial sector slump, institutions which have come to rely on derivatives for risk protection or for trading profits are bound to be exposed to settlement failures, triggered when one or more counterparties fail to deliver on their obligations. The preponderance of non-bank, foreign, and short-term liquidity-vulnerable FX positions is a combination which is at high risk of leading to an unexpected event.

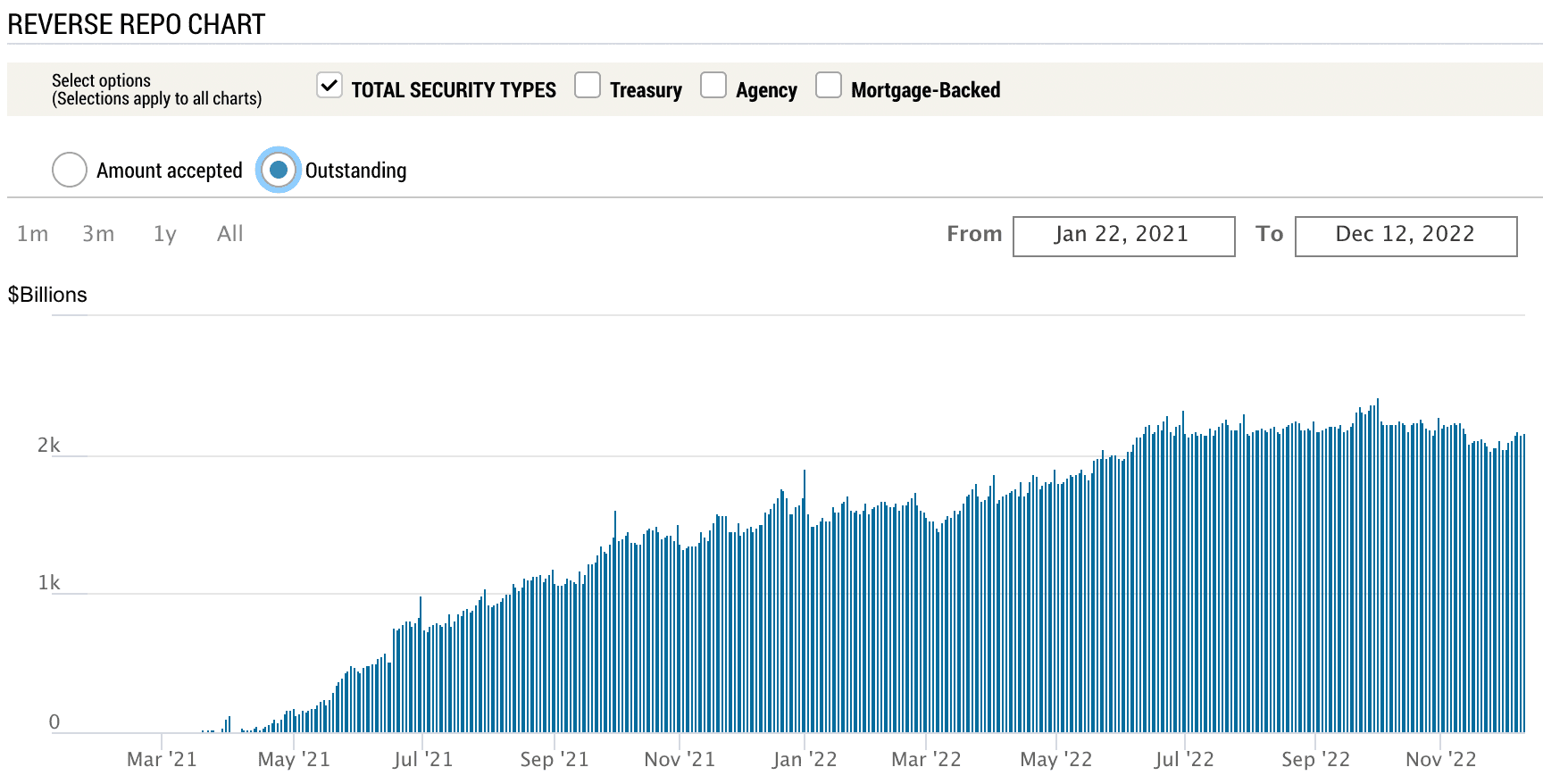

It is tempting to think that a problem is more likely to occur when the dollar is strengthening against other currencies, which until October was the position. This assumes that foreign bank and non-banks were net short of the dollar. But the rising trend for the currency is more likely to be evidence of net long positions. It is possible that this market will be threatened by short-term liquidity dislocations. But surely, there is over $2 trillion of reverse repo liquidity on tap…

The dollar liquidity position

There is excess liquidity in the US financial system. But the question is, why is it there and will it become available to resolve liquidity issues in the event of an FX crisis?

The Fed’s chart above of reverse repurchase agreements (reverse repos, or RRPs) shows that RRPs stand at $2.16 trillion. In an RRP, the Fed temporarily borrows cash using securities on its balance sheet as collateral, agreeing to reverse the transaction for an overnight return currently set at 3.35%, about 0.4% below its current fund rate (Note: these rates were before the FOMC raised the funds rate by 0.5% yesterday). A wide range of counterparties—primary dealers, banks, money market mutual funds, and government sponsored enterprises—are eligible to participate in the Fed’s RRP facility.

The Fed sets the overnight RRP rate to provide a floor under money market rates consistent with its Fed funds rate target, which has now been raised to 4.25%—4.5%. A counterparty’s decision whether to lend credit to the Fed at its overnight rate has little to do directly with overall market liquidity, but it is true to say that so long as there is substantial liquidity in the Fed’s RRPs, a repo blow-up, such as that witnessed on 17 September 2019 when on a credit shortage the repo rate soared to 10% is unlikely to happen.

It might appear to be a simple matter for the Fed to refuse to roll over RRPs to push liquidity back into the commercial banking system. But that is not how it works. To achieve that objective, the Fed would have to reduce its RRP rate to discourage rollovers, thereby ensuring extra liquidity is returned to the commercial banks. Not only are commercial banks reluctant to take large deposits on board because of Basel 3 net stable funding penalties, but to reduce the RRP rate goes against maintaining current interest rate policies. [Note that Basel 3 regards large deposits as providing a significant risk to bank balance sheets liquidity, while small deposits are seen to be a stable source of funding. Undoubtedly, this is why G-SIBs like JPMorgan Chase are now promoting retail banking services.]

Therefore, that over $2 trillion in large deposits has effectively migrated out of bank credit onto the Fed’s balance sheet is evidence of bank credit contraction. As well as complying with Basel 3, being aware of escalating financial and lending risks commercial banks are trying to reduce their overall credit exposure. Liquidating financial assets and refusing to extend loans to desperate borrowers deals with risks the asset side of a bank’s balance sheet. The entire commercial banking network cannot so easily reduce its obligations to depositors, necessary if banks are to reduce leverage on their collective balance sheets. Therefore, the reason liquidity is parked at the Fed in the form of RRPs simply reflects commercial banking reluctance to retain large deposits and is a counterpart to their reduction of balance sheet assets.

So much for the domestic dollar market. But as Borio’s BIS paper points out, the Fed has almost little or no intelligence concerning foreign dollar FX obligations and where the weak points might be. But it is not only a matter of dollar liquidity that might upset the money-market applecart. Each dollar transaction is matched by a foreign currency transaction, likely to be part of a chain. Very few FX transactions do not involve the dollar, because of the way the market works. An importer in India of Chinese goods has to sell rupees to buy dollars, and then sells the dollars for yuan to pay for the goods. In this simple chain, the counterparties are the importer, the importer’s bank, the exporter’s bank, and the exporter. In a deepening global recession, there’s much that can go wrong.

The BIS’s FX statistics only capture one side of a transaction, which is off-balance sheet, when double entries should reveal at least a doubling of the BIS’s estimates across all market participants. And a contraction in this outsized derivative market, driven by rising interest rate trends, is likely to expose liquidity problems in a maze of foreign shadow banks as well.

Europe’s liquidity position

In a marked difference from the US RRPs’ parking of over $2 trillion in short-term liquidity, according to the International Capital Markets Association Europe is also heavily dependent on repos for managing market liquidity. In a repo, an originating bank uses securities (usually government or high-quality corporate bonds) as collateral against cash. It is the other side of a reverse repo, which is how the other party would view it.

Repos and reverse repos have been a growing feature of interbank markets. In the past, daily excesses and deficiencies on deposits were negotiated in money markets through interbank rates, involving smaller amounts for agreements that were not collateralised. There were always individual credit limits for these transactions which limited their scope. For this and other reasons which need not detain us, repos became an increasing feature of money markets. What is more to the point is repos are conducted between commercial banks and the euro system because they set the overall level of market liquidity.

According to the last annual survey by the International Capital Market Association conducted in December 2021, at that time the size of the European repo market (including sterling, dollar, and other currencies conducted in European financial centres) stood at a record of €9,198 billion equivalent.[iv] This was based on responses from a sample of only 57 institutions, including banks, so the true size of the market is somewhat larger. Measured by cash currency analysis, the euro share was 56.9% (€5,234bn).

It allows European pension and insurance funds to finance geared bond positions through liability driven investment schemes — that’s what nearly crashed UK pension funds recently when it went wrong. This is fine, until the values of the bonds held as collateral fall, and cash calls are then made. This is unlikely to be a problem restricted to the UK and sterling markets.

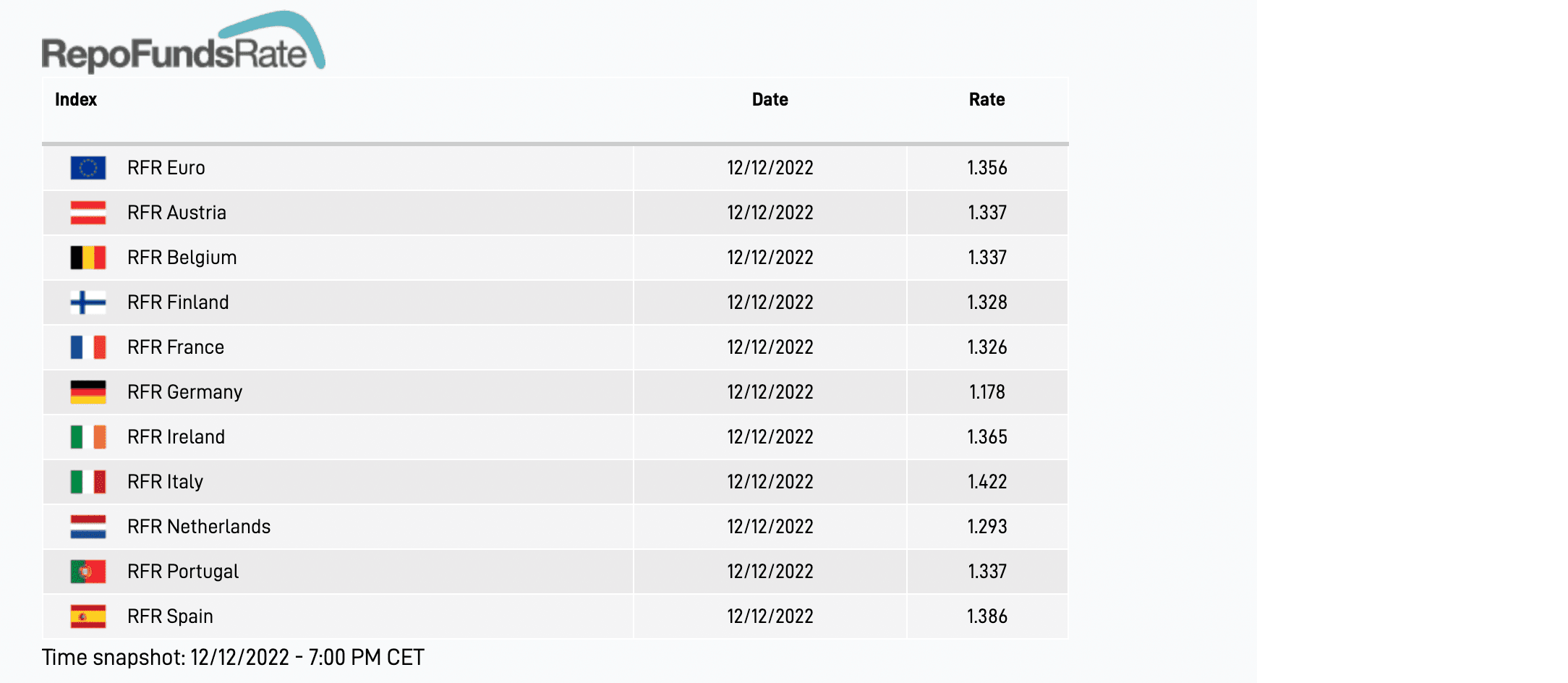

The common explanation is that quantitative easing has led to substantial quantities of high-quality collateral being absorbed by the euro system of the ECB and national central banks, leaving the commercial banking network as a whole short of good collateral and long of liquidity. Consequently, repo rates have been driven lower than the ECB’s marginal lending facility of 2.25% (i.e. its repo rate) as the table below from MTS Markets shows, as collateral is said to be more valuable to commercial banks than cash.

The analysis that suggests a lack of collateral is driving reverse repos between the euro system and commercial banks is only valid to a point. Liquidity is required by some banks to resolve temporary liquidity issues on an interbank basis by using repos for which they require collateral. But otherwise, the desire to park cash at the ECB and the national central banks appears to be similar to issues facing American commercial banks in their attempt to reduce the deposit side of their balance sheets. It is the banking cohort’s demand to dispose of cash that suppresses the repo rate.

Unwinding commodity derivatives

A far smaller OTC subset is commodity contracts, which by last June were recorded at $2.962 trillion. Classified by commodity, $820bn was in gold, $106bn in other precious metals, and $2,036bn in other commodities. While the June total is up 20% from the total at the 2021-year end, liquidity in underlying physical commodities is falling. This is particularly acute in metals such as silver and energy.

For bank trading departments, dealing in commodity derivatives has been very profitable, and despite the penalties with respect to Basel 3’s net stable funding ratio for balance sheet liquidity, banks have maintained exposure to this business. They usually take the short side, while speculators take out long positions. The price effect is that banks and their market makers create artificial supply to absorb investment demand, thereby suppressing prices below where they would otherwise be. Suppressed commodity prices feed into fiat currency stability, which is why western governments led by America have condoned the expansion of this inherently speculative business.

But the lack of underlying commodity liquidity combined with a trend of rising interest rates now threatens to increase derivative risk as banks turn from chasing profits to become more cautious. These commodity positions are not trivial either. The BIS figure for gold alone amounts to the equivalent of 14,170 tonnes at today’s prices, nearly four times annual mining output.

Additional to the OTC market is regulated futures and options totalling over $38 trillion (September 2022) which are backstopped by bank credit expansion. While positions in OTC derivatives are assumed to provide an offset to regulated futures exposure, in practice they can add to total short positions in marketable commodities such as gold.

Malinvestments in the non-financial economy

The example of unidentified risks in FX markets identified by the BIS is just one of several potential accidents in the banking and financial sectors of the global economy, which is unaccustomed to a rising interest rate environment. We must now turn our attention to non-financial entities, which have taken advantage of suppressed interest rates and easy credit to finance projects which would otherwise have been deemed to be unprofitable. Additionally, there will be many businesses which have struggled to survive even with artificially low borrowing costs, the zombie corporations.

The dangers to the global economy from these malinvestments were mounting even before the covid lockdowns, during which their costs then continued without any income from customers. Persistent supply chain disruptions added considerably to these businesses’ debts. And now, over-leveraged banks are trying to rein in debt obligations as rising interest rates threaten to bankrupt these entities.

It is tempting to think that governments can lean on commercial banks not to make a deteriorating situation even worse. And there is no doubt, that with government guarantees banks will want to cooperate rather than face debt write-offs and public reproach for their role in not extending credit. But it is not just a banking problem. Collateralised loan obligations have been acquired by many banks in lieu of direct loan exposure to corporate debt. And an additional horror is likely to be the unwinding of the private equity industry.

According to McKinsey’s 2022 Annual Review of Private Markets, by mid-2021 global private markets had grown to $9.6 trillion. There are a number of categories across a range of activities, but the basic theme is the same. A private equity partnership is able to raise funds at a lower cost than independent cash-generating businesses. It applies that ability to acquire control of the business and to leverage its balance sheet with debt, so that its return on equity is enhanced. Obviously, this strategy is driven by both suppressed interest rates and a continuing trend for them to remain low.

Those conditions have gone. Already, there are signs that this industry is running into difficulties. On 7 December, the Financial Times reported that Blackstone’s $69bn Real Estate Income Trust was limiting withdrawals from wealthy investors. The fund is twice leveraged, with $125bn of assets. The following day, Bloomberg reported withdrawals from Blackstone’s $50bn private credit fund. Both these funds are leaders in the US leveraged private market.

The mood music around lending to non-financials has certainly changed. And as far as can be seen, the consequences are hardly appreciated by the financial media – yet.

Conclusions

Even at this early stage of a new trend of rising interest rates, strains in the global banking system are becoming apparent. Bank balance sheets are as overleveraged as they have ever been particularly in Europe and Japan. And with rising interest rates ensuring a bear market in financial assets and widespread exposure to malinvestments leading to non-performing loans, banker sentiment is swinging firmly towards risk containment.

Money supply figures, which are showing a slowing down in the rate of credit expansion, only tell some of the story. Commercial banks in the US and the EU are using reverse repos to jettison liquidity on the deposit side of their balance sheets, to keep pace with the drive to reduce the asset side of their balance sheets.

Acting like the canary in a coal mine, we can already see derivative liquidity drying up in regulated gold and silver futures. This is probably being replicated in other commodity markets as well. But a far larger issue is FX crosses, swaps and forwards, whose notional values are not properly reflected on bank balance sheets, just one side of counterparty exposure being more than double the combined global systemically important banks total capitalisation of roughly $40 trillion.

As with all credit contractions, when and where the system will break is virtually impossible to predict. But when it happens, the crisis will be sudden. We must hope that the year-end financial window-dressing season passes without incident.

[i] See https://www.goldmoney.com/research/the-great-unwind-1

[ii] ibid

[iii]See https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2212h.htm

[iv] See ICMA Survey Number 41, published November 2021.