The Monetary roller-coaster of the 1890s in post-imperial Brazil

The Republic of Brazil in the 1890s tasted two opposite monetary systems.

By Bernardo Decoster

In the chaotic political upheaval after the fall of the Brazilian emperor in 1889 and the proclamation of the Republic in november, two schools of monetary policy clashed to control the Ministério da Fazenda (Ministry of Finance). The Metalistas, those who supported a “metal” based monetary system—that is, a gold standard—and the papelistas, those who supported a “paper” based monetary system—that is, fiat money. During the next 10 years, the Brazilian economy would taste both systems, providing a unique experiment complete with lessons in monetary policy.

Historical background

The Imperial Banking Reform of November 24th 1888 sought to deal with the effects of slavery’s abolition, signed in May of the same year, and the integration of newly-freed labour into the economy. As argued by the papelistas, the masses of newly-freed men would drive upwards the demand for money, putting a strain on the availability of the réis currency, urging a necessary expansion, guided by the Government, of its supply. On the other hand, the metalists urged a return to the esteemed exchange rate of 1846, during Brazil’s first experience with the Gold Standard, warning about the downsides of a rapid depreciation of the currency’s value should such an expansion occur. The Bill sought a compromise, with the final project having numerous inconsistencies and a net “zero reforms” (Franco 2014, in: Abreu).

The Papelista takeover and the encilhamento crisis

The military’s coup in November 1889 effectively expelled the Royal Familiy from Brazil, installing a transitional government to spearhead deep reforms towards a democratic republic. Named for the First Republic’s Ministry of Finance was Rui Barbosa, a notorious legal expert and classical liberal writer. Mere months later, in the January 17th decree (which was converted into Law), Rui placed full confidence in the papelista cause by elevating to “unavoidable necessity” (Ministério da Fazenda, Relatório, 1891, vol. I, p. 211) the expansion of credit at all costs, in order to fund the country’s industrialization and quench the thirsty demand for more currency. Barbosa looked to the American National Bank system for inspiration, dividing the nation into regions which operated under fractional reserve banking, authorizing each bank to print up to double its reserves (Franco 2014, in: Abreu). By September, the supply had increased by 40%, and an immense speculative bubble had formed in the stock market, with countless “artificial” companies constituted to take advantage of cheap credit.

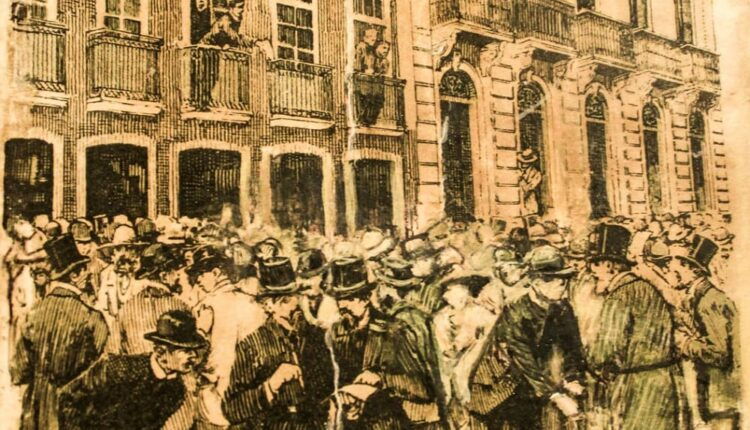

Around October, the government raised the minimum limit of capital needed to constitute a company, which temporarily “calmed nerves”, but in December 7th, Rui Barbosa ordered the unification of the banking system into a single central bank, authorized to print thrice its reserves. By June 1891, the supply had increased 80% compared to November. Barbosa left in early 1891, substituted by Araripe and, afterward, the Baron of Lucena, whose administrations were characterized by inaction. Like the Austrian Business Cycle Theory would predict, the credit bubble boom, inevitably, exploded, and soon came the bust. Nicknamed by the populace as the encilhamento crisis (named after the action of tightening a horse’s leash), it was the most severe economic downturn of the century.

The following months were marked by a severe inflationary crisis, with the value of réis halving in less than 10 months, causing a capital flight and the bankruptcy en masse of Brazilian firms, especially the behemoths of the railway industry. Whilst in November 1889 the exchange rate was 27 pence per thousand réis, in 1892 that value reached 8 pence per thousand réis, representing a more than 337% decline in its value in 2 years time. Amidst desperation, the public deficit reached record levels and navy revolts brewed in the South during the year of 1893, representing the climax of the crisis.

The Rothchild intervention: Murtinho leads the Metalista counteroffensive

The crisis continued until Prudente de Morais was elected president in 1894, installing Rodrigues de Alves in the Ministry of Finance. Both men sought the help of the Rothchilds, which agreed to £7.5 million in loans. Rapidly consumed, the Government faced difficulties stabilizing its accounts, barely making ends meet until February 1898, when both parties met to discuss refinancing the loan. The so-called funding scheme (as it became known in the Brazilian Government) designed by the Rothchilds imposed severe spending and printing controls on the Government, demanding an austere standing and the payment of the gigantic external debt contracted during previous years, waving off fears of a default.

As Joaquim Murtinho, a leading metalista, became the head of the Ministry of Finance in 1898, the Republic returned to a Gold Standard, and religiously followed the funding scheme. Such importance was given that, during following years, the budget was separated into the “gold budget” to pay for the scheme’s obligations, and the “paper budget”, for standard Government service provision. Murtinho sought to end what he considered “excess emissions” of paper money and the “pseudo-abundance of capital”, also taking a “let perish” stance on artificial companies formed during the bubble, blocking any bailout attempts. The bitter remedy for the crisis was, according to Murtinho, a hardcore austere stance and the strict adherence to the Gold Standard.

The Golden Age of 1900-1913

The exchange rate improved slightly, returning to 12 pence per thousand réis in 1902, but never reaching the esteemed 1846 goal of 27 pence per thousand réis. Under the metalistas, Brazil prospered tremendously, with the national product growing an impressive 4% per annum, with capital accumulation at an even bigger rate. In 1906, the convertibility to Gold was opened to the public at large and foreign investors, signaling a victory over the papelistas. Industries blossomed throughout the country, and living standards improved rapidly, with huge flows of foreign investments financing entrepreneurial activity until the Great War. Its impacts would dry out investments, causing a Government reaction of closing down the convertibility to gold, and once again return to the papelista mindset of spending and money-printing.

Source

FRANCO, G. A Primeira Década Republicana. In: A Ordem do Progresso. São Paulo: Elsevier Brasil, 2015.

INSTITUTE OF APPLIED ECONOMIC RESEARCH. História – Encilhamento: crise financeira e República. Available at: <https://www.ipea.gov.br/desafios/index.php?option=com_content&id=2490%3Acatid%3D28>.

A fascinating tale of a lost opportunity. Much like the mother country of Portugal, two rival factions, and generally the ‘worse’ side prevailed. Once again the long shadow of the Great War enabling destructionism. When it comes to inflation, it’s fair to say that Brazil can say ‘Hold my cerveja’ to most countries.

At least the names of the sides showed that they all knew what they were doing and what was at stake, the first step to any recovery. In Portugal as late as the early 1980s, there were paper 20 escudo notes circulating saying ‘Vinte escudos ouro’ meaning ‘Twenty gold escudos’, showing the vestigial memory of gold.